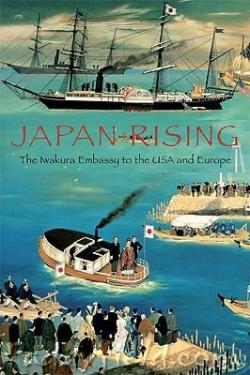

Japan Rising: The Iwakura Embassy to the USA and Europe

Cambridge University Press, 2009, 528 pages

Review by Roger Buckley

The grandest of grand tours made it back home without losing anyone en route. Despite rain in Manchester, snow in the Rockies, donkey rides in Egypt and hellish music in Shanghai the inspection team lived to tell the tale.

Yet this was no all-expenses-paid, fun trip for casual tourists. From late December 1871 until September 1873 a huge collection of Japanese politicians, officials and students under the charge of Foreign Minister Prince Tomomi Iwakura set out to examine everything and everybody across the globe.

The results of their survey of constitutions, counting houses and customs make for fascinating reading. If you want to know what an earlier Japan, just beginning to find its feet in the wider world of high imperialism, thought of the streets of Naples (“tunnel-like”) or the behaviour of Hungarians (“semi-civilized”) or the contrasts between Americans (“open initially”) and Brits (“they gradually thaw”), this is an ideal starting point.

Professors Tsuzuki and Young have shrunk the five volumes of the English translation originally put out by Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Japan (FCCJ) member Sumio Saito’s “The Japan Documents Enterprise” in 2000 into a more manageable 528 pages. The result sparkles with astute commentary, cross-cultural comparisons and views of both the post-Civil War U.S. (then comprising 37 states) and Europe that may not rank with de Tocqueville but remain of considerable value today.

Pride of place should go to Kunitake Kume, the young author of the undertaking. It was his task to look, record and then write up the Iwakura mission’s findings for a domestic audience. He obviously approached his orders with due diligence and loads of diplomatic tact – the reader never hears of anyone missing their train or nodding off during the interminable banquets and speeches that followed everywhere from the initial landing in San Francisco to the final days in Shanghai. Ambassador Iwakura’s opinions remain unstated throughout in what is very much a group report. It’s always a case of “we toured the palace,” “we were skeptical,” and “we were even given pickled herrings to eat, which were disgusting.”

Kume’s work provides a historical sketch of each country visited. This is then followed by notes on VIPs met, factories visited, parades watched and an analysis of the political, religious and industrial structures of the countries encountered. It is a careful, if often too generous, interpretation of the West and its Asian territories with the aim of better understanding the nations that had forced the unequal treaties on Japan in the early 1850s.

The mission saw at first hand the strengths and weaknesses of its counterparts abroad. Obviously, as Kume insists on emphasizing, the study tour did not always have time to dig under the surface, but the envoys do return home with an experience that can only be described as enlightening.

They are able to meet prime ministers, presidents and princes, take the pulse of the great powers and draw parallels between Japan’s predicament and those of emerging states in Europe.

Perhaps the two most revealing meditations take place in London and Berlin. When visiting the collections within the British Museum, Kume senses the gradual evolution of civilizations and feels that “we move forward by degrees. This is what is called ‘progress.'” He then criticizes his own country for having little comparable to what he has just seen displayed and adds that “to excuse ourselves by saying that we are of a different habit of mind is not an honest argument.”

A more practical lesson follows in March 1873 when the envoys have dinner with Bismarck in Berlin. The great man lectures them on his version of international relations, warning Japan to be wary of the British and French. Drawing on the experiences of Prussia when it also was “weak and poor,” he urges his audience to learn from Prussia in its quest for sovereign rights. Bismarck ends his pitch with a plea for German-Japanese friendship and warns the mission never to “relax your vigilance.”

Anyone curious about late-19th-century Boston or Amsterdam or Rome as seen through the eyes of an astute observer will enjoy Japan Rising. The fact though that its conscientious author lived on until 1931 is a reminder of how things would change. In the decades after the Iwakura mission, Japan too would soon join the ranks of the imperialist powers and bid to create its own new world order.