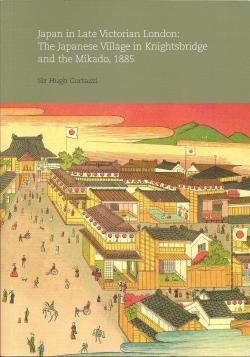

Japan in Late Victorian London: The Japanese Native Village in Knightsbridge and The Mikado, 1885

Sainsbury Institute, 2009, 100 pages including 16 plates, 12 illustrations, bibliography and index, ISBN: 0-9545921-1-5

Review by Sean Curtin

The idea that in 1885 there was a Japanese village located in Knightsbridge, the heart of bustling Victorian London, may strike many as being something more suited to a fanciful Doctor Who plot than a genuinely real fact. Thanks to Sir Hugh Cortazzi this long forgotten episode in the nascent years of Anglo-Japanese relations is brought bursting back to life in this excellently researched and beautifully illustrated book. Utilizing a wide variety of sources, he sets the context and describes the process which transformed a corner of Victorian London into “The Japanese Native Village, erected and peopled exclusively by natives of Japan (page 9).” In the 1880s there was an amazing thirst for “things Japanese” as the land of the rising sun represented an exciting and mysterious destination at the far frontiers of European knowledge and imagination. Recreating a Japanese village in fashionable Knightsbridge was just one way to satisfy the intense Japan-mania of the day and it also helps explain why in the same year Gilbert and Sullivan’s popular comic opera The Mikado was launched on the London stage for its first performances.

The village attracted large crowds and a massive amount of press attention with its replica Japanese houses populated by genuine Japanese men, women and children as well as its “magnificently decorated and illuminated Buddhist temple.” One of the projects most striking and crowd-pulling features was the presence of a considerable number of Japanese artisans and their families, which greatly enhanced the experience for the Victorian visitor.

Sir Hugh examines his subject from multiple angles, in one section looking at Japanese anxiety in Tokyo about how the Village might affect the image of Japan in Britain. Regarding press coverage he observes, “There was often a condescending tone to their comments, reflecting Victorian feelings of superiority to non-European peoples, and some gave way to the temptation to make fun of the Japanese and their ‘grotesque’ ways. But they were not generally unkind (page 14).”

The author manages to bring the village to life by profiling some of the figures most closely associated with the venture, especially the colourful and oddly named proprietor Tannaker Buhicrosan. In fact, chapter three of the book is devoted to Tannaker and his equally unusually named wife Otakesan Buhicrosan. Tannaker, who liked to be called Frank, appears to be the product of a union between a Dutch national and a Japanese woman from Nagasaki. Tannaker travelled extensively, with Sir Hugh unearthing reports of his visits to Australia and New Zealand and documents about his visits to Germany and extensive tours of England. From the fragments we have he appears to be a self-confident, energetic and highly successful entrepreneur. However, we have a very incomplete picture of him and his wife, Sir Hugh notes, “It is difficult if not impossible to find reliable accounts of them by people – friends or associates – who knew them directly, and so the picture we have of them has to be put together using information from census records, birth, death and marriage certificates and miscellaneous newspaper articles, making it necessarily patchy and sometimes contradictory (page 49).”

The Village was not the only Japan-related attraction to capture the public imagination in 1885, which also saw the popular Mikado hit the London stage. Sir Hugh observes, “The coincidence of the two events (the opening of the Native Village and of The Mikado) inspired reporters of the time to make a connection (page 61).” However, the author demonstrates that the two were not directly related remarking, “The Japanese Village opened in January 1885 only two months before The Mikado opened at the Savoy Theatre in March that year. Gilbert had begun work on the libretto of The Mikado long before that, in May 1884, and had in fact finished Act 1 two months before the Japanese Village opened. The inspiration for the opera is much more likely to have lain in the widespread fascination for things Japanese (page 63).” Nevertheless, there was a fair amount of crossover, London was not such a big city in Victorian times, and folks from the Japanese village assisted in various aspects of the stage production. Indeed, the programme of The Mikado in 1885 actually carried an acknowledgement of the support received from the Japanese Village, “The Management desires to acknowledge the valuable assistance afforded by the Directors and Native Inhabitants of the Japanese Village, Knightsbridge (page 60).”

1885 spawned two large scale Japan-enthusiasm inspired productions, one is amazingly still popular today, the other, until this illuminating book, long forgotten. The 1880s was a boom time for interest in Japan, in this superbly researched and brilliantly illustrated volume Sir Hugh Cortazzi resurrects the decade’s sense of raw excitement and sheer wonder about Japan. It was this energy and intense curiosity that contributed to the founding of the Japan Society in 1891, an organization which today still enthusiastically promotes and celebrates Anglo-Japanese relations.