Like Father Like Son

Directed by Hirokazu Koreeda

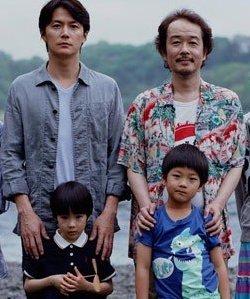

Starring Masaharu Fukuyama, Yōko Maki, Jun Kunimura, Machiko Ono, Kirin Kiki, Isao Natsuyagi, Lily Franky, Jun Fubuki and Megumi Morisaki

2013, 2 hours 10 minutes

Review by Susan Meehan

In his latest film, Kore-eda has once again excelled in exploring the inexhaustible theme of family focusing on a largely unstudied and fresh concern. He stretches it and prods the question of nature vs nurture as far as it will extend.

When six year old Keita Nonomiya starts taking all sorts of exams to enter primary school, a blood test reveals that he is not actually Ryota and Midori’s son. The news that they have the wrong baby comes as a devastating shock to the couple, though Ryota coolly says that it all makes sense now. What does he mean? Would Keita be a more musical child and a better fit for their stylish Tokyo flat if he shared Ryota’s genes? The accompanying music is full of foreboding and one cannot but feel anxiety for the families involved. It is a troubling, heart-wrenching scene.

Ryota Nonomiya, played by Masaharu Fukuyama, is a dedicated, hard-working architect. He tells his boss that he will make sure that this unexpected family complication won’t affect his work. He deals with the situation as if it were one of the ‘missions’ he regularly sets Keita to single-mindedly accomplish or overcome.

Ryota seemingly has no qualms in choosing blood over the beautiful, well-behaved boy he has nurtured with his wife, but Midori (Machika Ono) is reluctant to let go of a child she has raised for six years.

The Saikis, the family who have been raising Ryusei, the Nonomiyas’ genetic son, live outside Tokyo. The cheerful, scatty father works in an electrical shop and his wife sells bento, ‘packed lunches’. They are a warm couple with three children.

The complications and emotional difficulties are innumerable. It is difficult not to make judgments about the two different families. Which set would make the better parents? Who would be the most fun? Is fun as important as the provision of opportunities and music lessons? Is it fair to remove a child from siblings? How much of what children pick up is due to environment and familial ways, and will their characters change when the six year olds join other families? There are many shades of grey.

The child actors are all superb. In an interview given by Kore-eda on 12 October 2013 at the British Film Institute, Southbank Centre he revealed that he chooses the children for who they are at the audition and encourages them to act and talk as they normally would. During the filming process Kore-eda, influenced by Ken Loach, doesn’t give the children scripts. Instead he supplies them with background information about the individual scenes and prompts with suggestions.

The issues raised by the film are poignant and resonate, lingering in the mind for a long time afterwards. It is a most thoughtful piece of film-making, very different in style from Kore-eda’s recent I Wish (‘Kiseki’; 2011), but tackling difficult issues as he did in Nobody Knows (‘Dare mo Shiranai, 2004’) in which a parent’s abandonment of her children is the main theme. Kore-eda is one of the great exponents of children and their inner lives, unobtrusive like a David Attenborough in the wild.

Which father will Keita and Ryota turn into as adults? And, conversely, what influence will their boys have on the real fathers? What kind of father’s imprint will Keita and Ryusei be left with? The film leaves us pondering these uncertain conclusions.

Special After-Screening talk with Hirokazu Kore-eda at the BFI, Southbank Centre – Saturday 12 October 2013

At a special interview with Hirokazu Kore-eda, Jasper Sharp, writer and film curator, introduced him as a consistently innovative director.

His newest film, Like Father Like Son (‘Soshite Chichi ni Naru’) opened in September in Japan and quickly became the country’s top-grossing film of the year. Hollywood is looking into a remake.

Sharp asked Kore-eda why he thought his film had done better in Japan than this year’s Hollywood summer blockbusters.

Kore-eda suggested that it was because it features Masaharu Fukuyama, an artist and musician who is and has been very popular in Japan; because the film won a prize at Cannes and because the theme, about family, is close to everyone’s heart.

As to whether the film has a factual basis, Kore-eda said that in the 1970s in Japan there were quite a few cases of babies who were swapped at birth – and that he had done considerable research into this theme. In the cases of 40 years ago, children invariably went back to their blood families.

Sharp suggested that whereas Kore-eda’s film Nobody Knows (2004) is about lack of parental control, Like Father Like Son depicts what happens when there is too much parental control.

Kore-eda hadn’t previously thought of this. During the ten intervening years from having made Nobody Knows to Like Father Like Son, Kore-eda said that he had lost his mother and had a daughter and that these changes in his life’s circumstances may have attributed to the contrasting focuses of the films.

Sharp wondered how Kore-eda obtained such naturalistic performances from his young actors. Kore-eda said that for the last ten years he hasn’t used scripts with his younger actors but has them improvise on set. He helps by talking to them beforehand and whispering the context of the scene to be filmed.

He also becomes aware of the language the young actors use themselves and tries to incorporate this and their natural behaviour into the films.

During the casting of actors for Like Father Like Son Kore-eda recounted that one of the young boys said nothing other than, ‘Why?’ and ‘Oh my God!” Kore-eda used this exact language in the film.

Sharp pointed out that at one point Kore-eda had wanted to be a novelist. Kore-eda said that indeed he had gone to university with the idea of becoming an author but soon discovered that university wouldn’t prepare him for that. He spent all his five years of university in the cinema.

Sharp asked about Kore-eda’s friendship with the late critic Donald Richie. Kore-eda went on to say that Richie had been a great supporter and that their relationship went beyond that of filmmaker and critic. Richie would write back to Kore-eda about each of his films and always included a handwritten personal note. Kore-eda treasures these letters.

Kore-eda also mentioned the critic Tony Rayns and how he values and is interested in what Rayns says. While most critics made references to Yasujiro Ozu when reviewing Kore-eda’s Still Walking, Tony Rayns compared it to a Mike Leigh film, which Kore-eda valued.

Kore-eda was grateful for these relationships, and said that while he doesn’t make films for ciritcs, he appreciates an objective assessment of his work.

In the Question and Answer session with the audience, Kore-eda said that he is still hoping to made a film of Ri Koran, a Manchurian-born actress of Japanese decent who was launched into stardom during the Second World War as a “Chinese” singer and star of Japanese propaganda films.

Asked what films or directors have influenced him, he said that in his student days he watched and was influenced by Fellini’s La Strada and Nights of Cabiria.

He also admires Ken Loach and the naturalistic performances he achieves with his own young actors. Kore-eda admitted to having copied some of Loach’s techniques. While he sometimes is compared to the great master Ozu well-known for his studio-films, Kore-eda suggested that he probably owes more to filmmakers operating outside the studio system such as Loach.

Asked about the music in his films, Kore-eda said that he tends to choose an instrument per film. If it is a kids’ film he is likely to use a ukulele. In order to build atmosphere he will rely on an accordion. In the film I Wish, which is about trains and centred on kids, his motif of kids running was best accompanied with rock music and for that he got the band Quruli on board.