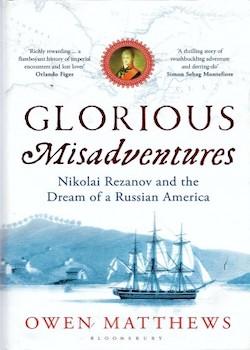

Glorious Misadventures: Nikolai Rezanov and the Dream of a Russian America

By Owen Matthews

Bloomsbury Paperbacks, Reprint edition

31 July 2014, 400 pages

ISBN-10: 1408833999

ISBN-13: 978-1408833995

Review by Sir Hugh Cortazzi

This well researched and well written book traces the career of Nikolai Rezanov who sought to establish and develop Russian settlements in North America from Alaska to modern day California. It covers his early life in St Petersburg from his birth in 1763, his involvement with the Russian America company, his travels in the Pacific and ends with his death in Krasnoyarsk in Siberia in 1807.

Rezanov was ambitious but he had a difficult and quarrelsome character and was often his own worst enemy. He was accompanied by the naturalist Georg Heinrich von Langsdorff whose lengthy account was published in 1813. Captain Adam Johann von Krusenstern, who commanded the ship on which Rezanov travelled on his main voyages, but with whom he was often not on speaking terms, also published in 1813 an account of his voyages with Rezanov.

Owen Mathews gives an interesting account of life in St Petersburg, in Siberia and in what was Russian America at the beginning of the nineteenth century, including Rezanov’s stay in San Francisco in which he, then a widower, became betrothed to Conchita, the daughter of the Spanish governor. Rezanov died before he was able to marry her and her story has provided a romantic subject for American and other writers.

The main interest for anyone involved in the study of Japanese history and Japan’s reopening to the west lies in the chapters devoted to the mission to Japan led by Rezanov in 1804/5.

After a tempestuous voyage from Kamchatka, during which the presents from the Czar to the Japanese Emperor were damaged by sea water and buffeting and Rezanov and Krusenstern quarrelled fiercely, the Russian ship, Nadezhda, arrived off the port of Nagasaki at the end of September 1804.

Rezanov’s visit was based on an over-optimistic interpretation of the letter, known as ‘the Nagasaki Permit,’ given by the Japanese to Adam Laxman eleven years earlier. This provided permission for a single Russian ship to come to Japan and trade. On this flimsy basis and on the humanitarian pretext of returning five shipwrecked Japanese, Rezanov vainly hoped to persuade the Japanese to open up to trade with the west.

Rezanov had no real knowledge of how Japan was governed in the Edo period and even less understanding of Japanese bureaucracy. He could not begin to comprehend the way in which the minds of the officials whom he met worked. He could not speak any Japanese and mistranslations and misunderstandings proliferated.

Owen Mathews relates the frustrations caused by official obstruction and deliberate delaying tactics. The Russians were forced to remain on their ships for weeks and even when permitted to land were confined in what was little bigger than a cattle pen hidden behind screens. The excuse of the local officials for the delays was that they had to consult the Bakufu in Edo. Because of the slowness of land and sea communications at this time instructions from Edo could not reach Nagasaki for months.

Rezanov did not help his case. He openly pissed into the sea in front of Japanese officials and constantly behaved in an arrogant manner. He often lost his temper and his personal hygiene shocked the Japanese. Krusenstern and Langsdorff were frequently disgusted by his behaviour and there were times when it seemed that Rezanov was losing his reason.

The response from Edo, when it finally came through and was conveyed to Rezanov, was a humiliating rebuff. At the residence of the Nagasaki bugyo (governor) Rezanov was handed, in what was described by the Japanese as ‘an extraordinary instance of favour,’ a handsome scroll. This declared that ‘Japan has no great wants and therefore has little occasions for foreign productions. Her few real wants…are richly supplied by the Dutch and the Chinese…’ The Shogun regretted that he could not accept Czar Alexander’s gifts or even his letter. ‘The basic laws of Japan forbid us from making foreign acquaintances.’

Rezanov was not allowed to pay for the food and other supplies, which had been provided by the Nagasaki authorities, and was told that Russian ships would not be permitted to return shipwrecked Japanese sailors. The Czar’s presents, which had been landed and rejected, had to be repacked and taken away.

On 5 April 1805 the Russian ship was towed out to sea and when out of cannon shot the ship’s powder and the crew’s swords and muskets, which had been impounded while the ship was in port, were returned to the Russians. The Japanese parting gift was ‘a beautifully – wrapped packet of seed for the Empress of Russia so that she might have Japanese flowers in her northern gardens.’