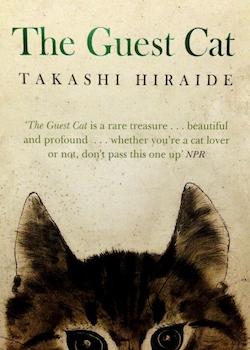

The Guest Cat

By Takashi Hiraide

Picador

25 Sept. 2014, 144 pages

ISBN-10: 1447279409

Review by Chris Corker

Takashi Hiraide, now in his mid-sixties, is one of the foremost post-war poets in Japan. He has won a litany of awards and released works covering an array of different genres and forms. The Guest Cat, considered to be both autobiographical and surrealist, won the Kiyama Shohei Literary Award in 2001.

Having read novellas by poets before and becoming accustomed to their rich imagery, I was surprised to find the prose in The Guest Cat bare and clinical. The pace of the book is lethargic, leaving the narrative to meander a little too often. Whether or not this lethargy is the appeal that saw The Guest Cat reach both The New York Times and The Sunday Times best seller lists, I couldn’t say. Perhaps some readers were enticed by the understated but beautiful cover and the papyrus-like paper. After reading, I was left with the feeling that nothing had really happened and, had the characters or the story developed at all, they had done so only infinitesimally. With certain authors, such as Flaubert or Wilde, a certain lack of content can be forgiven in light of their artistry with words, but it is hard to defend a story that says very little without that beauty.

Living with his wife in a quiet suburb of Tokyo, a writer is working hard to realise his ambition of becoming a full-time poet. The book opens with a description of a view through a window, highlighting the monotony of the protagonist’s protracted days. The couple live a slow, almost separate life; they say little to each other beyond the necessary. One day their chemistry is altered by the appearance of a beautiful young kitten they name ‘Chibi’ (roughly meaning small child in Japanese). Chibi gives the couple a common topic to discuss and a child-surrogate to fawn over. At all times, however, it is clear that Chibi is the neighbours’ cat, and her visits are accompanied with a sense of loss. Highlighting the Japanese notion of self and other, insiders and outsiders, the story discusses ideas of ownership and the selfishness this brings.

‘If the issue involved permission, then would things have been different if permission had been given? After all, a cat left outside on its own will cross any border it wants[…] Why do they hate us so much for taking care of Chibi?’

The idea of transient company – of transient love, even – is so entrenched in Japanese society that several businesses have been set up around the idea. Starting with Maid Cafes and Hostess Bars, where the focus is not sex but rather companionship, there are now cafes where patrons can instead be with cats and dogs, as well as other domestic animals. The proliferation of dating simulators is yet another indicator of this trend. As technology simultaneously connects and isolates the modern world, human loneliness provides a demand that businesses have recognised, offering fleeting remedies for a premium. In The Guest Cat, whether due to a lack of financial stability or simply out of preference, the couple are childless and never mention the possibility of having a baby. Their unlooked-for solution to loneliness and isolation is Chibi. This remedy, like Chibi herself, is ethereal and bound to end in heartache.

There are meditative moments in The Guest Cat that promise profundity, but often they are centred on dry subjects like geometry or the housing market and the tone is one more suitable for a lecture than a piece of prose. There are references to figures in antiquity which poets are traditionally fond of, but again this only adds to a feeling of academic sterility. Throughout, there is also an attempt at a Zen, nature-driven wisdom, but the book never really reaches those heights nor offers much aside from that failed aspiration. The themes of the fragility of life and loneliness are intriguing, but the way they are discussed is neither fresh nor particularly interesting; neither does the narrator or supporting cast have very much to say. I remember reading a review of Murakami’s recent novel Colourless Tsukuru, in which the reviewer questioned the wisdom of having a dull central character. I feel the same question could be asked here.

On a positive note, there is an obvious appeal here for the cat-lover, despite Chibi’s appearances being brief. Having grown up with cats myself, there were certain descriptions that were nostalgically familiar and Chibi’s assumed role as muse and child makes her by far the most intriguing character of the book.

There’s no denying that at times The Guest Cat has the pleasant, laconic pace of a Sunday afternoon. A Sunday afternoon, however, is valued only in its position at the end of an active week, as a needed respite. Here the eventful contents of the week are absent. I found in The Guest Cat the reality of an endless chain of Sundays, and for the first time I eagerly awaited Monday.