Global Baby Factory

Directed by Suzuki Atsuto

Translated by Rui Sayaka

RADA Studios, London

1 September 2016

Review by Susan Meehan

Global Baby Factory was performed at RADA Studios in London on 1 September, just days after the Indian Government approved the draft Surrogacy (Regulation) Bill*, which severely restricts the practice of surrogacy in India. This made Suzuki Atsuto’s original and thought-provoking theme also searingly topical.

37-year old university friends Sunako and Nachi are working out in a gym in Tokyo, bonding as they lament growing old without a love interest. Trim and youthful Sunako is paying huge amounts of money for a range of beauty treatments and products in order to preserve her youth, but won’t tell Nachi. And she’s leaving nothing to chance; as a back-up she has also frozen some of her eggs.

Sunako’s life is far from stress-free, however. Her parents are desperate for her to marry and have children. Her insensitive mother warns Sunako that she is no Cinderella and that her menopause is probably fast approaching.

Before long, Sunako reluctantly attends an arranged marriage party and falls for Jun’ichi. They soon marry.

In one of many hilarious scenes, a Greek-style chorus celebrates Sunako’s impending nuptials while also bemoaning Nachi’s single state, exhorting her to wed.

A calamity, befitting a Greek tragedy, strikes. Diagnosed with cervical cancer, Sunako, while still hoping for a baby, needs a hysterectomy.

The play shifts intermittently to the Desai Surrogacy Clinic in India, where potential surrogate mothers – most of them destitute housewives and cotton pickers – are paid 30,000 rupees each month while pregnant and an extra 300,000 rupees if the pregnancy is successful. This is enough for most of them to buy their own home.

The play concludes in India as Sunako and Jun’ichi travel over to collect their baby. Unexpectedly, they bump into Nachi who is in India on journalistic work, hoping to interview the Japanese couple she has heard about, who are having a baby via an Indian surrogate mother. The penny drops, Nachi realises the couple are her friends and she asks to interview Sunako on camera. Sunako refuses. She clashes with Nachi.

Is surrogacy exploitative? If not, why is it rife in India but not in Japan? Why didn’t Sunako’s sister take on the role of surrogate mother? Sunako feels she is giving her Indian surrogate mother hope and enabling material comfort. In Nachi’s words, is Sunako really using an abnormal system to become what she considers “normal”?

The play is far from didactic and allows the audience to ponder these themes for themselves.

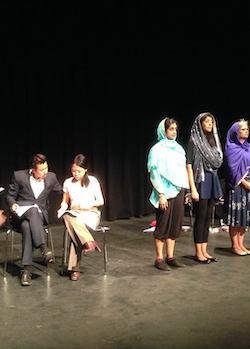

The casting was spectacularly good and, as with the previous play-reading of Suzuki’s The Bite, the Yellow Earth Theatre actors were fantastic. It was clear that they had devoted time and effort to familiarise themselves with the script and characters, the end product being virtually indistinguishable from a play in the way it was performed. Kumiko Mendl’s flawless direction seems to have perfectly captured the essence of Suzuki’s play. The flamboyant chorus scenes were cleverly directed and acted and other surreal scenes, involving the shortlisting of surrogate mothers and the release of sperm to name a couple, were funny and memorable.

Q+A

The Q+A with Atsuto Suzuki following the play-reading was facilitated by Takekawa Junko, Senior Cultural Officer at the Japan Foundation. She began by remarking that it was rare for a male playwright to deal with issues of infertility.

Suzuki pointed out that there was a personal reason for this. He had been in a serious relationship with a woman 12 years his senior, and they had begun to talk about having children. As he was 32 and she was 44, they confided in a friend who worked at a fertility clinic and who was able to give them advice. Suzuki admitted to not having been aware until that point of a woman’s biological clock.

He was then inspired to write the play in 2012 after finishing a book called Justice by the philosopher Michael Sandel which references the surrogacy industry in India. The play was first performed in 2014, and was well-received in Japan.

Suzuki has since written and staged Global Baby Factory 2 which was instigated by the story of a very rich Japanese man who arranged for 20 of his babies to be born to surrogate mothers in Thailand.

Takekawa then referred to the fact that Suzuki often writes about taboo or touchy issues (such as eating dolphin in The Bite) and wondered whether he intentionally writes with a view to reflect contemporary Japan.

Suzuki replied saying that he doesn’t consciously attempt to convey contemporary or controversial topics. He continued by saying that in Japan audiences like plays with small casts and which delve deep into certain situations. In order to appeal to this predilection writers in Japan tend to write plays which focus on family or friends. Suzuki has a different approach. He likes writing about encounters between people from different cultures and enjoys including non-Japanese in his plays as it has become less rare to come across international people in Japan and he wants to reflect this aspect of contemporary Japanese society.

Suzuki said that during his time in the UK he met a gay couple who had a baby via a surrogate mother. This encounter has inspired him to want to write Global Baby Factory 3.

Quizzed about his views on surrogacy, Suzuki said that before visiting India, once he had completed the play’s first draft, he was not convinced that it was a good idea. He visited a dwelling near the fertility clinic housing surrogate mothers, all of whom seemed quite happy. One of the pregnant women told him that she was carrying a Japanese baby. At that point it dawned on Suzuki that a regulated form of surrogacy is probably better than a black market system. He is still unsure, however, about the merits and demerits of surrogacy.

Asked whether there are any religious or moral pressures in Japan against surrogacy as there are in the UK (e.g., the Church) Suzuki said that there isn’t really any overall religious pressure. Individuals would face family or peer pressure above anything else.

Sticking to the theme of peer and parental pressure, Suzuki pointed out that plenty of women like Sunako exist in Japan, pushed by their parents into marriage and into having children. Nevertheless, the birth rate in Japan is still very low pointed out Takekawa, and she suggested that this topic could form the basis of another play!

*The draft Surrogacy (Regulation) Bill ‘provides for surrogacy as an option to parents who have been married for five years, can’t naturally have children, lack access to other reproductive technologies, want biological children and can find a willing participant among their relatives.’ The bill ‘would also restrict overseas Indians, foreigners, unmarried couples, homosexuals, and live-in couples from entering into a surrogacy arrangement. The surrogate mother has to be a married woman who has herself borne a child and is neither a non-resident Indian (NRI) nor a foreigner. Couples who already have biological or adopted children cannot commission a surrogate child.’ (‘Understanding India’s Complex Commercial Surrogacy Debate, India’s draft Surrogacy (Regulation) Bill sparks debate over the government’s role in reproduction,’ by Ibu Sanjeeb Garg in The Diplomat, August 31 2016)

Yellow Earth theatre company was formed in 1995 with the aim of developing the range of acting opportunities available to British East Asian actors. In March this year, it celebrated 21 years of theatre making with an international play reading festival, Typhoon, at Soho Theatre and Rich Mix in London

This was part one of ‘Winds of Change: Staged Reading 2016’. The Japan Foundation, in collaboration with Yellow Earth and StoneCrabs Theatre Company present a new monthly series of events, to introduce UK audiences the work of some of Japan’s most outstanding playwrights, all of which will be heard in English for the first time.