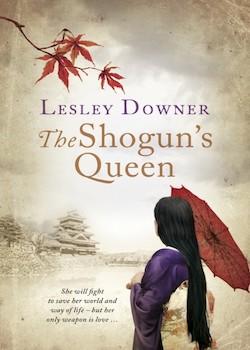

The Shogun’s Queen

By Lesley Downer

Bantam Press, 2016

ISBN-10: 0593066863

Review by Elizabeth Ingrams

The historical and emotional sweep of Lesley Downer’s The Shogun’s Queen takes your breath away. While some people may have filed Downer’s work under ‘Japanese romance’ or ‘geisha’, this book takes her tetralogy about the death throes of Japan’s Edo period (1603-1868) to new heights. The story of Atsu, also known as princess Sumiko or Atsuhime (the title of NHK’s major 2008 historical drama), is the stuff of legend. Elevated from her samurai origins in the Satsuma domain to be married into the Tokugawa family as a political match to one of Japan’s last shoguns, the epileptic Iesada (ruler from 1853-1858), Atsu’s rise and self-sacrifice is conceived as mirroring the sacrifice made by Edo-period Japan in the face of external forces.

It is 1853. Commodore Perry’s ‘black ships’ have arrived at Shimoda and Japan is now ruled by a very different shogun to the fearsome Tokugawa Ieyasu, who, along with his son, expelled foreigners in the 17th century. Now the Shogun has been warned that the West wants to force open Japan’s ports for trade, and as a terrifying precedent, China’s southern coast has been bombarded by the British to force the continuation of its opium trade. These threats require drastic measures and changes to the Shogun’s inward-looking administration. Lord Nariakara, lord of the Satsuma domain, sees opportunities in trade with the West, but also the dangers of an unequal partnership; in a bid to end 250 years of division between the house of Tokugawa and the ‘outlying’ lords of the Satsuma, Choshu and Tosa domains, Nariakara makes an unlikely match for his strong-willed niece Atsu.

Against this backdrop, and Nariakara’s ambition, Atsu, aged 15, is just a pawn. As the first test of her steel she is given a diplomatic letter to deliver to the previous lord of ‘crane’ castle in Kagoshima before making her way to Miyako to begin her adoption into the Imperial household (part of her process of becoming a princess, for the sake of becoming eligible to marry Iesada). Along the way she faces assault and abduction, but by far the greatest trials come only after she has become eligible for ascension into the gilded cage of Edo castle’s women’s palace. She is aware that this is effectively a one-way ticket to luxurious incarceration. The key secret that everyone has omitted to mention to her is that her husband-to-be is incapable of ruling.

From the beginning, Atsu conceives of Edo castle as a persimmon with a maggot at its centre: the maggot in this case is Lady Honju-in, her mother-in-law. She has more power than Rome’s Livia or Scotland’s Lady Macbeth having succeeded in obliterating all other rivals to the throne (including twenty-five children) in order to establish her sickly son, Iesada, as sole heir. The whole of Edo is held hostage to her power as she refuses to come to terms with the arrival of US Commodore Perry with his fleet of black ships, and what it means for Japan’s – and by extension her – position. Atsu’s mission, closely monitored by her lady-in-waiting, Ikushima, is to persuade Iesada to install a regent who can take decisions in his place, rally Japan’s lords ‘and to work out a solution to the impossible situation we are in.’

Her vain attempts at womanly diplomacy for the installation of Nariakara’s favourite as regent, go against Lady Honju-in’s preference for a 12-year-old heir, a decision which would plunge Japan ever closer to the civil war that Nariakara has been striving to avoid. However, along the way Atsu does succeed in driving her new husband, Iesada to overcome his inhibitions, resentment and epilepsy to make an impressively enigmatic peace agreement with the Americans: ‘Pleased with the letter sent with the Ambassador from a far distant territory and likewise pleased with his discourse – intercourse shall be continued forever.’

Downer depicts the halcyon final days of the Edo period with brilliant sympathy, as she has done in the previous novels, which are set a decade or so later. What brings this tale of female statecraft to life above all, is the dialogue. Downer has an unerring knack for capturing spiteful repartee filtered through silken politesse; in this courtly language, every act of humility is feigned and every put down is framed as concern for the feelings of the other. The real danger for Atsu comes once Iesada has died, poisoned, it is suspected, for striking a deal with Perry. Only at this point do we see a fall from grace; the high-class choreography plummets into farce as Lady Honju-in accuses Atsu of plotting against her son. She picks up her imperial kimono only to descend on her young opponent: ‘You were in it too, you miserable interloper,’ she screeches, ‘you wormed your way in here, fooled us with your pretty face and pretty ways. I should denounce you too.’

As we learn in the afterword, Atsu’s intransigent loyalty to the shogunate paid off, leading her ultimately to negotiate a peaceful surrender of Edo castle to the imperial troops in 1868, ushering in the Meiji Period. In the triumphant culmination to her tetralogy, Downer succeeds in lifting noble Japanese samurai women from the dust of a period when, according to the prevailing Confucian diktat, women had ‘no place outside the home’. She gives life to Atsu’s brave struggle to save their country from destruction, and in doing so, does a great service of providing inspiration not only for Japanese – who in my humble opinion are in desperate need of strong female role models – but for readers of all nationalities. I only fear that if Hollywood were to lay their hands on the rights to this tale the true elegance, sophistication and moral courage of a character like Atsu would be lost in the more obvious commercial selling points of political intrigue, Japanese swagger, assassination and hara-kiri, all rolled together as the curtain rises on the arrival of America to the stage of her first major Pacific ‘subaltern’ alliance.

Elizabeth Ingrams is the author of Japan Through Writers’ Eyes, Eland Publishing Ltd, 2015, ISBN 978-190601108-6