The Citi Exhibition Manga マンガ

The British Museum

(23 May-26 August 2019)

Review by Malene Wagner

As I set off to explore British Museum’s Citi exhibition Manga マンガ , I am puzzled by my first encounter: the very British 19th-century heroine, Alice. Is she there to reassure me that all is not totally unknown and mad in this other kind of Wonderland that is manga?

Luckily, I quickly find myself in the company of some very Japanese heroes such as Astro Boy, Monkey D. Luffy (leader of the Straw Hat Pirates) and Pikachu. And I bump into a range of Japanese monsters, ghosts and goblins peeking out from the dimly lit gallery who strangely reassures me that I am in fact no longer ‘at home’.

Although still considered somewhat foreign and exotic by many of us in the West, some aspects of Japanese culture have been adopted into mainstream Western culture – just think of sushi, sake and sakura. With this exhibition, the largest one on manga held outside of Japan to date, British Museum shows that manga too has a place in modern-day Western (pop) culture.

But what is manga exactly?

Some people will associate manga with Hokusai (1760-1849), Japan’s most famous artist whose Great Wave has become a global icon beyond its Japanese roots. It was with Hokusai that the term manga was made widely known when he used it for the title of his drawing manual in fourteen volumes, Hokusai manga (北斎漫画), published from 1814 onwards. The meaning of manga in that context was ‘random drawings’ or ‘pictures run riot’ reflecting the content of the books’ weird and wonderful scenes of daily life, nature and animals, the supernatural and not least humans often depicted with a humoristic twist.

But, to many others, manga (マンガ) are modern-day comic books or graphic novels, read by both children and adults, with subjects ranging from adventure to comedy, to drama, to horror, to mystery, to romance, to science fiction and sports, even erotica, and the list goes on. There really is, as one headline in the exhibition states, “A manga for everyone”.

That is not to say that the two kinds of manga are not related – they are! Both a visual narrative art form, they are historically and artistically connected; one could argue with roots going back to the 12th-century Handscrolls of Froclicking Animals (Choju giga), displayed as a later copy in the exhibition.

The focus of the exhibition is manga as the contemporary story-telling. We learn how to both read and draw manga and we are introduced to how manga is produced in Japan today. A mock-up of the oldest manga bookshop in Tokyo (which closed only in March this year) invites us into the everyday-life of manga consumers as we can enter the ‘shop’ and read classics like Princess Knight or 1980s Dragonball or maybe one prefers Oda Eiichiro’s One Piece, which broke the Guiness Book of World Records for the most copies sold for the same title by a single author.

The exhibition truly feels like a contemporary manga universe. But we are reminded of its links to Edo-period ukiyo-e (woodblock prints) and Meiji-era magazine illustrations by examples throughout the exhibition acting as an undercurrent to the modern-day manga. And although it is tempting to compare the two, the classic ‘masterpieces’ are best seen as context for the contemporary manga drawings, not a literal equal.

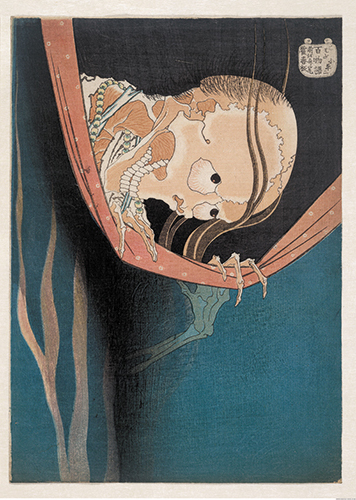

One example, is one of Hokusai’s best works, the skeletal ghost Kohada Koheji, part of the series Hyaku monogatari (One Hundred Ghost Tales) from c. 1833. Rather than making a one-to-one visual comparison, one can appreciate the influence of the comic and grotesque Edo-period ukiyo-e on today’s manga.

Colour woodblock, 1833.

© The Trustees of the British Museum

A highlight and truly unique piece of the exhibition also manifests the historical undercurrent: a 17 x 4 metres big theatre curtain painted by pupil Kawanabe Kyosai (1831-1889) in 1880 for the Shintomiza theatre. The curtain features scary and ghosts and demons – a returning theme in Kyosai’s art works – but they are in fact popular kabuki actors of the time, identifiable by facial characteristics and their family crests (mon) featured above each figure.

Another father of manga is Tezuka Osamu (1928-1989) with his hero Astro Boy, known in Japan as Mighty Atom. The story of Astro Boy was first featured in the monthly magazine Shonen in 1952 (and continued until 1968). Since then, Astro Boy has grown into an icon and he has become one of the faces of Japan’s ‘soft power’ policy. For the Tokyo Olympics 2020, he will act as one of the official ambassadors. He is proof that manga is more than just entertainment but also an integral part of Japanese culture, on both a national and a global scale.

This exhibition seeks to tell the story of modern manga, from its origins in late 19th-century Japan to its role as a global phenomenon in today’s culture.

For the British Museum to take up a pop culture theme like manga is refreshing. It would have been easy to make an exhibition focusing on the great ukiyo-e masters of Japanese art and only referencing contemporary manga in the passing. Instead British Museum has done the opposite and sheds light on a pop culture phenomenon that has moved beyond its Japanese roots and ‘role models’.

Manga is a mad world. But in no way too frightening or foreign. It’s really about not taking it too seriously and just letting yourself fall down that rabbit hole (in true British style).

Manga マンガ opened at the British Museum on 23 May and will run until 26 August. Accompanying the exhibition is the publication Manga edited by Matsuba Ryoko and Nicole Coolidge Rousmaniere, the main curators of the exhibition with Uchida Hiromi. It is published by Thames & Hudson in collaboration with the British Museum.

onwards

©Satoru Noda / SHUEISHA