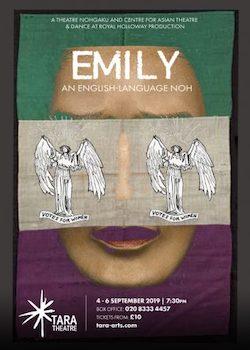

Emily

Directed by Matsui Akira, Richard Emmert, Ashley Thorpe

Tara Theatre

(4-6 September 2019)

Review by Alice Baldock

There is a great deal of intelligence, attention to detail, and gratitude to theatrical tradition behind Emily, an English-language Noh play. A project that has began at Royal Holloway, home to the Handa Noh Stage, the only permanently-standing Noh stage outside of Japan. This rendition of the piece has been stripped down to fit the dimensions of the friendly Tara Theatre, to bring the project closer to central London.

The piece begins with an explanation by Ashley Thorpe. The audience jumps right back to the fourteenth century and then back to the present. The aim, here, is to take Noh and show that it can be relevant, and not just as a way of performing, kept alive by re-iterating the same pieces again and again. Instead, he proposes that Noh is relevant – both to contemporary times, and to places outside of Japan, where Noh as a practice was conceived. This is a bold claim to start with, as any claim to universal applicability is. Yet, with the weight of centuries of spectators and performers claiming Noh to be a ‘Japanese’ artform, it becomes all the bolder. There have been several attempts to produce Noh in English in the past. WB Yeats took a stab at it from 1914, but a script alone is not enough to produce a full Noh play; it needs a composer, needs to pay attention to use of space. Emily is one of the more successful English-language Noh plays. The creators (Ashley Thorpe, Richard Emmett, and Matsui Akira) have made something both original and faithful to the art form it draws inspiration from. Starting by making a plea for Emily’s relevance may be unconventional, but it immediately engages the audience to think about not only what they are watching, but why.

The audience is asked: should we consider Noh as drama? A long-standing, sometimes unacknowledged debate enters the heart of the theatre. Noh has a script, but it also has drama, dance, sound, song as essential elements. Looking at art forms from all places and all times is a gentle reminder either that our paradigms are so often narrow, or that we are desperate to place things into boxes like drama or dance or sound. Academia and performance tend to keep their distance from each other, and it is refreshing to see them brought so decidedly into conversation, even if this continues to raise more questions.

The performance itself is split into two. First, a rendition of Atsumori in Japanese, expertly performed by Matsui Akira. Following this, Emily. This is a story revolving around the death of suffragette Emily Wilding Davidson, who goes down in history for being the suffragette who threw herself in front of a horse in 1913. The first half seems to be a justification that the second is truly Noh, allowing unfamiliar audiences to see the parallels in performance style and content between the old and the new. This kind of structure is incredibly clever, proving a point whilst not transforming the evening, which is intended to be art, to descend into a lecture.

Emily proves itself in many ways to be faithful to the aspects it showcases in the first half. The quality of movement was exemplary from all performers. The very act of curling each toe down to graze the floor, the balance of one’s body weight whilst moving, the bodies swaying through space as if moved by the breath of the music that surrounded them. These were all constant throughout the night. They also fascinating to watch. Each performer moved with passion and sincerity.

Other aspects were cleverly incorporated. The story uses the structure of many other Noh pieces where a traveller figure, the audience’s medium into the Noh story-world, discovers a mysterious character. This character departs and returns latter to reveal themselves to be a non-human entity. In Emily, the traveller acts as our perspective, guiding us to uncover the unsettled spirit of the jockey who killed Emily, Herbert Jones. Emily’s creators prove that this structure does work for new stories, revealing new stories to the audience.

The problem at the heart of the story is one of gender, which the creators seem to have thoughtfully considered. It was the kyogen, or comic relief interlude, which interestingly brought these issues to a head. Two characters, both history students, debate the legacy around Emily with a mixture of academic debate and personal attack that perfectly mimics a university tutorial. The characters shout at each other, one is called ‘too much of a feminist’, the other denounced as a misogynist. Their side plot, seasoned with lashings of actual debate, was both informative and comic, especially amid the deliberately slow-moving pace of the rest of the play. It also was a good place to bring the questions around Emily forward without writing Emily into the play, a decision Ashley Thorpe took to avoid the difficulties around a male writer creating a female voice.

However, choosing such a topic, and using Noh to tackle it, does raise some questions. Women were banned from practicing Noh until the 20th century, and from becoming professionals until 1948. Those with female bodies still found themselves limited in what they can do as practitioners, and these limitations, though eroding, are doing so slowly. The essence of Emily seems so antithetical to this that it raises the question – why use Noh to tell this story?

Not only is Emily visually and aurally beautiful, it also makes clear arguments for Noh’s relevance to the contemporary world.