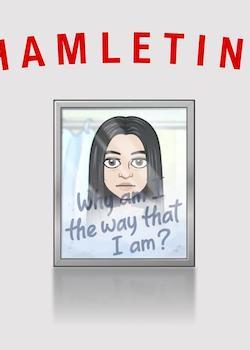

Hamletine

Directed by Bart Price and 2021

V&A

(29 August – 5 September 2019)

Review by Alice Baldock

In 1960s attendees of a trial over art and obscenity in Tokyo left court to find mysterious slips of paper scattered on the ground. The paper pointed them to a secret performance. Pamphlet-holders handed 500 yen to a disembodied, outstretched hand, which was exchanged for a beer and entry into the space. Those who tried to sneak in couldn’t gain entry to such an intimate space.

I can’t help but be reminded of this story when I arrive at the tunnel entrance to the V&A in London. Elusive instructions have guided me here, and I’m handed a pair of ear plugs. The audience is ushered into the space, the gaping underground entrance to a museum whose heritage seems in opposition to what I’m about to see. Once everyone is arranged, on a scattering of director-style stalls and cushions, in this vault-like place, the doors swing shut behind us. It is a moment of both exclusivity and confinement. No one else can get in, but there hangs, thick in the air as heavy metal doors slam shut, the realisation that no one can leave.

What begins then, is artwork that is not an art installation, drama, Hamlet-adaptation, reflection on hikkikomori, or an exploration of abject boredom. It is not-quite all of those things, and this not-quite-ness suits it very well. The action moves between projected moving image and a performance by Minna Gladstone. Music, deconstructed techno interspersed with more tender musical interludes, overwhelms everything. The audience is forced to put in their ear plugs, which then creates a sense of disconnect from every other viewer. The screen takes us through a series of images: plastic-pop-bright swimming pools and sunglasses, a girl filming herself posing with a teddy bear, a girl laying on a pebble beach. Meanwhile, on an inflatable mattress in the middle of the disoriented spectators, the girl on screen appears in real life, moving through her personal space as if she were utterly alone. The combination of sound, searing colour lighting up the dark tunnel, and her movements, which seem to be incredibly deliberate, is fascinating. Although there is no obvious narrative to pull the audience along, I find myself content to watch, wondering what she will happen next, even as these movements appear to be absurd, without meaning.

Three individuals worked on creating this piece, and each brings a different take on loneliness. There are parts where Minna seems merely bored. She eats a banana, slowly, peeling it from the bottom end. Once she is done with it, she considers it for a while, then places it on her head as she watches herself on-screen. At others, she turns her attention inwards to herself, and we see a human fascination with one’s own flesh body. At others still, the girl on screen is out in the world and deeply afraid. The outside world becomes a photo-negative of itself, pedestrians become demonic. This is where the concepts hikikomori and doomer memes start to come into the picture. Whilst not making a statement about hikikomori, it does seem to note that there are some aspects of being alive right now, particularly the ability to be connected to a sprawling online world, whilst you remain closed-off from human contact. The existence of hikikomori is a lynch pin connecting the creator’s experiences, the online world, and literature.

The connection with Hamlet is obvious to anyone who knows the plot of Hamlet, but it doesn’t really matter to those who don’t. The piece lacks words, a way of playing with Shakespeare that is rarely done in performances other than dance, considering it is language that we usually remember Shakespeare for. It is possible to watch Hamletine without knowing this, but the idea of being alone, alongside several vignettes connect the two pieces. Minna sprawls in a swimming pool, Ophelia-style. Even more telling is the mise en abyme we find everywhere: little avatars decorate the pillowcase and bed covers, and the audience watches Minna watch herself.

It is at this point when questions around spectatorship start to bother the audience. Minna poses at times almost nude, but in such a way that gently undermines, or engages in a dialogue with, the line between spectator and voyeur. She examines herself, unaware of or not caring about who is watching her. She also looks back, from the screen at the audience, challenging them to think about where and how they look.

Though not for the faint-hearted, Hamletine is a piece that can provoke a huge array of emotional and intellectual responses, drawing on a refreshing mixture of pop culture and canon literature to create something both overpowering and meditative.