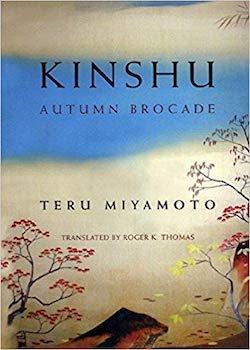

Kinshu: Autumn Brocade

By Miyamoto Teru

Translated by Roger Thomas

New Directions (2007)

ISBN-13: 978-0811216753

Review by Robert Paul Weston

When my wife spotted the review copy of Miyamoto Teru’s Kinshu on the bedside table, the book’s main title writ large, she assumed it was a treatise on alcoholism.

“You’re giving up drinking?” she asked me.

The problem was the final letter u—or lack thereof—in the word kinshu. Written without it, a native Japanese reader might assume the word is an English transposition of 禁酒, a prohibition on liquor—hardly ideal for a meditative novel on love, loss and karma. Indeed, Miyamoto’s original title was Kinshuu (錦繍), a multi-layered word for a fabric of beautiful embroidery; a similarly beautiful and varied poem; or a richly coloured mosaic of autumn leaves. Hence the elucidative English subtitle: Autumn Brocade.

The omitted u is no fault of the translator, Roger Thomas, who successfully rendered the story’s tender, conversational prose from Japanese. The severed u is more likely a victim of English’s orthography and aesthetics, in which doubled vowels appear clumsy, more like typos than examples of editorial assiduousness.

On the other hand, what’s in a name? What matters more is whether the novel lives up to its multi-layered title. I believe it does—and does so well—but I say so with certain reservations.

Kinshu is an epistolary novel, told in a series of letters between a divorced and thoroughly estranged couple. Aki and her former husband, Yasuaki, have neither spoken nor seen each other in over a decade. Aki’s opening letter describes a chance encounter on a gondola ascending Mount Zao in northern Honshu. Based on this mere sighting, Aki feels compelled to seek out Yasuaki’s address and write to him, searching for the truth about his sordid and bloody departure ten years earlier.

Aki’s opening letter tells how, only two years after marrying, the police telephoned her in the middle of the night. Her husband, they explain, has narrowly survived a suicide pact with another woman, a hostess from a Kyoto night club. The two were found in a hotel room near Arashiyama, the woman dead and Yasuaki clinging barely to life. Aki rushes to Kyoto and finds her husband in hospital, emerging from surgery following the treatment of stab wounds to his throat and chest.

The wounds are not found to be self-inflicted and, when he regains consciousness, Yasuaki confirms this. The woman attempted to murder him in his sleep, apparently in a fit of jealousy, although her full motives remain unknown. When he awakes, Yasuaki is gripped with shame, but also with wilful silence. After an infuriatingly spare apology, he walks out of Aki’s life with little more than the clothes on his back.

They will not see each other again for ten years, when the chance encounter on Mount Zao prompts Aki to begin the correspondence that forms the novel.

This dramatic opening is followed by a meandering meditation on fate, karma and the random chaos of the universe, yet always with reference to discrete memories of the everyday—a fondly remembered meal; the strictures of household finance; beautiful scenery viewed from a passing train; snatches of half-heard melodies; a subtle expression on the face of a mother or son. In this way, groping for links between the prosaic and the cosmic, Kinshu is a beautiful, melancholic, ultimately hopeful novel.

At the same time, however, the book’s representation of men and women—or rather, husbands and wives—could be a struggle for some. Miyamoto’s novel was first published nearly forty years ago, in 1982. Gender relations have moved on significantly since then. As a result, the portrayals of Aki and Yasuaki could come across as products of their time, more conservative than they might be today.

In particular, one of Yasuaki’s letters asserts his belief that men are somehow innately predisposed to adultery. Aki rejects this, but the notion that male infidelity is inevitable may grate on modern readers. That said, there is a kind of softly brutal frankness to these letters, written long after the couple’s irreparable rift. It gives both correspondents a gripping—if at time’s off-putting—authenticity.

Perhaps precisely because so much time has passed for the characters, as opposed to the reader, a structural mismatch occurs. I could not help wishing Yasuaki would simply show more compunction. Certainly, he apologises for the ruin he has made of the couple’s happiness, but when I imagined myself in his position, I only saw blinding, all-consuming guilt. Similarly, when I put myself in Aki’s place, I felt desperate fury. While she does express anger in her letters, she finds a surprisingly quick a path to a zen-like forgiveness.

By choosing to tell the tale by way of letters, Miyamoto has left much room for reflection on the part of his characters. The result is the description of events that, when fresh, would leave anyone furious, confused, shocked into despair. For the reader, the destruction of the characters’ marriage is fresh. The characters themselves, however, benefit from the salve of time. They describe their dramatic break, their anger and sadness, with quiet, wistful, almost lyrical prose.

The danger is this incongruity may alienate some readers as their anger butts against the characters’ subtle reflection. Or perhaps the incongruity has a pleasure of its own. Looking back on this review, I can see how the novel’s structure has deepened my thoughts about it, which is its own success. After all, so much of the novel is about precisely these things: Time and reflection. A multi-layered brocade indeed.

* Robert Paul Weston is the author of Sakura’s Cherry Blossoms.