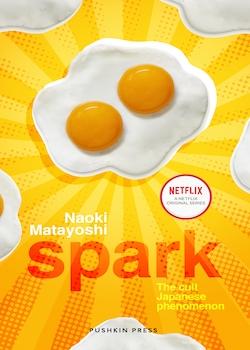

Spark

By Matayoshi Naoki

Translated by Alison Watts

Pushkin Press (2020)

ISBN-13: 978-1782275909

Review by Laurence Green

When the cover of a book quite literally bursts out at you in vivid, fluorescent orange – glistening fried eggs spewing out from the centre – it’s hard not to pay attention, even more so when said book is the recipient of Japan’s prestigious Akutagawa prize. Spark (in Japanese, hibana) proclaims itself the ‘cult Japanese phenomenon’, but truth be told, having sold more than three million copies in Japan, one could quibble about where to draw the line between cult success and bonafide blockbuster mega-hit. Either way, the sales figures are remarkable, and make for envious reading for UK booklovers for who such dizzying heights are almost never scaled here. Is this the sign of a Japanese reading public head-over heels with high-brow, prize-winning literature?

The answer lies in the book’s origins: comedian turned author Matayoshi Naoki. Famous as part of the comedy duo Peace (alongside partner Ayabe Yuji), he is also known for hisnumerous TV appearances, where he has a history of playing historical figures such as Natsume Soseki and Tokugawa Iesada. One might scoff at Matayoshi’s seemingly easy transition from comedy to books – it’s easy to draw parallels with similar celebrity successes here in the UK – but what is immediately apparent on sitting down with a copy of Spark is that this is no hastily bashed out cash-cow, but a serious bit of quality literature.

Akutagawa Prize winners of late have had a tendency to revel in oddball characters – think Murata Sayaka’s acclaimed Convenience Store Woman – and Matayoshi’s Spark is no exception. Very much a kind of autobiographical work, the story focuses on manzai comedian Tokunaga and his elder partner Kamiya, following the duo as they rise to success, whilst simultaneously portraying the nuances of the two men’s relationship with each-other. Neither is initially an attractive figure; they drink a lot, swear a lot, and in general act like a couple of guys up to no good. What fascinates most about Spark is how so much of the novel puts narrative drive aside and simply leans on this central relationship between the two men to propel it forward, a dynamic completely and utterly defined by the Japanese senpai (senior) / kohai (junior) bond. For all his faults, Tokunaga looks up to the crazed genius-like Kamiya, seeking his guidance and knowledge as the pair look to make their way through the fickle world of comedy.

This is a very ‘talky’ book, whether it be the constant, rapid-fire back-and-forths between the two main characters, or the more reflective introspective monologues, giving a window into Tokunaga’s morose view of the world. This is both a blessing and a curse, on one hand, this perfectly encapsulates the feel of manzai comedy (and this is, after all, a book fundamentally about comedy as a concept) but there is also a lingering notion that not all the jokes hit home as hard as they’d like. Readers with a sufficient knowledge of Japanese culture and language will have a clear sense of how certain passages would sound in Japanese, and that sometimes, they just don’t connect in quite the same way rephrased into English. Still, for the most part the translation by Alison Watts is of excellent quality and tonally, fits well with the other Japanese output published over the last few years by Pushkin Press.

So, while readers with less of an intimate knowledge of Japan might struggle a little, those primed with some cultural background will find plenty to love here, especially in the book’s detailed description of its primary setting, Tokyo’s trendy suburb Kichijoji. Against a backdrop of this eclectic hipster paradise, the book does a good job at visualising the intangible essence of comedy onto the page – it’s worth noting here though that the book has already been turned into a televised adaptation available on Netflix (something the front cover is also keen to advertise). One of the best jokes hangs on the simple but ridiculous wordplay inherent in the fact that to eat a hotpot could be taken as meaning either the foodstuff, or the pot itself. Humour like this thrives in the fabric of the humdrum actions and habits that form our lives, the moments that seen out of context, seem utterly banal. Spark excels as a comedy of the absurd, but it is an absurdity shot through with the constant struggle against melancholic everyday tedium. A Japanese Withnail & I, perhaps?

While so many books fall victim to ‘strong start, weak finish’ syndrome, Spark is immensely satisfying in that it grows into its strengths. By throwing us in at the deep end, we are forced to acclimatise slowly to the foibles of its characters, the world of Japanese comedy and the way our two leads co-exist with it. Because of this, when the book hits its stride in an exhilarating final third that sees one of their most impassioned performances play out in real time, it is all the more propulsive. Somehow, the exercise of transitioning the power of a stand-up routine onto the printed page works, and the punchy, breathless energy of the sequence works wonders.

And then there’s the stunning, and quite literal, revelation that comes in the book’s closing passages. To say any more would be to spoil the surprise, but it is a moment that once encountered, cannot be unread, and arguably transforms the reader’s entire relationship with Spark and its two main characters. Both emphasising and complicating a potentially homo-erotic reading of their relationship, one can question whether the sheer dominance this moment has over the rest of the book potentially cheapens it, or is simply the tour-de-force in a sequence of progressively more outlandish stunts the book pulls as part of its comedic arsenal. Suffice to say, said ‘reveal’ is what will stick in the minds of most readers first and foremost. As a remarkable punchline to an already strong final third, Spark reminds us here that sometimes it really is the most brazen comedy that can be the most effective at hammering home a point.

It all feels like a fine companion to 2018’s Pulitzer-winning Less by Andrew Sean Greer, another compact novel that was not only unafraid to portray the more emotional, fragile side of masculinity, but also to pair sharp humour with a kind of begrudging world-weariness. These narratives thrill because they feel so distinct from the kind of chiselled Hollywood heroes we are used to seeing on screen. In the pages of a book, these men are given room to ruminate in the depths of their thoughts, and it is testament to Matayoshi’s satirical skill that Spark feels like a ripe skewing of contemporary Japanese culture. Peel back the prim, pristine exterior, and there is a whole lot of messiness beneath.