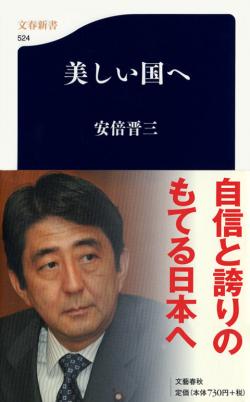

Utsukushii Kuni E (Toward a Beautiful Country)

By Shinzo Abe

Bunshun Shinso, Bungei Shunju (2006)

ISBN-13: 978-4166605248

Review by Fumiko Halloran

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, at 53 the youngest to hold that office in the post-war period, has written a revealing book about his life, political philosophy, and vision for a good society. The timing of its publication was impeccable as the book hit the stores just before he was elected to the premiership. The book, "Toward A Beautiful Country," swiftly rose on the bestseller lists.

In his preface, Mr. Abe divides political leaders into those who fight for what they believe and those who choose not to fight. He counts himself among the former. For him, fighting politicians take action for the people even if they are criticized, presumably by other politicians, opinion leaders, and the press. On the other hand, non-fighting politicians are those who may be agreeable on the surface but never take actions that would invite criticism.

He points to an episode in the pre-war British Parliament when Arthur Greenwood, a member of the Labour Party, questioned Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain who was seeking to appease the Nazi dictator, Adolf Hitler. Chamberlain's eloquence in answering Greenwood's questions almost stumped him but his colleagues shouted: "Arthur, speak for England!" Encouraged, Greenwood proceeded to give a powerful speech demanding that Britain go to war to stop Germany from its military aggression. Mr. Abe concludes that he wants to be a fighting politician who listens to the public saying "Speak for Japan."

Throughout the book, Mr. Abe goes back to British political history in which his hero is Britain's wartime leader, Prime Minister Winston Churchill. Abe discusses the difference between British and American liberals and defines himself as "conservative," adding that he wants to be a "conservative with open mind." Some American journalists have casually branded Mr. Abe as "right wing," which is not the same as "conservative." Had they read this book, they might have realized that Mr. Abe is a complicated person who examines issues from many angles.

From the time he was six years old, Mr. Abe grew up in a political environment that shaped his views. His grandfather, Prime Minister Nobusuke Kishi, was criticized by opponents of the revised US-Japan Security Treaty in 1960. Mr. Kishi was convinced that by revising the 1952 treaty, which limited Japan's rights, Japan would gain a more nearly equal position in its security relations with the US even as the treaty committed the US to defend Japan. Opponents of the revised treaty, however, sought to demonize Mr. Kishi as a villain. From this experience, Mr. Abe seems to have learned to distrust sweeping political passions. He particularly developed a distrust of the press that he sees as having its own political bias and agenda.

Mr. Abe is no stranger to international politics. His father, Shintaro Abe, was the foreign minister in the cabinets of Prime Minister Yasuhiro Nakasone from 1982 to 1987. In that role, Abe Sr. visited 39 foreign countries, taking Abe Jr along as his executive assistant 20 times. As Chief Cabinet Secretary in the Koizumi cabinet, Mr. Shinzo Abe made a strong impression on the public in foreign policy, such as statements on the North Korean kidnapping issue.

On issues such as the Yasukuni Shrine, economic sanctions against North Korea, revision of the constitution, and expanding the activities of the defense forces abroad, Mr. Abe pursues one theme, which is to establish Japan as a truly sovereign nation. He wants to lead a Japan that can assert its national interests in an equal relationship with other powers. He rejects, however, the stamp of narrow-minded nationalism and argues that one's love of country does not lead to excluding others.

On Yasukuni, Mr. Abe points out that prior to 1985, the Chinese government never criticized the visits by Prime Ministers Masayoshi Ohira, Zenko Suzuki or Yasuhiro Nakasone even though the names of Class A war criminals had been added to the registry at the shrine. After the Asahi Shimbun criticized Prime Minister Nakasone's visit in 1985, the Chinese government began its campaign of criticism. Mr. Abe refers to the Sino-Japanese Peace Treaty of 1978 that states the two countries agreed not to intervene into each other's domestic affairs. Obviously Mr. Abe believes that paying respects to the war dead is natural feeling for Japanese, making this a domestic issue. After his visit to China immediately after he was elected prime minister, the Chinese government has not brought up the Yasukuni issue. Even so, the issue will remain in the shadows as a potential threat for his foreign policy. Polls in Japan last year showed that a majority of Japanese supported Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi's visit to the shrine last August because they did not want him to cave in to the Chinese and Koreans. At the same time, they had complicated reactions to the issue of Class A war criminals. One argument was that it was not right to list the names of the war criminals because none had died in battle. Some were acquitted, others died before the verdict, and the rest were hanged. The Yasukuni issue has once again stirred debate about Japan's war responsibility among Japanese.

Mr. Abe spends considerable time on American foreign policy, starting with isolationism, Manifest Destiny, and the expansion of its military power in the 20th century. He cautions Japanese that their image of American Democrats as peace-oriented and Republicans as war-oriented is simple-minded and mistaken. He believes that regardless of party affiliation and different approaches, the American belief in maintaining superiority of their country is the same. For him, US-Japan alliance is vital not only for security but for shared values and beliefs in freedom, democracy, and a market economy.

Even with all this focus on foreign policy, Mr. Abe writes extensively on domestic issues including retirement and social security, aging, child bearing, education, and taxes. He wants to see a society that rewards those who work hard in a fair competition. He wants to see a Japan where the government protects its citizens, but encourages them to take initiative and not depend on the government. He wants to see a society that provides multiple opportunities. That may sound like an American dream but Mr. Abe's thinking is deeply rooted in Japanese history and cultural values.

What to make of him? He says he would be a fighting politician but would listen to the voice of the public. In this book, he goes to a considerable length to explain who he is and what his thinking is. Yet in recent polls, his approval rate has dropped from 70% at the outset to below 30% just prior to the catastrophic July 2007 Upper House election and even lower before his shock resignation in early September 2007. A major Japanese complaint was that he did not explain his thinking enough to show them where Japan was going. In contrast, Prime Minister Koizumi had a knack for sound bites on TV and never explained anything in detail, yet was very popular. Perhaps Mr. Abe's biggest challenge was his failure to capture the hearts of the Japanese public.

A different version of this review first appeared on the National Bureau of Asian Research (NBR) Japan-U.S. Discussion Forum and is reproduced with permission.