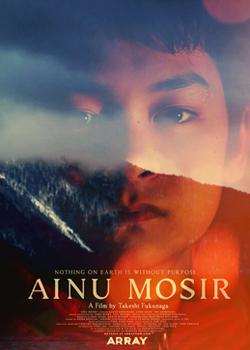

Ainu Mosir

Written and directed by Fukunaga Takeshi

Cast: Shimokura Kanto, Akibe Debo, Shimokura Emi, Oki, Yūki Kōji, Miura Tōko, Lily Franky

Available on Netflix (2020)

Review by Susan Meehan

Ainu Mosir is a sensitively filmed slice of contemporary Ainu life, as well as a rites-of-passage story set in Lake Akan Ainu Village in Kushiro City, Hokkaido. While not a documentary, it is a realistic portrayal of the community. The cast is comprised of locals, which accounts for the strong and convincing connections between the characters.

The Ainu, Hokkaido’s indigenous people (the Ainu population of Japan is currently around 25,000), faced repression and discrimination, and many Ainu customs were outlawed when Hokkaido was assimilated by mainland Japan in the latter half of the 19th century. The timing of the film is important. It wasn’t until 1997 that the Japanese government passed the Act on the Promotion of Ainu Culture, and as recently as 2019, the Japanese government passed a bill officially recognising the Ainu as an indigenous people of Japan [1]. Interest in all aspects of Ainu culture has visibly grown in recent years, and in July 2020, a national cultural facility, Upopoy, opened in Shiraoi, Hokkaido to promote Ainu culture and arts.

14-year-old Kanto is the film’s contemplative protagonist and his mother in the film is in fact, his mother in real life. Both use their real names in the film, Kanto and Emi.

As the film begins, the viewer is immediately immersed into the verdant and abundant nature in and around Akan, while also made aware of the Ainu Village’s economic reliance on tourism. We see a shot of beautiful Lake Akan and scenes with plentiful, crisp snow. In another scene we a shop abundantly stocked with Ainu-style wooden carvings, headbands, and instruments including the mukkuri (mouth harp). The main street in the Ainu Village is nothing but a strip of tourist shops.

Visitors from abroad and mainland Japan are shown to be captivated by the souvenirs for sale and crowd the shop where Kanto’s mother works. It is comical when a Japanese tourist compliments Emi on her spoken Japanese, causing her to smile and mischievously say she has been studying hard. The viewer is in on the joke having witnessed Kanto’s mother in class for beginners learning the Ainu language.[2] The tourists, happily buying into the tourist trap, are complicit in fomenting this double life.

While Emi and others in the village seem to wholeheartedly embrace their Ainu heritage, Kanto is torn – it’s the classic struggle between yearning for independence and the pressures of conformity and submission – not just within the familial context but within the community as well.

Kanto doesn’t feel that Akan is normal because he has to do Ainu things. His mother, on the other hand, sells Ainu craft and is eagerly asked by customers if she is Ainu – furthering and giving reason to her Ainu identity.

Even though he has not been brought up to speak the Ainu language, Kanto feels there is no escape from this oppressive Ainu-ness. His rock-band mates consider incorporating Ainu instruments to complement their electric guitars and a drum set, but Kanto resists wondering why everything they do needs to have an Ainu angle.

Enter Debo - a friend of Kanto’s recently deceased father. Debo takes his Ainu identity very seriously and more so than any of the elders in the village. They are reluctant to assert their identity to the extent of further “othering” themselves, thereby alienating the non-Ainu Japanese.

Debo gently tries to kindle Kanto’s interest in Ainu culture, and tasks him with caring for a very cute bear cub. This will be their secret. Kanto thrives on his clandestine visits to the cub - its confinement akin to Kanto’s feeling of claustrophobia.

Kanto continues to struggle with his feelings, engaging the viewer’s empathy. To what extent should traditions be forced on the younger generation, and what about traditions that are out of synch with modern life and modern beliefs? Is it healthy to live in a village which relies on its touristy theme-park image and sense of cultural difference to keep it afloat?

His eyes are opened to the inescapability of his background, as well as the richness that can be unearthed. His struggles are similar to those of second-generation migrants, though in his case his family have not even moved village. The struggles are also generational, adding to the universality of the film.

Perhaps the 2020 bill, which obliges the government to adopt policies to protect and support the cultural identity of the Ainu will help Kanto re-evaluate his inheritance and learn to esteem and reclaim it as his own. Promoting Ainu culture will only add to the richness and diversity of Japan, and redress the lack of attention it has tended to receive.

The film’s director, Takeshi Fukunaga, was born in Date, Hokkaido in 1982. Despite being raised in Hokkaido, he didn’t really become aware of the Ainu until moving to the United States in 2007 to major in film at City University of New York Brooklyn College.[3]

[1] ‘Japan's Ainu recognition bill: What does it mean for Hokkaido's indigenous people?’, The Japan Times, 25 February 2019.

[2] Though few speakers of the Ainu language exist, it seems to be undergoing something of a renaissance.

[3] Matsumoto Takuya, ‘To Know the Ainu Is to Know Japan: An Interview with “Ainu Mosir” Director Fukunaga Takeshi’, Nippon, 23 December 2020.