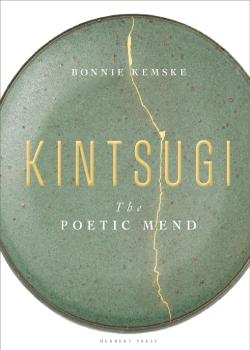

Kintsugi: The Poetic Mend

By Bonnie Kemske

Herbert Press (2021)

ISBN-13: 978-1912217991

Review by Eleonora Faina

Kintsugi: The Poetic Mend is a beautifully illustrated book where artist, Japanese tea ceremony student and author Bonnie Kemske guides us through the origins and techniques of kintsugi, a Japanese art form and repair method to restore broken objects using lacquer and gold. Born in Okinawa, raised in the US and currently living in England, Kemske gifts us with her second publication exploring kintsugi’s history, its metaphorical power and her encounters with artists and ceramist both in Japan and in the West.

Its 175 pages’ margins are connected by a golden line and it is immediately clear this book tells a story. The Daiwa Anglo-Japanese and Sasagawa Foundations sponsored the research trip Kemske took in 2019 to collect information and material for this book and I was lucky to be part of the homonymous webinar they hosted in late February 2021 which further ignited my interest in reviewing it.

The book is six chapters long, marked by their respective golden kanji: dives into kintsugi’s origins, different types of kintsugi repair, its contemporary use and different interpretations of its metaphor which proved to be pivotal in its popularity abroad. Images understandably are dominant, yet the text is substantial, beautifully accompanying pictures of kintsugi repairs, step-by-step technique demonstrations, meetings with artists and shots of the Japanese landscape and its physical cracks.

Kintsugi literally means “to join with gold” and it is a mid-16th, 17th century Japanese repairing lacquer technique. It accentuates the gold seems between joined pieces. A notion probably not so popular in the West, mending is seen as inherently important in Japanese culture: affirming the scars, the imperfections can turn the broken piece into something even more beautiful than its original form. The original piece is not just repaired but is an entirely new, unique, stronger art element. It tells a story of the past whilst drawing attention to the now.

The technique of joining broken pieces with metal originated in China but its most articulated and artistic form is certainly Japanese. The first examples of kintsugi in Japan can be traced back to 1500 BC during the Jomon era where black lacquer extracted from toxic urushi trees started to be employed. With the discovery of gold in 750 BC a fine powder was added on top of the lacquer, marking the advent of modern kintsugi.

The process is described as very time-consuming and requiring highly skilled artists to deliver the repaired piece in its enhanced beauty. Urushi trees only grow in East Asia; its secretions seasonally extracted are applied one layer at the time at specific temperatures, making its employment protract the repair for several months. It can be used with several materials like wood, lacquer, and glass but its best recognised form is pottery, specifically in chanoyu (tea ceremony).

It is really in the latter environment that kintsugi flourished as an aesthetic: chanoyu started to be considered as high art in the opulent Momoyama era (1573–1603) and its political and economic importance brought this maki-e (sprinkling gold power on urushi) originated technique to be associated with status and prestige in the Japanese society. Tea utensils were used as a reward to reinforce loyalty within strict hierarchies. Japanese concepts like wabi (accepting irregularities translated as humbleness and simplicity in one’s life), mottainai (do not waste, letting every object fulfil its function) and mono no aware (acceptance and appreciation of the impermanence of life) were pivotal in the establishment of kintsugi to this day.

Yet, Kemske reveals kintsugi constituted a “hidden art” in Japan; the artists, kintsugi-shi, have rarely been mentioned in the repairing documentation and this is mostly recognised as a “side-line job”. Many kintsugi-shi back in the Tokugawa era were essentially makie-shi who employed their lacquers skills. Only recently kintsugi artists are embracing this as a proper profession in and out Japan although gold repairs are still offered by the majority of makie-shi.

Why, then, this Japanese art form got such a grip in Western societies in recent years, spurring artistic interpretations by Page Bradley, Ono Yoko, Paul Scott, Claudia Clare and endless publications of self-help books based on its concept? That is, according to the author, because of the power of a good metaphor: a visual one that also entails transformation. It is often referred to ‘the art of resilience’ in the West [1] or accepting imperfection and irregularities as part of something natural. In Japan honouring the fractures, the process towards renewal is more aesthetically powerful than a brand new, perfect, possibly mass-produced item.

Not surprisingly, the book points out kintsugi is deeply related to earthquakes as people in Japan are accustomed to living with over 150,000 earthquakes per year. Its demand usually rises in their aftermath to remember lost ones or rebuild family tokens. Living with cracks and breaks is just natural and if anything, reinforces the precariousness and imperfection of the world we live in, stimulating a renewed appreciation for the beauty surrounding us.

I really enjoyed diving into this rich, weighty book. It is visually gorgeous, its selection of pictures exquisite and it taught me a great deal of kintsugi. I particularly appreciated the interviews and artists’ personal stories such as Raku Kichizaemon XV’s Nekowaride and the encounters with Suzuki Goro in Japan and John Domenico in the US. Each interpretation was different in style, size, concepts, and type of kintsugi used. Some of them broke items on purpose, some decided to turn into art a particularly unlucky pottery batch, others had their wives mending items of great sentimental value. Those are stories of redemption translating as lengthy, emotional projects.

Kemske’s description of her time in Japan were quite vivid too: in her narration of surroundings and encounters with the artists she manages to reproduce a specific sense of tranquillity, measured movements and Shintoist reverence towards the environment (houses, trees, ceramics, and quality of light). Japanese literature connoisseurs and those who have experienced the country first-hand will be able to really visualise her description and appreciate how authentic they feel.

The author also refers several times throughout her book to Westerns spreading incorrect info and using kintsugi “promiscuously”. Yet she recognises the beauty of kintsugi becoming more mainstream, largely more accessible, relevant, and exposed to audiences in different parts of the world. Timothy Toomey - UK coordinator of the Kintsugi Project and working at the Embassy of Japan in the UK - said in 2014 the aim of the project ‘is to stimulate an interest in kintsugi in the West, leading to a commercial interest which will help revive a craft in Japan that time and a changing way of life have caused to be in danger of disappearing’.[2]

The last chapter, dedicated to kintsugi’s symbolism opens with remarks of re-invention and renewal especially in the current pandemic’ climate. It could be argued living throughout a pandemic has been a shared metaphorically seismic experience that has reminded us of human frailty, the importance of reinventing ourselves and cherish what we have. It has triggered emotional and physical scars in each of us and the significance of kintsugi could be more relevant than ever nowadays. It encapsulates the renewed creativity, resilience, and innovation many of us had to turn to as a coping mechanism, transcending its purest art form. It also transcends the individual experience: companies like Forbes recognized it and NKD pointed out 'through the hardships we all weathered, the organisations who have been successful ‘instead of yearning for the old days have filled the gap created by the pandemic with something better’,[3] reinventing themselves.

The book is a testament of a narrative of loss and recovery, breakage and restoration, tragedy and ability to overcome it in respectful acceptance of loss and hardships. In her very last pages Kemske introduces the only ceramic bowl she ever made during a chanoyu class in Japan, over 30 years ago. The bowl broke shortly after, its remains kept away by an old friend of hers. Recently kintsugi repaired and delivered in conjunction with this publication, the bowl represents something much more meaningful that it would show at a first glance. It brings closure, it enriches loss and celebrates the past, encapsulating kintsugi’s metaphor perfectly.

As the drive to repair is universal so it is the drive towards catharsis: ‘a scar does not form on the dying. A scar means I survived’[4]. The gaps filled with gold represents the acceptance we need to exercise towards things not looking nor feeling like they used to. Learn how to heal our wounds and unapologetically reverence them might represents today’s ultimate art form.

Notes

[1] Serge Maillard, ‘“Kintsugi” or the art of resilience’, Europa Star, Editorial, May (2020).

[2] Quoted in Tony McNicol, ‘What is kintsugi?’, WedoJapan, 15 May (2014).

[3] Laura C, 'Coming out the other side of the coronavirus pandemic – not just stronger, but different', NDK (2021).

[4] Quoted in Kemske from Chris Cleave, The Other Hand (2008).

Book Discount

Kintsugi: The Poetic Mend is available on the Bloomsbury website with a 20% discount. To obtain the discount, use the code TJS20 when purchasing the book here (the discount code expires on 31 August 2021 and is valid in the UK only).