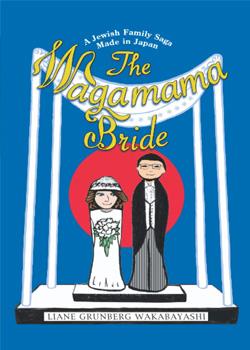

The Wagamama Bride: A Jewish Family Saga Made in Japan

By Liane Grunberg Wakabayashi

Goshen Books (2021)

ISBN-13: 978-0578844046

Review by Renae Lucas-Hall

This compelling and insightful memoir reads like a classic love story full of trials and tribulations. Liane Grunberg Wakabayashi’s spiritual journey in Japan from secular to orthodox Judaism is a reflection on transformation, relationships, family values, finding happiness, and being true to oneself.

Grunberg Wakabayashi moves from New York to Tokyo in 1987. This non-religious Jewish girl embraces the good life in the Land of the Rising Sun. She works as a copy editor at The Japan Times, a great place to make connections with people from all over the world. Her new friend, a French-Israeli artist called Lalenya, warns her 'You’ll need strength to stay in Japan. In this society we must roar like lions!' (p. 12).

The author isn’t looking for love when she meets Ichiro, a Taoist and specialist in acupuncture and massage at the White Crane Eastern Medicine Clinic in Tokyo. He’s so attentive she sees a future with this devoted Japanese man and the relationship gets serious. They marry at the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo.

At the beginning of the marriage, Grunberg Wakabayashi is surprised to discover similarities between the Jewish faith and Japanese religion. 'Ichiro had told me, Shintoism rejects statuary and forbids idol worship as much as Judaism does.' (p. 66). When her husband asks her questions about being Jewish, she’s unable to provide the answers and this gives her the impetus to find out more about the fundamentals.

This book is an eye-opener. There’s so much to learn about Judaism, Buddhism, Shintoism, and Taoism. For example, the reader may have heard of Shabbat, a 25-hour observance and Jewish rest period from Friday to Saturday sundown, but Grunberg Wakabayashi elaborates to clarify and inform. She explains why this custom is important and how the Torah can help one find inner peace and learn patience and self-restraint. Ichiro, on the other hand, educates his wife and the reader on his religious beliefs. He explains how Shakyamuni becomes Buddha in the foothills of Nepal and the way Taoism teaches its followers to be cheerful in frustrating circumstances.

A visit to the Chabad House in Omori, a Jewish place of worship, opens a whole new world for the author. Here, the Rabbi and his wife the Rebbetzin welcome every Jewish and Japanese person without discrimination. If they’d been ultra-orthodox this couple from Brooklyn would have scared her away but their relaxed style puts her at ease. She returns on a regular basis to learn about Jewish rituals, practices, history, and beliefs.

'Chabad had shown me the path into Jewish life that was fascinating and doable, small step by step, precisely because it was happening in Japan.' (p. 181).

It isn’t long before cracks in the marriage begin to show. Grunberg Wakabayashi makes allowances for this until she realises she needs to be wagamama or selfish if she’s going to be happy in the future.

As the story draws to a close, Grunberg Wakabayashi is convinced their lifestyle in Tokyo is too rigid for her and her kids and she leaves Japan. She wants her daughter Shoshana and her son Akiva to express themselves so they can reach their true potential. She takes her children to Israel and it’s here she finally feels her soul return to her body.

The voices of Grunberg Wakabayashi and her husband in this book are strong and the love and affection she has for her mother is transparent. More insight from Shoshana and Akiva about their opposing worlds would add to the story but the author is very protective of her children. This is reflected throughout the book. Shoshana has inherited her mother’s creative gene so maybe one day she’ll write her own memoir.

Grunberg Wakabayashi writes with sensitivity, humility, passion, and a delightful sense of humour. This book doesn’t discriminate. It shows respect for every person, race, and religion. Hebrew and Yiddish words complement the tone of the text, educating the reader on Jewish terms and traditions. The only criticism is their meaning isn’t always clear, but these words are few and far between and they can be Googled.

Interracial and interfaith marriages are becoming increasingly common. This is a story for anyone who wishes to gain insight into the extraordinary challenges people face as they navigate new worlds.

The aim of this memoir isn’t to convert the reader to Judaism, although this book repeatedly mentions the Torah and its significance. Instead, it inspires people to decide on their own spiritual journey. It proves there are alternatives if one is searching for peace of mind and a better life.

Grunberg Wakabayashi’s final comment in her Acknowledgements shows she possess inner grace and a heightened awareness of herself and others: 'As we set out on our separate paths, may we continue, like Noah, to remember that we are one lucky family to be given life on Earth, originating from the same boat.' (p. 255).