A Japanese Menagerie: Animal Pictures

British Museum Press, 2007, ISBN-13: 978-0-7141-2442-I, ISBN-10: 0-7141-2442-7, pp 112 including colour plates, £16.99.

Review by Sir Hugh Cortazzi

This delightful book will amuse all art and animal lovers and would be a very acceptable present in the Christmas stockings of adults as well as children.

Kyosai’s life spanned the end of the Edo period and the first decades of the Meiji era. He belonged to the Kano school of Japanese painting, but was also a master of the wood-block print. He was above all a superb draftsman and even in his cups, as he often was, he could dash off a humorous drawing with a few deft lines. He understood human foibles and delighted in satirising these in his paintings and prints.

Kyosai has been underestimated by some critics who saw him as a second-rate artist in comparison with Hokusai or the great masters of the Kano school, but attempts to rank artists in this way are specious. Kyosai may not be one of the world’s ‘greatest artists’ but he was a significant figure in the history of Japanese art and I regard him as a great artist. Josiah Conder, the British architect who contributed so much to buildings of that period, became his disciple and friend and many examples of his work found their way to Britain contributing to the development of Japonisme.

This book is not and does not pretend to be a book about Kyosai or the whole gamut of his art. It concentrates on his depiction of animals – hence the title ‘Menagerie’. Kyosai in depicting animals doing things normally associated with human beings was following in a long-standing Japanese tradition going back to the Chojugiga (Toba Sojo-emaki) of medieval times. Animals in Buddhist philosophy had souls like human beings and could aspire in rebirth to become humans and eventually reach Buddhahood. There was no absolute distinction between humankind and the animal kingdom.

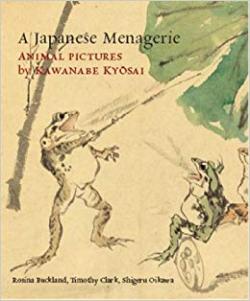

Kyosai, wanting to satirise the bureaucrats and the habits of his age, was inhibited by censorship from doing this too obviously. He accordingly depicted animals doing human activities. This did not seem strange to Japanese viewers. The satirical picture on the cover depicts a frog as a schoolmaster, pointing at a lotus leaf substituting for a blackboard and declaiming to frog pupils who are probably repeating the teacher’s words. This was produced at the time when universal primary education was being introduced. The book contains another charming sketch on a fan showing a frog postman by a telegraph pole; this was drawn at the time when Japan joined the universal postal union and established a national postal service. Another Kyosai picture of frog acrobats is exhibited on the stairs to the reopened Japanese gallery at the British Museum.

It is difficult in a short review to do more than mention some of the many other attractive and striking images in this book. I particularly liked that of a crow in a branch in winter and another of an egret in rain on a black background contrasting with a similar image on a white background.

Tim Clark, Israel Goldman, Rosina Buckland and Marie Conte-Helm

Tim Clark explained at the book presentation at Daiwa House on 7 November 2006 the striking sketch of a rabbit with a whip on a tiger as probably having been dashed off on New Year’s Eve, as under the signs of the zodiac the year of the tiger moved into the year of the rabbit.

The book contains informative articles by Rosina Buckland on ‘Kyosai and the Meiji-era Art World’, by Shigeru Oikawa on ‘Kyosai;s Comic Zoo’ and by Timothy Clark on ‘Human’ Animals in Japanese Painting. It also has a foreword by Israel Goldman whose collection of Kyosai animals inspired this book.

This review should rightly end with the cat and the mouse on the back cover.