Bungei Shunju, June 2008, 206 pages. ISBN 13: 978-4163701400. Paperback ¥1400

Review by Mikihiro Maeda

Global warming and climate change are spreading worldwide due to environmental destruction and degradation. On top of this, Cyclone Nargis hit Myanmar and caused a deadly natural disaster on May 2, followed by the Sichuan earthquake in China on May 25. Although ordinary citizens in Myanmar could not access water to drink and lost electricity after the storm, the military junta not only decided to reject visa applications for disaster experts and aid workers but also wanted only cash and aid in the beginning. Moreover, the junta went ahead with a referendum for a new constitution on May 10, only one week after the cyclone, and the junta concluded that almost all citizens supported the new constitution and the current regime.

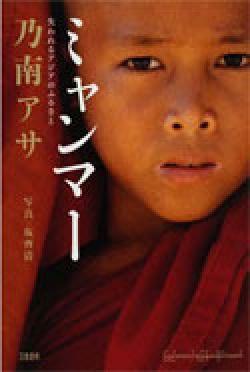

This book was published on June 15th, about one month after the tragedy. Well-known Naoki Prize winning novelist Asa Nonami wrote a travelogue with many beautiful photographs taken by Kiyoshi Sakasai. Even though the author makes plainspoken confessions of her experiences while travelling in Myanmar, her affection for the Burmese she met and her passion for her travel are well conveyed.

Early on in the book, she mentions the two names for the country–”Burma” and “Myanmar”–a dilemma for people who want to identify the state of the country. It is widely known that the pro-democracy movement against military rule was widespread in this country in 1988, and that a general election was held in 1990 for the first time in almost 30 years. The National League of Democracy (NLD) won a landslide victory in this election and Aung San Suu Kyi, leader of the party, earned the right to be Prime Minister. However she has been under house arrest by the military junta since 1989 and therefore prevented from assuming the leadership role. Those people who do not recognize military rule refer to the country as “The Union of Burma,” and others call it “The Union of Myanmar.” The author believes that the term “Myanmar” is more suitable for referring to this multiracial country, while the term “Burma” only indicates the Burmese, who account for 70 percent of the nation.

With respect to her relationship with Myanmar, Nonami initially did not include this country as a travel destination in her itinerary, but a terrorist incident forced her to change her travel plans. She chose Myanmar as an alternative destination. Once she arrived there she grew to like it very much and revisited Myanmar twice. Based on those visits, she narrates the story in a flowing style full of affection.

She often presents candy to children whom she encounters while travelling to ease their tension and to facilitate conversation (p75). She is impressed by the attitude of monks who diligently persevere day and night, and by citizens who live in a simple way diligently. She also recalls the old Japanese life style from her youth and thinks that the people of Myanmar live in peace that Japanese used to embrace, but worries that Japanese might lose this peace due to increasing affluence (p103). She also hopes that the citizens of Myanmar are able to have bright prospects for a “free society” in the near future (p147).

In the final part of this book, the author converses with a monk who loves and admires Japan because Japan has a rich and “free” society. But the monk feels that Japan is too far away from Myanmar and he cannot imagine when he will be able to visit Japan (p203). He also believes that Myanmar’s politics are not good for the citizens, who want to take part in a world community and indicated the outbreak of the protests by saying that something undoubtedly will happen soon (p200).

The 2007 crackdown against anti-government protests and Cyclone Nargis caused the author to wonder when she will be able to visit the country next, and she worries that if ever allowed to visit she probably will see some unimaginable impact of the crises on the scenery, the citizens, and the nation itself (p13). In the introduction of this book, she reveals that the main motive for writing it is that in case the Myanmar she knew never returns, at least her memories will be recorded.