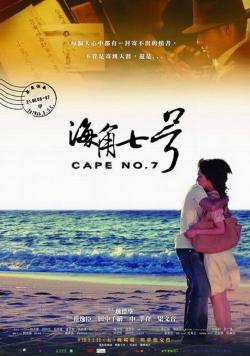

Cape No. 7

(魏德聖), 2008, 133 minutes

Review by Fumiko Halloran

The movie Cape No. 7 was released in Taiwan in August 2008 and earned a top revenue of NT$200 million in just a couple of months. It first arrived in the U.S. via the Honolulu International Film Festival held in mid-October 2008. This is where I saw it and was struck by the constant presence of Japan in the daily life of Taiwan even today.

The story features Taiwan under Japanese colonial rule, Japan’s surrender in World War II in 1945, a Japanese school teacher’s love for a Taiwanese girl, and his departure from Taiwan. He left her, even though she was willing to elope, because he had no idea what awaited him in a Japan that had been heavily bombed and faced starvation.

Fast forward to contemporary Taiwan: a young rock band singer and guitarist, Aga, who didn’t make it in Taipei, comes to Hangchun in southern Taiwan. He works as a temporary mailman. Among the mail to be delivered, he finds a package of letters written by the school teacher sixty years ago but never sent to his girlfriend. It turns out that after the teacher passed away in Japan, his daughter had discovered the letters and sent them to the old address in Hangchun. But that address does not exist today as the area has become a harbor.

Aga opens the package, reads the letters, and tries to deliver them. Meanwhile a Japanese model and music promoter, Tomoko, the same name as the Taiwanese girl (who was required to have a Japanese name during Japanese rule), meets Aga. She is trying to organize a local band for an opening performance at a beach concert by a Japanese pop singer, Kosuke Atari. Aga and Tomoko hate each other at the beginning, but gradually their relationship develops into a romance. Tomoko discovers that her hotel maid is a granddaughter of the original Tomoko, who is alive in her 80s, and tells Aga. After finally delivering the letters to the now old woman, Aga returns to play powerful music to the delight of the audience, proclaiming his love for Tomoko.

Throughout the movie, the languages are Mandarin, Taiwanese and Japanese, with English superimposed. The narration of the seven love letters is in Japanese, with Chinese and English superimposed. Chie Tanaka, the Japanese actress in the role of the young Tomoko, speaks Mandarin most of the time. In the beach concert, when Aga begins to sing “Wild Roses” (Nobara) in Japanese, Atari, the Japanese singer, joins Aga singing the lyrics in Mandarin. “Nobara” for many years was included in Japanese elementary school music education from pre-war to post-war years. The original lyrics in German (Heideroslein) are by Goethe and the music by Schubert.

In the pop music world, it is becoming increasingly common for Japanese singers to sing not only in Japanese but in Korean and Mandarin, while other Asian singers sing in Japanese. Just as Japanese fans rush to the airport to see their favourite Korean singers arriving at Narita, enthusiastic fans in Taiwan snatch up tickets for concerts by Japanese pop singers and bands such as Ai Otsuka and Arashi.

At the film’s Honolulu showing, the director, Wei Te-sheng, a quiet 40 year old man, answered questions from the audience. He spoke in Mandarin, which was translated into English. He said he wanted to make a movie about music and was searching for a theme when he read in a newspaper about the old mail that had not been delivered sixty years after the end of the war. He started to think what if those lost letters were love letters, thus a story was born. In addition to directing, Wei wrote the script.

The musicians in the movie were real but 90 percent of the cast had never acted before. He said everybody gets angry sometime as things don’t work out the way they wanted, and frustration drives us into some negative feelings. But you can work out things with other human beings and when they connect, something beautiful can happen. He said Taiwan is an ethnically and culturally diverse society and he wanted to depict that aspect, too.

I found it interesting that the treatment of Japanese colonial rule was free of political angles, concentrating on the complicated and sensitive emotions of individuals whose lives were affected by the tidal wave of history beyond their control. Director Wei said that by telling such stories, we come to understand the world better.