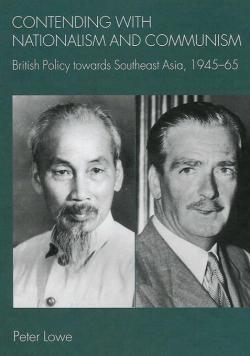

Contending With Nationalism and Communism: British policy towards Southeast Asia, 1945-65

In series Global Conflict and Security since 1945, Palgrave Macmillan, 2009, 312 pages including notes, bibliography and index, ISBN 978-0-230-52123-0

Review by Sir Hugh Cortazzi

Peter Lowe presents in this study a clear account of the complex and often inter-related problems in Southeast Asia which faced British ministers and officials in the first twenty years after the end of the Second World War. It is based on meticulous research in the National Archives. Memoranda, minutes, official despatches and telegrams from British missions in the various capital are quoted in ways which bring out the difficulties faced by the British government in an area of the world which was no longer central to British word interests but which could not be neglected, if only because of residual imperial responsibilities and the wider international ramifications of the issues involved. Not the least of these were the implications for Anglo-American relations which is a theme running throughout this book.

Lowe concludes (page 247) that “Overall British politicians revealed a certain arrogance in their diplomacy with their counterparts in Southeast Asia; at the same time they understood the processes at work and British policy demonstrated flexibility and a willingness to compromise.” He notes that “Communism was identified as the principal threat in 1948. The menace was exaggerated in the later 1940s and early 1950s…The communist threat was real but not as comprehensive as feared.” Britain was forced to recognize that independence for Malaysia and Singapore as the price they had to pay to defeat the communist threat. “British ministers and official employed a blend of pragmatism and judicious concession in negotiating with nationalist leaders; they knew that time was not on the side of colonial empires.” There were reactionary British officials especially in Burma in the early post-war years, but French and Dutch ministers and officials were more wedded to colonial rule than the British. Such colonialist attitudes complicated and delayed solutions in Indo-China and Indonesia.

Peter Lowe’s study does not deal directly with Japanese involvement with the problems of Southeast Asia in the years covered by this study, but the unrest and destruction throughout the area were, of course, the result of the war and Japanese occupation. The Japanese were also responsible for inflaming nationalism in the Asian countries which they occupied, although as Lowe points out (page 12) “The Greater East Asia Co-prosperity Sphere, as implemented by Japan between 1942 and 1945, represented the imposition of Japanese imperialism rather than liberation: most Japanese were interested primarily in exploitation of Southeast Asia for economic and military purposes.” In indo-China after the Japanese surrender “the British suspected that the Japanese were assisting Vietnamese revolutionaries” (page 31). Japanese forces in Indonesia were also a problem for British and Indian forces which moved into Java in September 1945. Esler Dening, who was sent to Java in October 1945, and who had served for many years in Japan before the war (he later became the first post-war British Ambassador to Japan) (page 35) “was alarmed at the role played by the Japanese: ‘I have come to the conclusion that the Japanese have left underground organizations throughout South-East Asia, and in view of their known methods …they are likely to be very hard to detect’”. “Between 1945 and 1948 British ministers and officials wrestled as best they could with the legacy of Japanese occupation of Southeast Asia” (page 41).

Against this background and with memories of Japanese atrocities still fresh in ministers’ minds it was not surprising that the British were reluctant to see Japanese adherence to the Colombo plan (designed to assist recovery in the area) when the issue was discussed in 1951/2 (page 76). The Japanese were in due course admitted and a Foreign Office planning paper produced in 1959 declared (page 79) that “The West should work with Japan for three reasons: to discourage cooperation with communist states; to build Japan as a counterweight to China and to utilise Japan’s valuable experience as ‘the only fully industrialised Asian power.”’ Japanese membership of SEATO was never a possibility. The British regarded Japan as “disruptive” (page 92); in any case Japan would have been precluded by the post-war constitution from joining such a defence pact.

Lowe in his chapter on “Britain, Indonesia and the Creation of Malaysia” refers to the Japanese role in attempts to end “confrontation,” but does not comment on this in much detail. Perhaps we in the British Embassy in Tokyo put too much stress on what we saw as Japanese meddling and on the undisguised pro-Sukarno attitude of many Japanese officials particularly Oda Takio, the vice-minister at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs who had been Japanese Ambassador in Djakarta. In this context readers should look at pages 196/7 of my portrait of Sir Francis Rundall, the British Ambassador at that time, in British Envoys in Japan 1859-1972, published by global Oriental in 2004 and “Marked for Peter Lowe”

Peter Lowe’s carefully researched study should be read by anyone interested in the end of empire in South-East Asia and the various conflicts and tragedies which disturbed the peace in the area in the first twenty years after the Second World War.