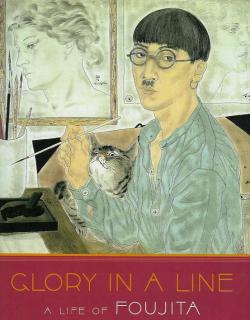

Glory in a Line, a Life of Foujita, The Artist Caught Between East and West

Faber and Faber, 2006, 331 pages including index and endnotes , ISBN-13: 978-0-571-21179-1 (hard cover)

Review by Sir Hugh Cortazzi

Leonard Foujita was the name Fujita Tsuguharu (or Tsuguji) adopted when late in life he became a catholic. Foujita (1886-1968) is probably the most famous of the numerous Japanese artists who were attracted to Paris and settled in Europe. His father was a military man but accepted his son’s determination to become a painter and consulted the famous Japanese author Mori Ōgai who suggested that the boy should study at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts where he enrolled as a student under the well-known artist Kuroda Seiki who, however, did not appreciate Fujita’s efforts.

In 1913 Foujita managed to get away from Japan and arrived without his wife Tomi in Paris where he was introduced to Van Dongen and other artists including Picasso, Diego Rivera, Modigliani and Soutine. He plunged into the artistic life and enjoyed himself greatly but he never took to wine or other alcohol. Phyllis Birnbaum notes that Foujita’s “studio was spotless and orderly, in contrast to the filthy disarray that came naturally to his friends.” He adapted to French ways of life but he “often remembered Japan in alternating bouts of pride and shame.” He found life in wartime (1914-18) France difficult and spent a year in London.

When Foujita returned to Paris he met Fernande Barry who in due course became the second of his five wives. The French accepted Fernande, but the Japanese community did not. Nina Hamnett said that Fernande “screamed at Foujita most of the time…Foujita was angelic and never answered back or said a word.” Foujita concentrated on painting in oils. Gradually he moved away from bright colours and limited himself mostly to “black, brown and white.” He was influenced by a wide range of art schools including Cubism and Henri Rousseau, as well as Japanese traditions; French critics preferred his “more familiar Japanese effects.” During 1917 and 1918 he “exhibited close to four hundred works.” Phyllis Birnbaum thinks that “Foujita at last achieved his goal sometime around 1921, in a painting such as My Room, Still Life with Alarm Clock.

Foujita met his third wife Youki (Lucie Badoud) in 1923. “She was his goddess, his charm, his key to bankruptcy.” She was a frequent model for his nudes. Foujita soon became the most famous Japanese in Paris. His fame “spread even further across France when Foujita figured in a protest involving a naked woman and artistic freedom.” The Japanese in France were “intensely critical of his boisterous public image.”

Foujita perhaps surprisingly did care and for two years he travelled in Latin America with a new companion Madeleine Lequeux, a former dancer at the Casino de Paris. In Brazil he received many commissions which at least covered his travel expenses. But Japan was becoming increasingly unpopular in Europe and he decided not to return to France but instead to Japan. Madeleine as a former showgirl had plenty of opportunities in Tokyo, but she was soon bored. She left him for a year, but soon after she had returned to Tokyo she died of a stroke.

Fujita’s paintings sold well in pre-war Japan and his conceit grew. In 1936 he declared: “I take pride in believing that I am the world’s number one artist.” He tried to diversify and extend his contacts “with the lives of the general population” and for a brief time took to making a film. He had begun his Japanese phase. Born into a military family and piqued by his current unpopularity in France he was easily won over by the military who recruited him as a war artist. There seems little doubt that Foujita’s patriotic ardour was aroused and that he threw himself enthusiastically into his new role as a war artist. This took him to Nomonhan and other war zones. He did a number of paintings of the Japanese occupation of Singapore, of the fighting on Guadalcanal and the Solomons. He had, he declared, “broken with France.” He became the administrator of the Japanese Army Art Association where he seems to have enjoyed the power it gave him over other Japanese war artists.

After the war Foujita found friends among the US occupation forces and he managed to return to France via the United States with his fifth wife, Kimiyo, a Japanese, like his first wife. They became French citizens in 1955 and retired to the country.

Inevitably there have been many controversies about Foujita’s life and especially his support for the Japanese military in China and East Asia. Phyllis Birnbaum deals with these as objectively as is possible and gives an interesting account of Foujita’s life. But the most important question is the nature of and extent of Foujita’s achievements as an artist. Foujita clearly was a very accomplished artist and draughtsman, but where does he rank among twentieth century artists? Unfortunately this book, which contains only a single section of black and white photographs of works by Foujita, is inadequate to enable readers to make up their own minds on his artistic merits. Phyllis Birnbaum has done some meticulous research, but there are gaps (for instance there is nothing in this book about Foujita as an illustrator of that classic piece of irony about Japan L’Honorable Partie de Campagne ) and this is not the definitive work about Foujita.