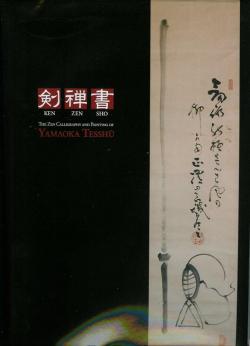

剣禅書 Ken Zen Sho, The Zen Calligraphy and painting of Yamaoka Tesshū

Published by Bunkasha International Corporation, Tokyo, 2008, ISBN4-9901694-8-4

Review by Sir Hugh Cortazzi

This book was prepared as a catalogue and guide for an exhibition, held between 3 September and 14 December 2008, in the Toshiba Gallery of Japanese Art at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. It commemorated the 120th anniversary of the death of Yamaoka Tesshū (1836-88) and was based on the collection of his calligraphy which belonged to the late Terayama Tanchū (1938-2007) who was himself a master of ken-zen-sho (the sword, Zen and calligraphy). The book has a foreword by Rupert Faulkener, introductions by Sarah Moate and Alex Bennett, an essay by Terayama Tanchū on the relevance of “Swordsmanship, Zen and Calligraphy” plus an afterword by Takemura Eiji. Some 34 colour plates illustrating calligraphy, mainly by Tesshū, are accompanied by translations and explanations. Copies of this book may be purchased from the Victoria and Albert Museum’s shop and from the Bunkasha International (Kendo) web site.

Yamaoka Tesshū was a samurai who began to learn swordsmanship at the age of nine. He also learnt calligraphy, studied Confucian philosophy and later Zen. He became an instructor at the military academy of the shogunate (Kōbusho). In 1867 just before the outbreak of the civil war which led to the Meiji Restoration he was sent to negotiate on behalf of the shogun with Saigō Takamori, who was in command of the forces opposed to the shogunate. After a heated discussion an understanding was reached which ensured that there was a relatively peaceful transfer of power. After the Restoration, Tesshū held a number of important posts including that of governor of the Shizuoka domain and of Ibaragi prefecture. In 1872 he became a lifetime retainer of the Emperor and worked for the Imperial Household. He founded the Zenshōan temple in Tokyo where his grave is located and where books and manuscripts relating to swordsmanship, tactics and military philosophy are kept. These include a rare manuscript of the thirty-five articles on strategy by the famous Miyamoto Musashi whom the students of Ken-Zen-Sho revere as the outstanding master.

Tesshū is “renowned for his statement that swordsmanship, Zen and calligraphy are identical in their aspiration to the no-mind. Known in Japanese as mu-shin, it is a state beyond thoughts, emotions and expectations.” Tesshū, according to Suzuki Daisetsu, the interpreter of Zen to Engish readers, knew that “A man has to die, and leave his ordinary consciousness in order to awaken the unconscious.” Alex Bennett in the introduction part 2 notes that in budō (the martial Way) ‘the goal was to ‘give life’ rather than take it. The martial traditions …gradually developed a ‘spirit of non-lethality’ akin to Zen.” Swordsmanship, Zen and calligraphy (brushwork) were equivalent to one another; “one was not superior to the other, as long as the adept surrendered himself unconditionally to his ascetic quest.” Sarah Moate in the introduction part 1 says of calligraphy that “In Zen terms it reveals the depths of the Zen calligrapher’s state of being, as discernible in the physical traces of sumi ink brushed on paper in the immediacy of the moment, which are directly and spontaneously painted with no retouching.” Tesshū’s calligraphy of a snowman (yuki Daruma –雪だるま) expresses what he saw as the essence “vast emptiness, nothing sacred.” These quotations are not an adequate summary of the philosophy of ken-zen-sho, but they do reflect some of the issues which someone not trained in Zen faces when trying to understand and appreciate the images in this book. Zen which is central to swordsmanship and calligraphy cannot be summed up in a logical way.

The essay by Terayama Tanchū is an excellent survey of the three themes of swordsmanship, Zen and calligraphy. He points out that calligraphy “was perceived as being far more profound than just writing visually pleasing characters. For this, the most important ingredient was spirited utilisation of one’s ‘primary life.’”

Anyone interested in Zen calligraphy will find much of interest in this book.