Minshuto Kaibo and Minshuto No Yami

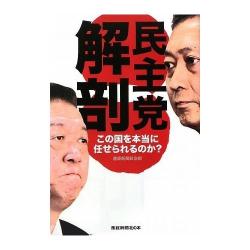

Minshuto Kaibo, by Sankei Shimbun Political News Division, Sankei Shimbun-sha No Hon, July 2009, 228 pages, 1300 yen

Minshuto No Yami, by Keisuke Udagawa, Seiko Shobo, July 2009, 253 pages, 1575 yen

Reviews by Fumiko Halloran

The Sankei Shimbun and Keisuke Udagawa books reviewed here were published before the 30th August 2009 general election, and were best sellers snatched up by voters who were eager to learn more about the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) and how the party would steer a course head for the country.

Udagawa’s rambling book focuses on new elected Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama’s criticism of the bureaucracy as unrealistic, on his support for voting rights for foreign permanent residents (mostly Koreans) as dangerous and unconstitutional, and on his generous social welfare programs as lacking financial resources. The author devotes three chapters to several financial scandals that could undermine the accountability of the Hatoyama regime. The author warns readers, many of whom wanted major changes in politics, not to be swept up by a superficial political tide but to look at the Democratic Party of Japan as it is.

The analysis in the Sankei Shimbun book is far more thorough, with a list of DPJ proposals on each issue. Interestingly, while Hatoyama as the head of the DPJ is prominently written up in the first chapter, the rest of the book gives much space to Ichiro Ozawa’s role in the party and future elections. Sankei foresaw the double power centres in the party. Ozawa resigned as head of the DPJ after the arrest of one of his assistants who was allegedly involved in illegal financial contributions from a construction company. Ozawa, however, controlled campaign strategy for the 30th August general election that brought a sweeping victory to the DPJ. Prime Minister Hatoyama thus appointed Ozawa as party secretary general. Ozawa is known for his controversial remarks such as Japan needing only the U.S. Seventh Fleet to be based in Japan for the nation’s protection. How much Hatoyama can rein in Ozawa remains to be seen. Whether Ozawa continues to have ambitions about becoming prime minister also remains to be seen. Political observers say that the financial scandals embroiling Ozawa along with his health problems, he has suffered heart attacks in the past, might be a handicap.

From these two books and the review of the Hatayama study above, one gets the impression that Yukio Hatoyama has several faces. He is an idealist who advocates the spirit of “fraternity” (友愛 Yu-ai), a slogan in the French Revolution. He is a liberal who advocates social welfare state that is kind to those in need. And he shows signs of a Machiavellian politician who plays hardball. Born into a wealthy family, his remarks on the poor and the unfortunate often sound out-of-touch. Yet he is quick to shift position to keep power. The scrutiny of Japan’s new Prime Minister’s political leadership and his stand on various policies shows that the future of his new regime is impossible to predict.