Hyperart: Thomasson

Review by Adam House

Walking back from a lunch break, Genpei Akasegawa and two friends had walked passed what has now come to be known in the world of Hyperart as, ‘The Yotsuya Staircase’, unconsciously walking up one side, walking along the small platform and then walking down the opposite side. A small flight of stairs, seven in all on each side, with a wooden banister, much the same as many other stairs, although when looking at it, something was amiss, usually the platform would lead to a door, but here there was no door, looking at them, they seemed to be a completely useless flight of stairs. Perhaps at some distant point in the past there had been a door at the top but now no longer there, it had rendered the stair’s use obsolete. On closer inspection they came to see that a section of rail from the banister had actually broken off and been replaced by a new piece of wood. They surmised that not only was it functioning as a staircase that actually led to nowhere and was also being preserved and maintained as such. So begins Genpei Akasegawa’s book which originally appeared as columns in photography magazines from the mid-eighties. It was published in Japan by Chikuma Shobo Publishing back in 1987.

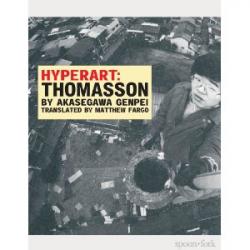

Realizing that he was moving on from l’art pour l’art, to le stairs pour le stairs maybe, Akasegawa termed this art ‘Hyperart’, and debating it over with his students they decided they needed a more precise name for their discoveries, and they came up with the name Thomasson. Gary Thomasson, a baseball player who had then been recently signed by the Yomiuri Giants, encapsulated everything that the art signified. Since starting his career with the Giants he had failed to make contact bat with ball, although being paid a mint he served no great purpose. So the momentum for the hunt of Thomassons begins and they discover the ‘defunct ticket window of Ekoda’ (sealed with plywood), ‘the pointless gate at Ochanomizu’,(looks like a gate but is completely sealed with concrete),mysterious eaves that jut out of walls protecting vanished mail boxes of long ago. Many examples prove to be puzzling to solve, like a floating doorway appearing in a wall that belongs to the basement of a house? The photograph used as the book’s cover comes from a reader’s report in Urawa. Noticing a wall of a drycleaner’s that appeared to have a blip in the middle, closer inspection revealed that it was in actual fact a doorknob for a door that had been sealed over. The reader concludes his report, “what’s more, the doorknob actually turned.”

Soon with numerous reports of sightings and photographs being sent in by magazine readers, some from as far as Paris and China, it became clear that Thomassons were not only a Japanese phenomenon, but could be found wherever humans create buildings. Collecting together paintings, models and photographs, Akasegawa hosted the world’s first exhibition of Thomasson artefacts which he called “A Neighbourhood in Agony,” and interest was such that bus tours were organized around Tokyo to visit the various Thomasson locations. Although told in a compère like prose, the book explores the unconscious side of architecture, which in turn has created some truly inspiring curious objects which question what we think of as art and what constitutes architecture. Probing into these architectural oddities, Akasegawa observes that “The city itself was just an instance, a fleeting phenomena.” These pieces seem to appear to us, like they’ve floated up from an archaeological dig.

Translated by Matt Fargo, who provides a summary of his thoughts about translating the book, Reiko Tomii also provides an in-depth essay on Akasegawa Genpei, who under the pen name Katsuhiko Otsuji won the Akutagawa Prize for fiction in 1981. Akasegawa is also a key figure in the modern Japanese art world since the sixties, being involved with the art groups Hi Red Center and Neo Dada. The book is full of many photographs and if you have seen a Thomasson, the book also provides report sheets to fill in, to see more go to http://thomasson.kaya.com.