New Architecture in Japan

By Yuki Sumner

Naomi Pollock with David Littlefield

Photography by Edmund Sumner

Merrell, London and New York 2010

272 pages including index, copiously illustrated in colour throughout

ISBN 978-8589-4450

Review by Sir Hugh Cortazzi

This survey of new architecture in Japan was introduced at a launching party at Daiwa House on 24 March 2011 with talks by Yuki and Edmund Sumner. The book features buildings by well known Japanese architects such as Tadao Ando but also projects by new younger architects as well as by international practices including such famous names as Rogers and Foster. It is not and does not claim to be a survey or history of modern architecture in Japan. It is essentially an introduction to new architectural ideas and themes in Japan and covers a wide variety of public and private buildings. The photography is outstanding and makes it possible for the reader to envisage the buildings and their surroundings.

Travelling through Japanese towns and cities and looking at Japanese buildings from trains, buses or cars leaves most visitors appalled by the drab uniformity and ugliness which has been imposed on Japan’s natural beauty. The concretisation of the Japanese landscape has seemed to be the aim of Japanese construction companies and the road lobby which was so successful with Liberal Democratic Party governments which built roads and bridges to nowhere as if there was no tomorrow. Preservation of the old buildings is not something to which many Japanese have attached much importance until recently. A visitor to modern Kyoto will at first wonder how such eyesores could be imposed on the ancient capital of Japan. Attitudes are, however, now changing and the preservation of old Kyoto looks more secure, but the tradition, perhaps because Japanese buildings were mainly made of wood, has been to replace buildings after a generation or so has passed. As Naomi Pollock points out in her article on “Architecture in Japan in Context” Japan seems to have an “insatiable appetite for the new.”

Perhaps if the architects whose buildings are illustrated in this book are given the chance we shall in the future be able to look at Japanese towns more in keeping with their surroundings. As Yuki Sumner points out in an essay on “The Residue of Japan-ness” young Japanese architects in their “lightness of touch and use of flowing space” which are undeniably Japanese in character “can be traced back to an earlier generation of architects such as Fumihiko Maki and Yoshio Taniguchi.” She notes that Arata Isozaki, another famous Japanese architect, identified two kinds of Japan-ness. One was the “earthy, more dynamic or ‘populist’ aesthetic of the Jomon period and “the more elegant, even aristocratic” or “elitist” aesthetic of the Yayoi period.

For someone living in England where investment in infrastructure and public buildings has been limited by a shortage of funds and probably also of imagination, this book with its photographs of such public buildings as railway stations, schools and art museums will surely excite some envy, but as Naomi Pollock notes of some of the museums though beautifully designed ended up as under-utilized hako-mono (empty boxes) as the buildings came before the content had been collected.

It is difficult in a short review to do justice to the wide variety of buildings illustrated in this volume. In the first section devoted to “Infrastructure and Public Spaces” I was particularly impressed by such buildings as the Hanamidori Cultural Centre in Tachikawa (pages 38/9), the Meiso no Mori Municipal Funeral Hall in Gifu prefecture (pages 42-45), the Naka Incineration Plant at Hiroshima (pages 46/7) and the Tokyu Toyoko-Line Station at Shibuya (pages 52/3).

Meiso Memorial Hall

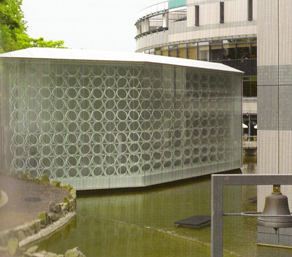

In the second section headed “Culture” I thought that the “Design Sight” Minato, Tokyo (page 58), designed by Tadao Ando and associates, fitted well into its surroundings and was an imaginative and striking design.

‘Design Sight’

One of the most impressive of the art galleries illustrated in the volume seemed to me to be that of the Aomori Museum of Art (pages 62/63). A few, however, struck me as too way-out such as Gallery Sora, Chuo, Tokyo (pages 68/9). I thought that the Kanno Museum of Art near Sendai “a pure metal box built to house a collection of metal sculptures” (pages 74/5) was an ugly eyesore.

Kanno Museum

The Nemunoki Museum of Art in Shizuoka prefecture (pages 82/3) on the other hand seems to fit well in an elegant way into the surroundings.

The section devoted to “Sport and Leisure” includes some buildings such as the Fujiya Inn in Yamagata prefecture (pages 102/3) and the House of Light inn Niigata prefecture (pages 104/5) which owe much to Japanese traditional architectural styles. The Takasugi-an (pages 122/3) struck me as inappropriate and ‘way-out,’ trying to be clever by being different

In the section devoted to “Education” I was particularly impressed by the Gifu Academy of Forest Science and Culture (pages 144/5) and the Rikuryo Alumni Hall in Osaka (pages 162/3). Some of the modern temples in the section devoted to Health and Religion are interesting and impressive e.g. White Chapel in Osaka (pages 182/3).

White Chapel

I was less impressed by the examples in the section devoted to “Houses and Housing.” Some designs seemed to have been conceived by a desire to attract attention, although in some cases the designers have made an imaginative use of limited space. The Section on “Offices and Retail” again shows that some Japanese architects put more emphasis on being different than in practicality and fitting into the surrounding buildings. I thought F-Town in Sendai (page 238/9) and Showroom H in Niigata prefecture (pages 260/1) ugly and inappropriate. Others more attuned to the excesses of modern architects may disagree.

Anyone interested in modern architecture in Japan will enjoy this book