International Architecture in Interwar Japan, Constructing Kokusia Kenchiku

Ken Tadashi Oshima

320 pp., 220 illustrations, notes, glossary, bibliography and index

ISBN 978-0-298944-0, University of Washington Press, 2010

£46

Professor Oshima, the author of this book, is associate professor of architecture at the University of Washington and was a research fellow at the Sainsbury Institute for the Study of Japanese Arts and Cultures in Norwich. One of his previous studies was on the British 19th century designer Christopher Dresser who was greatly influenced by Japanese art and design.

In this book Oshima traces ‘the rise of international architectural practices in Japan during the pivotal interwar decades by looking at the design and construction of private and public buildings by three modernist architects: Yamada Mamoru (1894-1966), Horiguchi Sutemi (1895-1984), and Antonin Raymond (1888-1976). Each in his own way sought to create a new architecture comprising modern forms, materials and programs, at once responsive to the physical and socio-cultural context of Japan yet fully reflective of an emerging international idiom.’ He notes that the three architects ‘represented three modes of architectural practice; Horiguchi, the independent, dandy, academic, architect; Yamada, the socially engaged government architect; and Raymond [who was of Czech origin and had come to Japan in 1919], the architect as foreign specialist with a large bourgeois client base.’

Oshima describes the beginnings of international architecture in Japan and notes that non-Japanese architects in the Meiji era ‘often embraced elements of pre-modern Japanese architecture in their Meiji-period designs more eagerly than their Japanese counterparts.’ Japanese architects in the inter-war years sought a hybrid between Japanese and western designs. The materials used by western architects were mainly stone and brick. The traditional material in Japan was wood. In the Yokohama earthquake of 1923 neither traditional western nor Japanese materials were adequate to withstand the shocks and the subsequent fires. Japanese architects accordingly became enthusiasts for steel reinforced concrete as their main construction material.

All three architects began life in the countryside and were at heart artists. ‘Raymond first directly observed Japan as an idyllic landscape and culture.’ Horiguchi and Yamada were founder members of the Bunriha, a group of architects whose manifesto, according to Oshima, ‘was an attack against the increasing political strength of the structural faction and the historicism of the design faction among the architects at Tokyo Imperial University.’ (This sentence is not easy for the non-specialist to understand). Horiguchi was ‘the intellectual leader’ and Yamada ‘the spiritual leader’.

Most of the public buildings designed by Japanese interwar architects were either destroyed as a result of the war or have been replaced by more modern structures but some of the houses which they designed and which attempted to combine western and Japanese elements have survived. These give some idea of the lines on which inter-war architects were working.

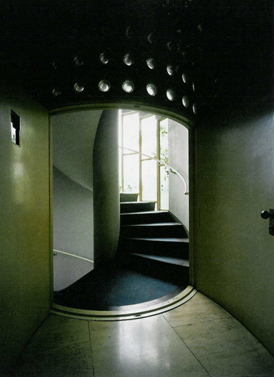

Here are two illustrations of a house which Yamada Mamoru designed for himself and which indicate how the Japanese and western elements were combined:

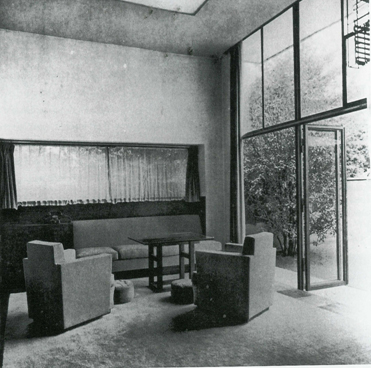

The following is another example of a western style sitting room with Japanese elements in a house designed by Horiguchi:

Tokyo Golf Club which was designed by Raymond and which still operates is a good example of his style of design:

Any one interested in the development of modern Japanese architecture would find this book and its copious illustrations instructive.