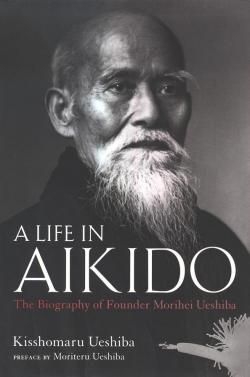

A Life in Aikido: The Biography of Founder Morihei Ueshiba, by Kisshomaru Ueshiba (植芝 吉祥丸)

A Life in Aikido: The Biography of Founder Morihei Ueshiba

by Kisshomaru Ueshiba (植芝 吉祥丸)

Kodansha International, 2008, 320 pages, ISBN-13: 978-4770026170

Review by Hugh Purser

One would be forgiven for thinking that this book was designed for the connoisseur (of aikido [合気道], if not Japanese history and culture as well) rather than the casual reader. Maybe this is the intention: the official biography of Aikido’s Founder (開祖), known to all as O Sensei (大先生 – the great teacher), written by his son for the community of aikidoka (合気道家 – aikido practitioners). But that would be a pity. There is much more here to satisfy broader interests, especially in the detailed accounts of life in Japan in the early part of the 20th century, the birth of the Omoto religion (大本教) and Japanese involvement in Mongolia and Manchuria. One is well into the second half of the book before the author writes “from this day in 1925, our Aikido took its first step forward.” By then, Ueshiba was already 42 years old, and he had just experienced enlightenment or what he called “a divine transformation.” In fact, the first chapter is given to describing his art as “kami-waza [神技] – an ability that seems heavenly rather than merely human.” For some, this could be a pretty intimidating concept.

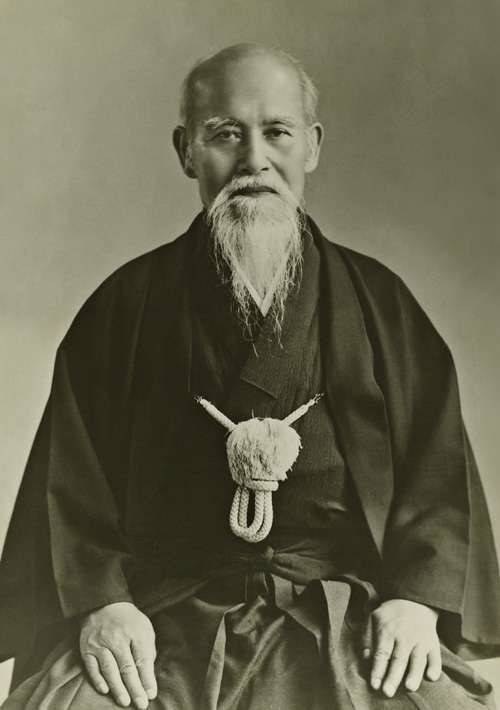

Morihei Ueshiba’s (植芝 盛平) martial arts abilities and exploits are legendary. But how did a ‘new’ martial art come about? And what were the influences on, and the characteristics of, the man who was responsible for it?

The picture that emerges is complex: a man of immense physical strength, dedicated to a severe discipline of physical and mental training in several martial arts; an entrepreneur, farmer, community leader and activist; at once both selfish in terms of seeking his own path, yet with the greater good in mind, with little interest in personal financial gain. One commentator wrote: “He was simply a person with a very high sense of responsibility and mission.” A man, too, influenced deeply by life changing events, such as the time in 1924 in Mongolia, when he was minutes away from a premature end at the hands of a firing squad; and his profound experiences in his companionship with Master Onisaburo (出口 王仁三郎), the founder of the Omoto religion. These latter events may explain why someone already heralded as the leading martial artist in Japan (at least in jujutsu [柔術] and aiki bujutsu [合気柔術]), would proceed to forge a new art which centered on “universal harmony, protection and divine love,” with a major role to play in everyday life. By 1926 Ueshiba was providing demonstrations to the great and good in Tokyo as a guest of Admiral Isamu Takeshita (竹下勇). The audiences (and later, students) included military officers, members of the imperial household, financiers and leading business figures – patronage which we might only envy today, particularly in the West. This gave aikido a sound platform for its advancement in the years ahead. It is also noteworthy that even at this early stage, aikido rapidly became popular with women, and continues to be so.

The outbreak of war caused setbacks, especially in attendances and revenue, and it took until the early 50s for stability and growth to resume. In 1941 Ueshiba began the development of the dojo (道場) and shrine at Iwama (岩間町), still considered the spiritual home of aikido (the term itself coming into popular use at the same time).

New dojos opened across Japan, and then internationally, arriving in the UK in the mid-50s. Many well known senseis spread the art far and wide – with a fair degree of diversity, it should be said. This is because Ueshiba’s aikido was continually evolving, and

those who trained with him at specific periods of his life would have witnessed different elements of that evolution. Perhaps this was the Founder’s most fundamental gift to modern (mostly part time) practitioners – that, within the framework of the core

principles he laid down, we should seek to continuously evolve, in mind and body, and above all, apply his teachings in our everyday life.

This book is a fascinating read, although a future printing would benefit from additional notes as well as an index (the Japanese original dates from 1978, but it has only recently been translated and published in English). It is recommended to all with an interest in Japan: then go and find your nearest dojo, and experience the real thing!