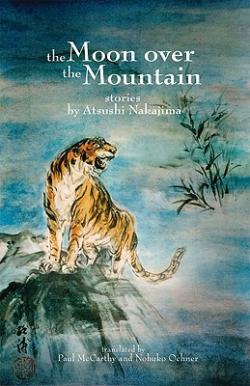

The Moon over the Mountain and Other Stories

By Atsushi Nakajima, Translated by Paul McCarthy and Nobuko Ochner, Autumn Hill Books, 2010, 182 pages

ISBN:9780982746608

Review by Adam House

Atsushi Nakajima (中島 敦) was born in Tokyo in 1909, his father came from a family of scholars specializing in the classics of ancient China, this would not only influence his reading but would inform the majority of his writing. The stories included in The Moon over the Mountain (山月記) were originally published in Japan in 1942-1943 and are mainly situated in ancient China, many in the ancient northern state of Qi (齊). After leaving Tokyo University, Nakajima took up a teaching post whilst at the same time beginning to write short stories and beginning the manuscript for his novel Light, Wind and Dreams (光と風と夢), which was translated by Akira Miwa (Hokuseido Press, 1962),a novella of the life of the Scottish writer Robert Louis Stevenson which was published in Japan in 1942,the same year as Nakajima’s premature death at the age of 33. Nakajima who suffered from asthma for most of his life died from pneumonia. Nakajima seems to be strikingly at odds with other writers of his generation for not writing about the war.

The Moon over the Mountain is the first collection of stories by Nakajima to appear in English, translated by Paul McCarthy and Nobuko Ochner and published by the not for profit independent publisher Autumn Hill Books. The first story Sangetsuki (山月記), which is also well known as The Tiger Poet (人虎) is one of Nakajima’s most well known stories, it was studied in Japanese schools. A tale of a frustrated poet, Li Zheng (李徴), who gives up his post as a local official to devote himself to poetry, although failing in his attempt to fulfil his life’s desire of becoming a great poet he falls into madness and one night runs off into the wilderness after hearing his name being called. This violent emotional change within himself also appears to provoke a physical transformation. The narrative jumps forward slightly and takes up with Yuan Can an old acquaintance of Li Zheng’s who is travelling into an area known for being a domain of a wild tiger. After some time Yuan Can’s party hear the roar of a great tiger coming from the bush, but as they draw near Yuan can hear the sound of human sobs. Li Zheng begins to tell of his misfortune and laments over his transformation and Yuan Can begins to recognize that the voice he hears belongs to that of his old friend Li Zheng.

Transformation seems to thread in and out of these stories, in Sangetsuki it is seen as a manifestation of suffering and later in the story “On Admiration: Notes by the Monk Wu Jing” it appears as a well sought after craft and a sign of attainment in a story observing the nature of a fellow monk. Nakajima’s finely crafted stories blend existential inquiry with that of ancient Chinese storytelling, where the human and animal world often blend, in the story The Master, a young archer who wants to master his skills, turns out to be a danger to his tutor who refers his student to a mountain hermit for further instruction. He teaches him the art of to “shoot without shooting” in a story that turns the notion of learning on its head. Many of the stories are set in the Qi state and tell of courtly intrigue and can be read as resembling morality tales, where those who appear to be wronged sometimes find their end after being the perpetrators of wrong doing, the stories defy predictability. As in the story Forebodings which begins with arguing warriors and ends with the states of Chu and Chen at war, at the centre of this narrative is the beguiling beauty of Xiaja whose beauty subtly wields a destructive power.

Nakajima’s stories often drop subtle clues and pointers which will often end up being the decisive thread as in Waxing and Waning which again has a courtly setting, an exiled Duke patiently waits for revenge trying at the same time to contain familial power games, the reader cannot afford to miss a line in Nakajima’s finely written narratives.