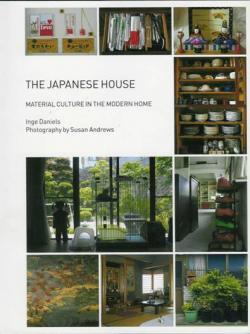

The Japanese House, Material Culture in the Modern Home

by Inge Daniels, Photography by Susan Andrews, Berg, Oxford and New York, 2010, 243 pages including notes, bibliography and index, copious illustrations in colour, ISBN 978-184520-517-1 (Paper)

Review by Sir Hugh Cortazzi

Until the Second World War individual Japanese houses retained some elements of the aesthetic which so pleased and inspired Edward Morse [author of “Japanese Homes and their Surroundings” – 1885], Bruno Taut [author of “Houses and People of Japan” – 1938] and others. In the war huge swathes of Japanese cities were destroyed by bombing and fire. Japan’s housing stock had to be almost completely replaced. Except in some country areas and in a few exclusive urban districts, the old style individual house generally ceased to exist.

Japanese people also began to seek western style comforts and found the sparse heating provided by hibachi (火鉢) and kotatsu(炬燵) inadequate. Japan’s population expanded. Space was at a premium and most living accommodation was cramped. The 1960s and 1970s was the era when, to quote the notorious and exaggerated phrase of the late Sir Roy Denman “Japanese were work-aholics, living in rabbit-hutches.”

It has been a long standing tradition in Japan that houses which are not meant to last more than twenty or at most thirty years should be regularly rebuilt and modernised. This has meant in a country so prone to earthquake and natural disaster the replacement of a large proportion of wood frame houses by stronger structures. The need to cram more people into a limited space also meant the development of modern housing blocks, called “mansions” in Japanese to distinguish them from the tawdry apartment blocks put up in the immediate post-war era.

This book attempts to describe the development of modern housing in Japan and focuses on the lives of ordinary people rather than on the elite. It contains much of interest to the general reader who wants to learn more about modern Japan. The photographs, which are not captioned, provide a valuable and interesting commentary on the text.

The author (page 18) states rather ponderously that her “study aims to expose the tensions and frictions that occur at the intersection between domestic ideologies and practices.” She notes (page 20) that “Japanese homes are highly gendered.” Such sociological jargon, as in these simple examples and in the outlines of the chapters, quoted below, is likely to appeal more to the academic sociologist than to the ordinary reader.

Chapter 1 “focuses on how inter-family relationships are shaped inside the home.” Chapter 2 “examines the social and spatial connections between the inhabitants and their surroundings.” Chapter 3 examines “the complex domestic spiritual technology consisting of domestic altars, auspicious material culture and graves that is thought to protect the domestic against malevolent influences.” Chapter 4 dissects “the stereotype of the minimal Japanese house” typified by tatami, shōji, tokonoma. Chapter 5 deals with “ordering practices in domestic spaces in everyday use particularly highlighting the dialectic relations between display and storage.” Chapter 6 examines “anxieties regarding the disposal of large numbers of objects that are kept in storage and on display in Japanese homes.”

There are some eye-catching headings such as “we would rather have a nice English garden” and “everyone needs a garage” – (in Tokyo before you can own a car you must prove that you have the space to keep it off the road). We tend to think of Japanese life as much more communal than ours, but Inge Daniels emphasises “the dearth of neighbourly contact.” “Those living in apartment blocks seem to have the least contact with their neighbours.” She also draws attention to the tension between generations.

The following photographs show how traditional Japanese elements in the home are married not always aesthetically with western elements:

We always wondered what Japanese did with their mountains of photographs and souvenirs! Despite Japanese aesthetics emphasising restraint, Japanese may have even more of a problem than we have in dealing with the clutter of modern life.

This book might more appropriately have been called “The Japanese Home” rather than “The Japanese House.”