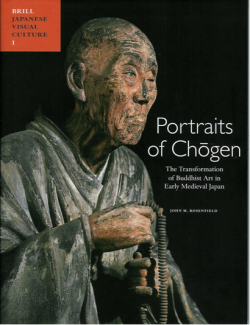

Portraits of Chōgen, The Transformation of Buddhist Art in early Medieval Japan

by John M. Rosenfield, Brill, Leiden, 2010 (Volume 1 in series of books about Japanese Visual Culture edited by John Carpenter) 296 pages including appendices, notes, bibliography and index, copious illustrations in colour and black and white, ISBN 9789004168640

Review by Sir Hugh Cortazzi

The title of this book gives only a hint of the scope of this masterly study. It focuses on the life and work of the Buddhist priest Chōgen重源(1121-1206). It covers the development of portraiture in East Asia and the revival of realism. It then describes the Great Buddha of Tōdaiji 東大寺and the efforts to rebuild the temple after its destruction in 1180 in the war between the Minamoto 源and the Taira平 clans. The development of Buddhist sculpture in Nara and Kyoto is described together with an analysis of the methods used. This is accompanied by an account of some of the leading sculptors. A chapter on icons, rituals and paths to salvation and another on relics and ritual implements provide valuable insight into the various strands of Buddhism in the twelfth century. These are followed by a chapter on Buddhist paintings and illuminated sutras. The final chapter consists of an annotated translation of Chōgen’s memoir. The appendices include notes on Buddhist doctrine and ritual as well as short biographies of some of the leading figures with whom Chōgen was associated as well as a valuable list of characters.

Chōgen was born in the Heian capital, now Kyoto into the Ki family, made famous by the poet Ki no Tsurayuki 紀貫之 whose preface to the Kokinshū 古今集is, to quote Professor Rosenfield, “a foundation document of Japanese literary aesthetics.” He was thus “born into the middle levels of an elite court society.” At the age of 13 he entered religious life at Daigoji 醍醐寺”a vast monastery in the verdant hills south-east of the Heian capital” where he began to study esoteric Buddhism of the Shingon 眞言school and was taught to meditate on mandalas and perform various Buddhist rituals. By the age of thirty-five Chōgen had gained the status of Master Priest. Daigoji was a major centre of ritual mountain climbing and asceticism and Chōgen seems to have been an enthusiastic participant in various austerities especially at the Shingon complex of temples on Mt Koya高野山. He became an itinerant monk (hijiri聖). His reputation as a holy man came to the attention of the court and following the destruction in 1180 of the great Nara temples of Tōdaiji 東大寺and Kōfukuji興福寺, he was appointed as “Solicitor for the rebuilding of the Great Buddha” at Nara and this became the focus of the rest of his life. He was also instrumental in the building of some seven special sanctuaries or bessho 別所for hijiri in which a number of important works of art came to be located. For the rebuilding of Tōdaiji he travelled to Suō周防 province in western Honshu (now Yamaguchi 山口prefecture) to find suitable cypress trees for the temple. These had to be cut down, floated to the sea and transported to the Yodo 淀River for delivery to Nara. One hundred and fifty timbers were eventually brought to Nara. This was a huge task which took two years and involved one to two thousand workmen. Chōgen in later life became associated with the ‘Pure Land’ school of Buddhism which emphasized the role of Amitabha (Amida 阿弥陀) Buddha. He lived to see the completion of the Daibutsuden precinct at Tōdaiji in 1203.

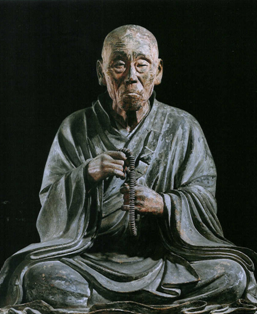

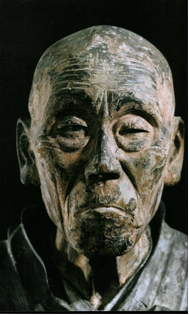

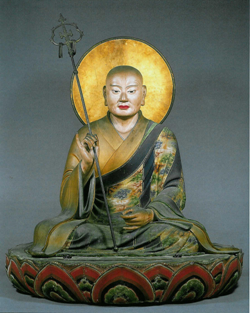

Chōgen was an ascetic with a determined character. This is apparent from the striking facial features reflected in the portrait on the cover of this book which includes a number of fine illustrations of statues of him. The following two photographs from different angles are of the same statue, made in 1206 shortly before he died. The right hand image is a close up view of his face.

Professor Rosenfield in his account of the development of portrait sculpture in Japan shows that while portraits of Chōgen were particularly fine examples of Japanese realism there was a long tradition of depicting prominent persons especially holy men. The oldest extant image in East Asia is that of the Chinese monk Ganjin鑑真 in Tōshōdaiji 唐招提寺 in Nara. Rosenfield describes this statue as “rather artless and straightforward” in comparison with the much later portraits of Chōgen:

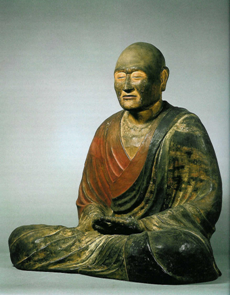

The early eleventh century statue of Rōben 浪辯, one of Chōgen’s venerable predecessors at Tōdaiji, is another impressive portrait. The head and trunk were carved from a solid block of hinoki檜 cypress. As it was kept hidden for a long time it is particularly well preserved.

Another striking portrait sculpture of 1201 which Professor Rosenfield illustrates is that of Hachiman Bosatsu 八幡菩薩at Tōdaiji, a reminder of the way in which Shinto deities (in this case of the god of war) were absorbed into the Buddhist pantheon.

Professor Rosenfield demonstrates that the production of Buddhist images and portrait sculpture were similar arts. He takes as his first example and as a forerunner of the Great Buddha of Nara that of the seated Buddha in bronze of about 742 in the little visited temple of Kanimanji 蟹満寺in Kyoto.

Rosenfield describes this image, despite the ravages of time, as retaining “powerful aesthetic impact.”

It is not possible in a short review to give an outline of the development of Japanese Buddhist sculpture or to do justice to Professor Rosenfield’s scholarship, but the following, which are some of the examples which Professor Rosenfield illustrates, will, I hope, tempt readers to get hold of a copy of the book.

Amida by Jōchō 定朝of about 1053 in the Byōdōin 平 等 院 at Uji宇治.

Amida statues from the mid 12th century in Jōruji 浄瑠璃寺 a temple in southern Kyoto near to Nara.

The series of statues of Kannon 観音 from the workshop of Tankei 湛 慶dating from the 12th-13th centuries in the Sanjūsangendō 三十三間堂in Kyoto.

The Amida from the Amida triad by Kaikei 快慶of 1195 at Jōdōji 浄土寺in Hyōgo 兵庫prefecture.

And as an example of power we might cite the fearsome west guardian of 1203 in the gateway to Tōdaiji by Unkei 運慶.

Students of Japanese art will want to study this magnificently illustrated and fascinating book.