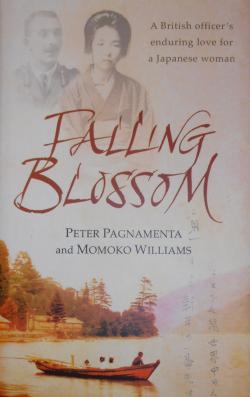

Falling Blossom: A British Officer’s Enduring Love for a Japanese Woman

By Peter Pagnamenta and Momoko Williams, Century, (Random House Group), 2006, 314 pages including notes and acknowledgements, £12.99, ISBN 9781844138203 and ISBN 1844138208

Review by Sean Curtin

The central focus of this well written, moving and excellently researched book is the decades-long relationship between a British Army officer, Captain Arthur Hart Synnot, and a Japanese woman, Masa Suzuki, spanning the early 1900s up to the 1940s. One of the subplots of this gripping narrative is the lives of their two children, Hideo and Kiyoshi. Hideo died during childhood, while Kiyoshi grew to manhood and was eventually posted to Manchuria. His tragic story is a typical example of the fate of countless Japanese captured by the Soviets in Manchuria and the meaningless waste of precious human life. It also illustrates the incredible hardships these men endured.

Kiyoshi was a bright young boy and managed to pass the entrance exam for the prestigious Kyoto Imperial University in 1925. He studied law for four years. His student status meant he was able to defer compulsory military service which all twenty year olds were normally obliged to do. After he completed his studies he moved back to Tokyo to be with his mother and enrolled in a postgraduate course at Tokyo University, studying philosophy. This enabled him to yet again postpone his military service. In 1935, he was awarded a French government scholarship which meant he could go to study philosophy at Sorbonne in Paris. Kiyoshi’s French was already very good and the scholarship gave him an opportunity to study in France for four years. It further extended the deferment of military service. He immersed himself in his studies and appears to have enjoyed Paris life. While outside Japan, anti-democratic, ultra-nationalists were getting the upper hand in Tokyo, setting the country on the path to war. He returned to Japan in 1939, shortly after having a brief reunion with his British father in Lyon. It was the first time the two had met in 25 years.

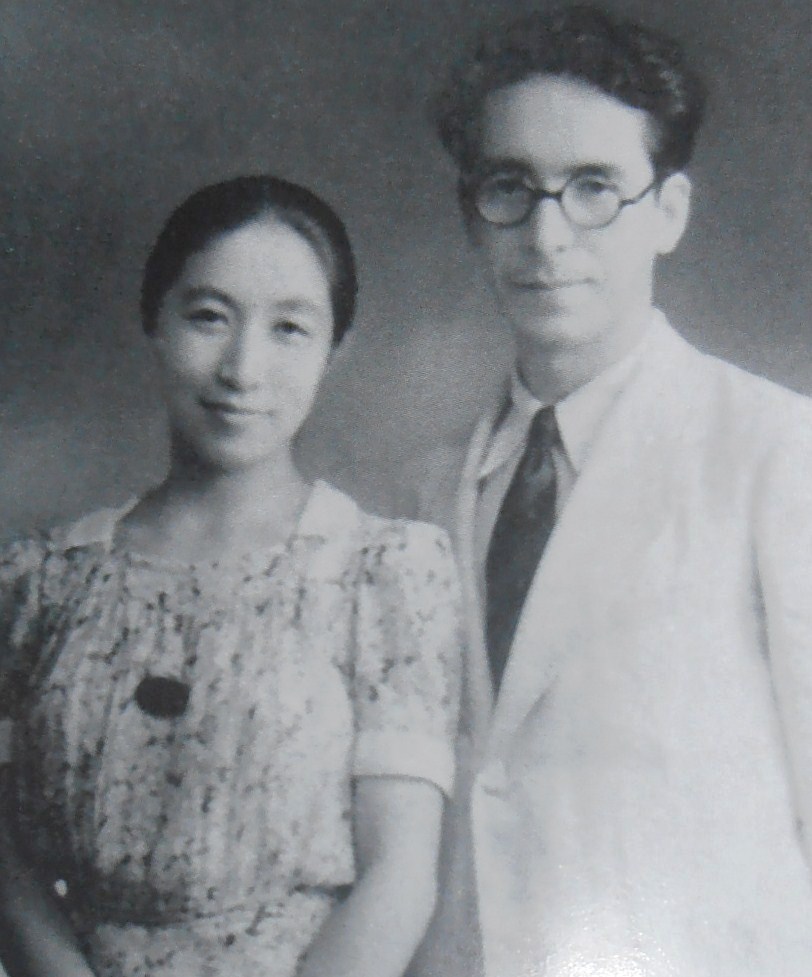

Kiyoshi Suzuki, and his fiancé Tetsuko Katsuda, after his return from Paris in 1939

Upon returning to Japan, he went back to Tokyo University before getting a fulltime job with the overseas branch of the state radio service NHK. This allowed him to use his language skills and the salary meant he could afford to marry his long-standing girlfriend Tetsuko Katsuda. However, the shadow of war was looming and in July 1941 he was called up for military service and ordered to report to the 10th Heavy Field Artillery Regiment at Ichikawa to the west of Tokyo.

At the age of 34, he was thrown into military life and after only a few weeks training was posted to China. He first arrived in Mukden, present day Shenyang (沈阳), the capital of Japanese Manchuria (満州国). He was then posted to the small town of Kairyu (海龍) not far from Mukden. As tensions between Japan, Great Britain and the United States ratcheted up and General Hideki Tojo became Prime Minister, Kiyoshi was posted to Muling (穆棱), a city not far from the Soviet border.

In 1943 Kiyoshi was selected as a suitable candidate to study Russian and sent to a military interpreter school in Harbin (哈尔滨). A year later in 1944, after having mastered Russian, he returned to his unit as the tide of war began to turn against Japan. A few days after the US dropped nuclear bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan, ceasing the Northern Territories off Hokkaido and invading Manchuria. At the time of the invasion Kiyoshi was working as an interpreter attached to a railway regiment defending the Southern Manchurian Railways Company (南満州鉄道株式会社). He was caught up in fighting with the Soviet army, but the surrender broadcast made by Emperor Hirohito on 15 August 1945 led to his regiment surrendering to the Soviets.

At least 600,000 Japanese troops became Russian prisoners of war. Kiyoshi and his fellow soldiers were kept in camps for a few weeks before being shipped off by rail to the port of Vladivostok in the Soviet Union. From there they were moved a further 800 miles by train to Siberia. “To the Russians the Japanese prisoners were war booty” and were “a pool of educated labour to put to work in mines, factories and forests (page 297).”

The highly talented Kiyoshi and a group of about 500 POWs ended up in the mining town of Raychikhinsk and were housed in cattle sheds with earth floors. Despite the bitter cold and little shelter they were only dressed in summer uniforms. Their first task was to build their own labour camp, which was hard in the cold temperate with meagre rations of millet porridge twice a day. As the temperature continued to drop, the harsh labour and malnutrition began to take its toll with several men dying every day from dysentery and exhaustion.

After catching a fever, Kiyoshi was taken to a military hospital in Zavitinsk. The conditions at the hospital were very basic with little medicine. Kiyoshi acted as a translator for the Russian doctors and nurses and the Japanese POWs. His condition did not improve and he died weak and emaciated on 24 December 1945, having just reached the age of 39. Just before he died, he asked a friend, Tojo Yamanaka, to take a message back to his wife, Tetsuko and to thank his mother, Masa. Yamanaka survived and was repatriated to Japan in 1947, informing Tetsuko of Kiyoshi’s fate, but Masa was never told. Tetsuko feared that knowing of her only remaining son’s death would be too much for her to take. Masa eventually passed away in 1965. While Kiyoshi’s story is a sub-strand to the central narrative of this superb book, it is illustrative of the fate of a great many Japanese captured in Manchuria at the end of the war (see another Review of Falling Blossom in issue 4).

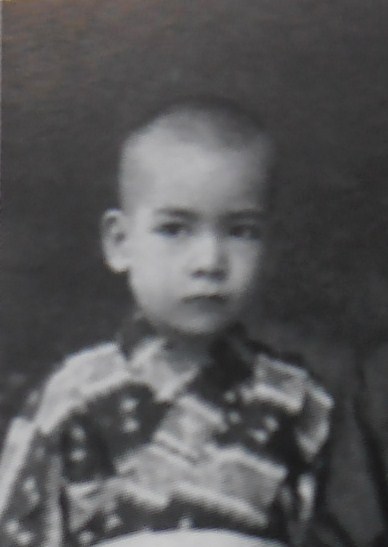

Hideo Suzuki, who died young, in about 1914.