Under Eagle Eyes: Lithographs, Drawings & Photographs from the Prussian Expedition to Japan, 1860-61

Review by : Sir Hugh Cortazzi

This copiously illustrated book has been produced to mark 150 years of friendship between Germany and Japan. Dr. Volker Stanzel, the German ambassador in Tokyo, in his message at the beginning notes that many of the materials collected in this book were long presumed to have been lost. His hope that they will give an insight into the impressions of Japan formed by the Prussian Expedition to Japan in 1860-61 should be fulfilled.

The book after an introduction by the two editors consists of a series of essays and copious illustrations. The first essay is a survey of 150 years of Japanese-German relations. This is followed by an account of the Eulenberg Expedition to Japan by the German scholar Peter Panzer and by essays on Prussian knowledge of East Asia in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, on the German scientist Alexander von Humboldt in Japan and on the rival artists/photographers to the expedition Wilhelm Heine and Albert Berg. These essays are followed by reproductions of thirty lithographs of views of Japan made by the expedition as well as of numerous photographs and lithographs of Japan made by Wilhelm Heine, John Wilson, Carl Bismarck and others.

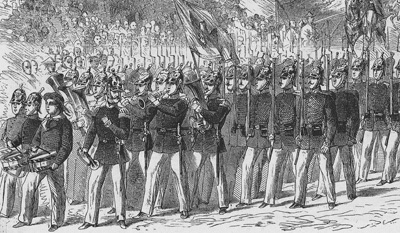

Prussia was not one of the five powers (United States, Netherlands, Britain, Russia and France) who concluded treaties of commerce with the Shogunate in 1858, but the Prussians were not far behind. On 4 September 1860 two ships carrying Count zu Eulenburg and his staff anchored in Edo bay (Eulenburg’s flagship was the armoured corvette S.M.S. Arcon’ of the Prussian navy). They were assigned temporary quarters in Akabane in what is now Azabu in Tokyo. His task was to conclude a treaty of friendship and commerce on behalf of the member states of the German Customs Union which included Prussia, the Grand Duchies of Mecklenburg-Schwerin and Mecklenburg-Strelitz as well as the Hanseatic cities of Lűbeck, Bremen and Hamburg. This objective “was to be secured primarily by means of a demonstration of Prussian military strength.” The two armoured ships did not, of course, pose a military threat to Japan, but were an “unequivocal signal” that the Prussians meant to have their way. The following engraving from the volume reflects the Prussian “show of force:”

In the event, however, faced with Japanese opposition Eulenburg had to abandon the idea of concluding a treaty on behalf of thirty-odd German states and content himself with signing a treaty between Prussia and Japan. (In 1871 following the unification of Germany and the French defeat in the Franco-Prussian war this treaty was extended to the whole of Germany). The Japanese refused to accept the joint letter addressed to the “Emperor of Japan” from the three Hanseatic cities. It was returned unopened, perhaps because it came from people who proclaimed themselves to be merchants who ranked lowest in the Japanese hierarchy.

But the mission had more than just political and commercial aims. It was a well-equipped scientific expedition and included experts in the fields of botany, biology and geology as well as artists and photographers. The secretary of the legation Pieschel, as well as Heine and Berg were “enthusiastic advocates of Alexander von Humboldt’s concept of universal science.” “However, with the possible exception of the exotic animals which the expedition brought back to Berlin zoo, most of the scientific findings failed to reach a wider audience (page 101).”

Many of the illustrations in this book shed a new light on what Edo and Nagasaki were like 150 years ago. Heine’s panorama of Edo in oils on pages 178 and 179 is unfortunately not reproduced sufficiently clearly, but many of the lithographs of Edo such as that showing the main north gateway to Edo castle (page 215) and the Tōkaidō near Nihonbashi (page 229 and reproduced on the cover) are fascinating. The artists/photographers seem from the selection of illustrations to have had a fixation with grave yards as so many of these seem to have been depicted by them. The juxtaposition of photographs and the subsequent lithograph is helpful as it shows both what was lost and what was gained in the process.

This is a valuable addition to the literature about the reopening of Japan in the mid-nineteenth century and fills a gap in the material easily available in English about the German part in this development, but the oblong format of the book does make it a little awkward to hold and read.

Additionally, the use of parallel texts in German, English and Japanese enables students, not proficient in German or Japanese, to access without linguistic problems the material in this volume [ – those readers familiar with both German and Japanese who wants to check the original sources, especially against their English translations, will also find this useful].