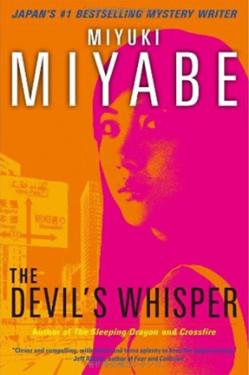

The Devil’s Whisper

The Devil’s Whisper [魔術はささやく], By Miyuki Miyabe [宮部 みゆき], translated by Deborah Stuhr Iwabuchi, Kodansha International, 2007 (originally published in 1989, Tokyo), 264 pages, £8.99, ISBN 4770031173

Review by Michael Sullivan

Miyuki Miyabe was born in 1960 in Tokyo, she has been writing since the 1980s and a number of her books have been adapted into dramas and films in Japan. For example, just last year her 1992 novel Kasha [火車] was released as a TV movie starring Takaya Kamikawa [上川 隆也]. Although her work touches upon a number of genres, it is often quite firmly classed as mystery, and The Devil’s Whisper has a very puzzling plot. In particular there is a strong element focusing on guilt and secrets, whether the feeling is acknowledged or not, all of the characters strive to repress it. However, as this book develops the discovery is made that guilt will eventually catch up. Only since 1999 have Miyabe’s novels started to be translated into English, though only a handful so far and as such represents the burgeoning interest in Japanese literature that was sparked by other novelists such as Haruki Murakami.

Mamoru Kusaka is a sixteen year old boy, and yet despite a turbulent childhood he is very cool headed and practical. When he was a small child his father was embroiled in an embezzlement scandal, one day he left home and never returned. His mother refused to believe he wouldn’t return and so, ostracised by the local people, they lived on in the same town until his mother died. Now living with his aunt, uncle and cousin in Tokyo, Mamoru attends a local school and works part time at a book shop. His new family clearly dote upon him, but Mamoru’s life is again turned upside down when his taxi driver uncle is arrested under suspicion of running a red light and killing a young female pedestrian. With no witnesses, time running out for his uncle, bullies at school who seize upon this opportunity to make his life difficult, and strange phone calls to his house, Mamoru decides to investigate this accident himself and in the process finds out that this was no ordinary accident.

As his investigation progresses, strange things begin to happen at his book shop, a man goes berserk and a young girl becomes suicidal, and he discovers about some other apparent suicides that seem to have a connection with the girl who ran in front of his uncle’s car. A lucky break appears when a mysterious, and rich, middle aged businessman claims to have witnessed the car accident and exonerates Mamoru’s uncle from blame. However, this businessman seems to have an agenda of his own that he is following, and clearly knows secrets pertaining to Mamoru’s troubled past.

This novel maintains a fast pace and it is easy to become totally engrossed in the plot and lose track of time. Miyabe weaves a very intricate story where it is easy to make suppositions about the truth, and be surprised when she pulls apart those suppositions. As mentioned before, there is a strong element of guilt pervading all of the characters, but the guilt is clouded by justifications that they have nothing to be guilty about. Ultimately, they are all shown that no matter what they are guilty of, guilt has a way to pursue them.