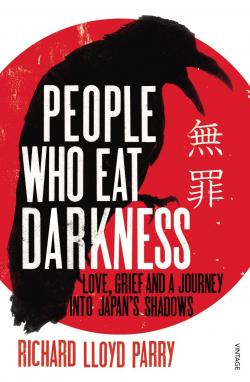

People Who Eat Darkness – An interview with Richard Lloyd Parry

‘People Who Eat Darkness’ – An interview with Richard Lloyd Parry

Article by Michael Sullivan

On July 1st 2000 Lucie Blackman went missing in Tokyo, months later her body would be found, dismembered, buried under a bath tub in a seaside cave in Miura, Kanagawa. The period of time leading up to that discovery would stir up a controversy as reporters questioned what exactly she was doing in Japan while her family desperately wanted to find out where she was. At the same time strange phone calls and letters would claim that she had joined a cult and did not want to be found, while the description of Lucie’s last phone calls would stir up unpleasant memories for a number of young women. She had been on a “douhan” (paid date), she was being driven to the seaside and she was going to get a mobile phone and free drinks.

The recollections of these women, of being taken to a seaside apartment and waking up the next day feeling unwell and confused, would eventually lead the police to Joji Obara. What followed next almost stretches belief. The police discovered large amounts of evidence in one of Obara’s flat, videos of girl after girl unconscious in his bed as well as the last known photos of Lucie, yet he would never admit any guilt for doing anything wrong.

In October 2000 he was arrested, following a trial that lasted years. In April 2007, he would be found guilty on multiple rape charges and a manslaughter charge for the death of another hostess ten years earlier. Finally in December 2008, he would be found guilty for the abduction of Lucie, and the dismemberment and disposal of her body, but not for her murder.

From the beginning to the end he argued continuously that he was innocent. Meanwhile Lucie’s family struggled to get through long years of searching for an answer to why this had happened to their beloved daughter and sister.

Richard Lloyd Parry followed this case from start to end and his book presents a mind detailed with knowledge about every single person who was affected by this tragedy. It is a compelling book and it restores Lucie from being someone who was killed to a complex and loving individual. I, and the Japan Society Review editor Sean Curtin, were lucky enough to have a chance to sit down with Mr Parry and discuss his book.

Q: Why do you think in the appeal (2008) that Obara was found guilty? Was there any change in evidence or did something come up in the appeal that they hadn’t considered before?

Richard Lloyd Parry: The prosecutors put their arguments better. The trial had gone on for so long, the Tokyo prosecutor’s office was like any branch of the Japanese civil service; people changed jobs over the years. The prosecutors changed over the course of the trial and that was something that Tim (Lucie’s father) was upset about. He felt there was a lack of co-ordination on the part of the prosecutor. For example, among other things the prosecutors drew attention to the fact that flunitrazepam (rohypnol) had been found in Lucie’s remains. The remains had been in the cave for so long, it was difficult to establish cause of death and things like chloroform don’t linger in tissue for long enough. So she may or may not have been chloroformed, there is no way of telling, but they did find traces of flunitrazepam and as Tim said she didn’t date rape drug herself, someone did that. They found flunitrazepam amongst Obara’s possessions, so I think that the reason the appeal judges took a different view was that the prosecutors had presented the case more persuasively.

Q: From my knowledge the lower courts tend to err on the side of caution and be conservative, while you have to go to the higher courts for a bolder decision as they seem to have a little more leeway. Could that have affected the different judgements, or do you think it is just primarily a better presented appeals case?

RLP: It may be broadly true, in both the district court and the appeal court, both of the judges made a point of saying it’s not that we think he (Obara) had nothing to do with it, it’s just that it hasn’t been proved. As I say in some length in this book we often think of Japanese courts as being terribly tough, over 99% of defendants who walk in there don’t leave through the front door. Normally they confess and it’s extremely unusual for prosecutors to go forward with a case that doesn’t have a clear cut confession, and judges feel very uneasy convicting without a confession. So when there isn’t a confession, defence lawyers have much greater scope in doing their jobs successfully.

Q: I was thinking that the problem with Japan is that 99% of the people fall into the matrix of society, but it’s the people like Obara who don’t follow the rules, who don’t confess, where the system breaks down. So, someone can do, like he did, for several decades and get away with it, because the nature of Obara himself is so removed from mainstream society. He convincingly pretends to be a participant while being outside it. Do you think he realised that himself and thought he could get away with it? Does this explain his own defence that the girls were drug-taking prostitutes and he wasn’t doing anything wrong?

RLP: At one point in the book I talk about the police, that it was quite interesting talking to them about the case. Because, you could ask them about Obara and they would shake their heads. He was so unusual, so difficult, it was almost as if the police felt sorry for themselves and they felt that they themselves were the victims of a colossal piece of bad luck; which is a dishonest criminal, a criminal who doesn’t do the right thing and doesn’t confess, because most Japanese do. Even the hard cases do.

Q: Regarding the crimes of Obara, besides the fact that he has argued that he has done nothing wrong, you also wrote that Obara’s brother said “what do you expect to happen if a girl enters a man’s apartment?” Despite Japan being such a safe country, I got the impression from your book that there is almost a sense of it being the victim’s fault for going into the wrong apartment?

RLP: Yes, I mean, the police then and I think still now are disinclined to take seriously reports of sexual assault from hostesses, from mizu shobai girls [mizu shobai is the traditional euphemism for the night-time entertainment business in Japan], and foreign girls. There seems to be a sense, and I am generalizing, that if you work in that world basically using your charms to make money off men, then you are taking risks and certainly if you go back to a guy’s place and he has sex with you, then the attitude is “you consented to it when you walked through the door, didn’t you? What were you thinking?” It is a very old fashioned, certainly to us, attitude. To many Japanese it is an old fashioned attitude, but that was the attitude. So when a small number of these female victims found the confidence, could recollect what had happened to them, and went to the police to try to make a complaint, the police were uninterested.

Q: I noticed in the book that you give the example of Yuki Takahashi who always attended the hearings, and she said that she liked Obara. She also liked the prosecutor, observing he was cool and her type. Do you think that for many Japanese people the whole situation was too unreal? For example, here is a man who has done so many bad things and won’t admit to it throughout this drawn out trial, so for some it became surreal and difficult to realise that any crime had happened?

RLP: I don’t think Yuki Takahashi is typical of many Japanese people, but it’s a feature of the public trials in Japan that eccentrics attend. I have been to a lot, more than in the UK, and anyone can turn up for a public trial. You just sit yourself down, there is nothing to stop people going, but somehow to most Japanese it is something they would never think of doing unless they were law students or “court otaku.” She is an otaku (nerd), for her and her girlfriends it was just a hobby to go to these trials and write it up in their blog. Like a lot of otaku their enthusiasm for the overall subject isn’t a very discriminating one, they are excited by everything about it. Rather than going in there with a view to drawing moral conclusions about right and wrong, they went there for the excitement and that is reflected in the way I wrote about Yuki. I spent a lot of time looking around at the other faces in the gallery, and there was a funny crowd. You get some people who look as if they are basically there to keep out of the cold, like borderline homeless, you get some who are clearly law students that take notes and familiarise themselves with the court. And then, you get some really quite eccentric people, including her. There was also one chap called the Mighty Aso who wore a green skirt, he had a blog as well. He would sometimes turn up in a chequered skirt and green hair. He was at the extreme end of the odd factor. A lot of people looked a bit strange, were atypical, and didn’t tell you very much about the attitude or disposition of Japanese people in general.

Q: In regards to Obara himself, do you think there is any chance he will ever admit some form of guilt for what he has done?

RLP: I don’t know is the only honest answer I can give. My sense of Obara is that he was determined to prove himself not guilty and to escape legal penalty. Now that battle has been lost, his legal avenues have shrunk; I have wondered whether he might make some kind of confession because he hoped that would help him in future parole proceedings. Obviously at some point, not soon but eventually, he will be eligible to apply for early release. I don’t know the Japanese parole system very clearly. I know in the UK the extent to which you are penitent and take responsibility for the crimes of which you have been convicted influences whether you are let out early or not, so it wouldn’t surprise me if at some point he said “I am sorry, I did the wrong thing,” and that might help him get out.

Q: I was struck how Obara seemed to have no friends, no one seemed to know him, and you mention in your book how he had several businesses. How did he conduct those businesses? Did he keep a distance between himself and his employees and associates? Or, would just no one talk about him?

RLP: What I know with certainty is in the book, I haven’t held back anything I can prove, there is a lot of stuff I heard which I can’t prove. I spent a lot of time researching Obara and his background, I could have spent more but it was really yielding diminishing returns. So I decided to stop and go with what I had. You are right; he did have people working for him. For example, at one point he was running a ramen restaurant in Ginza, we found the place but the restaurant had closed and no one knew what had happened to the employees. I would have loved to interview Obara’s ramen chef, but my investigations just came to a dead end. By the time he was identified and was charged, he was close to going personally bankrupt. He declared himself bankrupt within two years of the trial, some of the companies were transferred to other members of his family, and others were just wound up by a bankruptcy authority. So, there weren’t really companies to go to. On company documents we found addresses, but either the company didn’t exist anymore or you got there and they were just postal addresses.

Q: I noticed that in your book you mention that some people were listed as members of the board of a company, but they didn’t even know they were part of that company as he had just put their names down.

RLP: Apparently, yes, that was reported. There was one company which had the name of one of his relatives, I think a cousin, who we tracked down in Nara and this man ran a sake shop. We went in there and introduced ourselves, and well he wouldn’t say anything. So it was very difficult to pursue that kind of enquiry.

Q: I was drawn to the fact that Obara’s heritage is Korean. When we look deeper into his character and why he did it – it is difficult because he is something of a blank – we have to try to construct a lot ourselves. Presumably his ethnic heritage is an element in his sense of identity? It seems that quite a number of Koreans in Japan tend to conceal their heritage while Obara appears to demonstrate an extreme form of this trait by wanting to conceal everything about himself.

RLP: There is a chapter about his Korean background and the history of Koreans in Japan, their story is fascinating and very little is known. They are such a huge diaspora, but their history there is so little known, even in Japan. There are lots of things about what we know about Obara and his upbringing which might have disturbed his sense of identity. One is being the child of immigrants, also I think, as important as that, is that he went from the child of poor immigrants to being the child of very rich immigrants. So they were displaced by the Korean slum in Osaka to Kitabatake which is one of the poshest places in Japan. There was that displacement, there was the displacement of his education, and he left his family and went to Tokyo to go to Keio University. As a seventeen year old he had basically gone to live on his own in a playboy mansion. Then there was the death of his father when he was quite young, whatever that was about – we still don’t know what killed his father. He changed his name, he changed his nationality, changed his face, so you can look at all of those and think well no wonder he had issues. On the other hand there are millions of spoilt rich kids, millions of kids whose fathers went from poor to rich, millions of people who have issues about their appearance, their eyes, and only one Joji Obara. So, it just doesn’t add up to what he became.

Q: Regarding the book itself, this case went on for years and years, was there a trigger moment when you decided to bring together all of your research and make it into a book?

RLP: There probably was, I started reporting the case for the Independent, which I was working for in 2000 when Lucie disappeared. This was obviously a story of interest for a British newspaper; a young British woman who had disappeared in Japan. It was an intriguing story, very far from straightforward, which had no early conclusion. I think it was after the trial began that I came to realise that it would make a good book, because that was when we got a good glimpse of Joji Obara. Although it took a long time for me to get to grips with him and understand what an extraordinary man he was. But it was straight from the beginning that it became apparent he was very unusual and very strange. So, it was probably as the trial was getting underway that the idea was formed.

Q: By then had you already got most of the material for the book or was there still a lot of research to do?

RLP: There was a lot to do. I was actually writing another book at that time about Indonesia, Lucie disappeared in 2000 and the trial got underway in 2001, and until 2005 I was writing another book. So I didn’t start working on it as a book until around 2006, but I was gathering material and keeping everything, and making sure that my assistants were taking comprehensive notes in the court hearings as I had it in mind that it would be useful one day.

Q: When the book actually came out, how did the (Blackman) family react to the book? Did they read it before it was published?

RLP: They got copies before it came out, of course they were amongst the earliest people to be sent copies. Sophie Blackman, the sister, was very supportive. She said she liked the book and thanked me for it, she helped to promote it actually, and we did some radio together a year ago when the hardback was published. Tim and Jane (Lucie’s parents), I haven’t had long conversations with them about it since then, but in different ways they both felt at least slightly that it was biased to the other person. Rupert (Lucie’s brother), I don’t know. He was sent a copy, but I don’t know if he read it or not. That is up to him, but I can understand why someone in his situation may not want to. I am still in touch with them intermittently, but I have been trying to leave them alone. I spent quite a lot of time with them intensively, though I hope to remain friends with them and keep in touch, but I don’t want to overdo it.

Q: I have one final question, having read the book I felt you have painted a very compassionate and full picture of Lucie, such as the information you got from her parents and sister, and obviously you studied the case for a long time. I think from the way you write that you feel that you got to know Lucie well. Do you feel in any way that some of your objectivity was lost, as you yourself were drawn into the narrative? Do you feel that this has impacted on your life as well?

RLP: It certainly had an effect on my own life, I got to know the family well and I spent long hours talking to them about unbearable things for any parents to experience. And those interviews were often very emotional and tears were shed. I tried to be a sympathetic listener, and I felt very sad, very sorry for them. It would be ridiculous to exaggerate my own emotional sufferings; I was emotionally involved to an extent that I felt very sorry for these people who I cared for. I felt sad seeing a mother weep for her dead daughter. Jane Blackman lost her daughter and will always struggle with that a lot. I had a job to do, and I think an important job, to get the story down and get it right, to tell the story in all its complexity. So, objectivity was the absolute goal and I hope I did preserve that. When I first went to see them, Jane and Tim, it was probably in 2006 or around then, I said to them I want to do this book, I want to know a lot about Lucie, and about what happened in Japan. I said I also want to know a bit about you, but I am not really that interested in your differences, as their marriage had gone bad before Lucie even went to Japan. I said I’m not so interested in that, it has to be mentioned of course, but it’s not what the book is about, however a few years later that was no longer true. The relationship between Tim and Jane had become a central part of the story because of the issue of the blood money. I was in a situation where I was writing about a bad marriage, now all of us who know people who’ve had bad marriages know how hard it is to remain on good terms with both sides. You can only really do that if you achieve a certain amount of detachment, and you make that clear to both parties. If you make that clear and don’t pretend anything else, then it is possible. I hope I was honest with them both, which is what I have tried to be.

Language notes:

Douhan – 同伴

Mizu shobai – 水商売

Kitabatake – 北畠