Obtaining Images – Art Production and Display in Edo Japan

by Timon Screech

Redaktion Books (published with the assistance of The Japan Foundation), London (May 2012)

384 pages including glossary, chronology, references, bibliography, acknowledgements and index, copious colour illustrations

ISBN 978 186189 8142

Review by Sir Hugh Cortazzi

Professor Timon Screech is Professor in the History of Art at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London, and is a Japanese art expert who has made a particular study of the art of Tokugawa Japan.

Obtaining Images is a scholarly study of painting in the Edo or Tokugawa period. During the two and a half centuries between the beginning of the seventeenth century and the re-opening of Japan to the West shortly after the middle of the nineteenth century Japanese artists produced paintings which are among the finest anywhere in the world. Screech’s book not only analyses the factors which influenced Japanese artists but also provides a historical survey of the large number of different styles and schools of Japanese painting. It is full of fascinating insights and will be invaluable to all who want to know more about and understand Japanese art at its apogee.

In his introduction Screech reminds his readers that paintings were not only important for their visual impact. They also reflected the status of their owners and of the painters themselves. Screech accordingly devotes the first part of his book to a discussion of ‘the mechanisms of artistic production and display.’

His first chapter is entitled Legends of the Artists in which, among other legends, he exposes the myth of the ‘Superlative Painter.’ Chapter Two entitled Auspicious Images reviews the traditional themes so often found in Japanese paintings such as dragons, kara-shishi (唐獅子- Chinese lions), kirin (麒麟- horse dragon) and the hōō (鳳凰- phoenix). Leopards and tigers were not found in Japan but were depicted for instance in a famous screen by Sanraku Kano [狩野 山楽], where Screech explains that the two animals were regarded as ‘he and she tigers.’

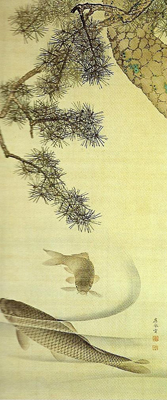

He explains various conceits used by Japanese painters such as those reflected in the two images below:

1. (Left) Mōkari (culling reeds) is a pun on the word mōkaru (儲かる- make money) in this early 19th century painting by Ippō Mori [森一鳳]

2. (Right) Pines (shō [松] is the on reading of matsu (pine) and carp (ri [鯉] is the on reading of koi (carp). The two combined would read shōri [松鯉] which written with different characters mean “victory” [勝利]. Painting by Ōkyo Maruyama [円山 応挙].

The next chapter on buying and selling begins by describing the six standard painting formats – hand scrolls, albums, hanging scrolls (kakemono –掛物) which included diptyches and triptychs, screens which might be single leaf or folding, sliding screens (fusuma –襖) and fans (sensu and uchiwa -扇). Screech goes on to give some fascinating insights into social mores in Tokugawa Japan. He points out that status carried with it obligations when it came to buying and giving away pictures. Some painters e.g. of the Kano school received official salaries and were regarded as the elite. Their ‘ateliers would not entertain commissions from commoners (Page 82).’ ‘Especially prickly were the gentlemen amateurs like Taiga and Buson’ who saw themselves as samurai. As such they could not demean themselves to become involved in commercial transactions.

Screech in the final chapter of part 1 entitled The Power of the Image deals with religious art, which in the Edo period meant Buddhist paintings and images. This enables him to discuss such significant Edo era sculptors as Enku. He notes that a great deal of secular painting was preserved in temples which tended to be better preserved than secular buildings, Some of the finest Kano school screen paintings are indeed to be found today in Kyoto temples such as the Chionin [知恩院] and Nishi Honganji [西本願寺] in Kyoto.

In part two Screech provides an informative survey of the different schools of painting in the Edo period. He starts with an account of the Kano school. He notes that Tan’yū Kano [狩野 探幽] who arrived in Edo in 1622 was given formal military rank and ‘they ran their ateliers with the punctiliousness of all other shogunal officers (page138).’ The Kano school was ‘part of the government.’ They had their own secret text book setting out ‘their ideologies and values, its categories of subject matter, its historical lore and its protocols and pedigrees (page 139).’

The Kano school did not change with the times. They were forbidden to adapt.

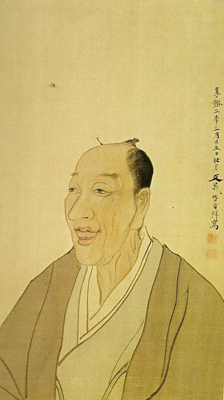

Screech deals next with portraiture where the Japanese approach differed greatly from the European. There was ‘no thirst for portraits of people to whom one was not in some way connected (page 167).’ In Tokugawa Japan visitors to the shogun did not look at him but kept their eyes down to the floor. Portraits tended to be commissioned when an individual was approaching death. They generally showed the sitter ‘looking to the left, that is, their right. The most honoured position was facing south, looking towards the sun and important people routinely sat that way. Since a portrait should be treated like the person, respect demanded it be hung on a north wall.’ It was rare for a portrait to show the sitter other than in a formal posture. Bunchō Tani’s [谷 文晁] posthumous portrait below of Kenkadō Kimura [木村蒹葭堂] which shows him smiling and in the act of talking is an exception to the general practise:

The next chapter is entitled perhaps rather oddly Japanese Painting. It deals firstly with the Tosa school which was associated with the court and ‘concentrated on Heian poems and tales, and the birds and flowers that appear in them.’ Kōetsu, Sōtsu, Kōrin Ogata [尾形光琳] and Hōitsu, often considered members of a separate Rimpa school are covered in separate subsections of this chapter.

Chapter Eight is entitled Painting within the Heart. This covers the literati painters and explains what is meant by nanga (南画- Southern paintings). This style had no geographical connotations, but rather denoted the way in which the painter depicted his subjects. Landscapes and even flowers and trees were not depictions of real scenes but were imaginary from ‘within the breast.’ Within this chapter Screech also covers the Ōkyo Maruyama [円山 応挙] and Shijō schools and Jakuchū Itō [伊藤 若冲].

Chapter nine is entitled Floating World (ukiyo). Screech explains that in the Yoshiwara (red light district) and the theatre, which were central to the ‘floating world,’ the rigid class distinctions of Edo Japan became blurred and the classes mixed. This chapter covers aspects of ukiyo-e, but is not intended as a history of the art of the Japanese print which impressed western observers and artists so much in the nineteenth century. Even so it seems a little odd that such an outstanding artist as Sharaku (Tōshūsai) [東洲斎 写楽] is not mentioned.

The final chapter is devoted to a discussion of artistic contacts with the West where perhaps the most well known Japanese artist who reflected western influences was Kōkan Shiba [司馬 江漢]. His picture of birds in a winter landscape with a western city in the background is shown on the back cover of this volume.

Kōkan Shiba: Birds in a Winter Landscape late 18th century

Western influences also had an impact on ukiyo-e as can be seen in this charming print by Harunobu Suzuki [鈴木 春信] showing a girl looking surprised to see the shadow cast by her umbrella:

In such a lavishly produced book I was surprised that no Japanese characters were included. In the past when type had to be set by hand it was understandable that Japanese characters were eschewed, but there is no difficulty these days in introducing characters into books in English. I would have particularly welcomed the printing of the names of Japanese artists in Japanese characters. They could also have been used beneficially for students with some knowledge of the Japanese language when Japanese poems are quoted.

Screech excuses the fact that his book does not cover calligraphy, but it would in my view have added to the value of this work if it had included even a brief chapter on the great calligraphers of Edo Japan. Calligraphy was such an important feature of Japanese ink painting.

Screech refers briefly to such popular pictures as Otsu-e, but his book is primarily about ‘high art’ and he has not been able to devote space to picture books which became so popular in Edo Japan.

The book does not claim to be a history of Edo art but only of images produced in the Edo period, but the frontiers of art especially in Japan merge so easily that imagery becomes important not merely for lacquer ware, briefly mentioned in the context of Kōrin Ogata (page 223), but also for the hugely important field of Japanese ceramics.

This book is already a lengthy one and it would be wrong to make too much of what it does not cover and indeed does not claim to cover. Every serious student of Japanese art will want to read and to possess a copy of this important and informative book, if only in order to be able to consult it as necessary.