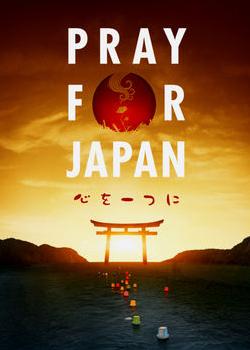

Pray for Japan

Directed by Stu Levy

Pray for Japan Film LLC (2012)

Review by Susan Meehan

The Japan Society organised a special charity screening for the European premiere of Stu Levy’s documentary film, Pray for Japan, at the British Academy for Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) on 14 March 2012.

After the earthquake and tsunami of March 11, Stu Levy volunteered with the Japan Emergency NPO (JEN) in Ishinomaki (a city with a population of over 160,000), Miyagi Prefecture. He shot 40 hours of footage over five weeks, interviewing over 30 people including victims and volunteers. At the time of the earthquake Levy was in Tokyo. The film is an extraordinary snapshot of life in Ishinomaki [石巻市] within days of the earthquake and tsunami.

The film starts by zooming into Ishinomaki, the largest coastal city in north east Japan, as it was prior to the disaster. This footage is beautiful, sharp and exhilarating; we see Ishinomaki’s unspoiled bridge, cherry blossoms and homes by the sea.

Yet more cherry blossoms appear. We are fast-forwarded to the events of March 11 and hear people talking about their hometown. A most poignant comment resonates, “My hometown is everything.”

At the time of the earthquake Kento Ito, a high-school student, was performing with his band in Sendai, and a graduation ceremony at Ogatsu Middle School had not long concluded. Everyone was going about his or her business when the earthquake hit at 2:46pm on 11 March, changing everything.

Levy’s interviewees recall their thoughts at the time. “We thought it was a Tokyo earthquake.” “There was no [phone] reception.” “I thought the whole of Japan was going to sink.” 30 minutes later the destruction of the earthquake was compounded by a devastating tsunami which reached 40 metres in height at places. We see cars and huge containers being washed away, looking like miniature playthings in a child’s bathtub. “We lost it all,” says one of Levy’s interviewees.

The film then breaks into almost psychedelic animation and guitar music, mirroring the viewer’s disbelief and sense of surrealism at the extent of the destruction, the number of people deceased or missing and the thousands of evacuees.

We are exhorted to pray for love, rebirth, dedication, conviction, resilience, leadership, fortitude, the future, hope, the soul, compassion, strength, solidarity, recovery, unity, courage and Japan while beautifully crafted animated pictures are shown on the screen.

The Ishinomaki we now encounter is a ghost of its former self; it has been left wrecked with only piles debris to account for the former homesteads. Homes have been washed away and so has the bridge.

Levy focuses on four themes: shelter, school, family and volunteers, letting the people of Ishinomaki speak for themselves. He keeps returning to each of these items in turn for the remainder of the film. This results in repetition and frustration as no one’s story or viewpoint is ever given enough time or the chance to develop.

About 1,500 people sheltered in a flooded gym and were isolated for three days with no food and only four bottles of water. Priority was given to the dehydrated, the elderly and children while the healthy survived without water for three days. Provisions finally arrived, in the form of 300 rice balls. An impressive Council man reads the “emergency manual” in the gym which says that food must not be distributed until there is enough to share with all evacuees to ensure fairness and that fights don’t break out. These dispossessed individuals wait until they have enough rice balls for everyone to receive “half a portion.” The Council man, extraordinary in his sense of justice and dignified and charming comportment, is an undoubted star of the film and a shining example of humanity to all.

We then shift to Ogatsu Middle School. The graduation ceremony for the Year Six had taken place earlier that afternoon and the kids had been sent home at about 1pm on 11 March. They were all scattered throughout the city when the earthquake and tsunami hit. As the spirited art teacher remarked, had they all been at school at the time of the disaster it is likely that many wouldn’t have survived as school emergency procedures and rigmarole, including roll call, would have delayed evacuation.

The teachers, who feel tremendous responsibility for each of their pupils, went to Ogatsu Shinrin Park and compiled the names of all their pupils from memory. Their next objective was to track down their 77 pupils. By 19 March all pupils had been accounted for, dispersed amongst 17 different evacuation centres.

In an attempt to create a sense of normality and cohesion, the school is relocated to the nearby, apparently empty Iinogawa High School. The pupils derive great comfort from their new base and this decides their families to stay in the area rather than evacuate Tohoku. This is testament to the extraordinary vitality and speedy action of the teachers.

The school motto is changed for the first time in 30 years, the new version comprises the Japanese for “resilience” (たくましく ).

A third focus is the Ito family. Kento, a 17-year old student from Ishinomaki Nishi Senior High School, was rehearsing for a gig in Sendai with his band members when the earthquake struck. Finally back in Ishinomaki, having been stranded in Sendai for two days, he heads to the razed area where his house had stood and begins a quest for his family by visiting the evacuation centres. He is reunited with his father and one of his brothers, but discovers that his adorable five-year old brother Ritsu has died along with his mother and grandparents. They were all at home when the earthquake struck and decided to flee by car. Tragically, this was not to be as they were stuck in traffic when the tsunami claimed their lives.

Amidst the rubble, Kento finds a colourful carp streamer which reminds him of little Ritsu who loved seeing the koi nobori (carp streamers) flying in the wind on Children’s Day, 5 May. Kento manages to gather hundreds of carp streamers sent from well-wishers all around Japan and hoists them up in honour of little Ritsu in time for Children’s Day. This part of the film is particularly harrowing as we see Kento, friends and band members back in the desolation where the Ito’s house had been. They beat Japanese taiko (drums) with a frenzy and passion reflecting their agonising heartbreak. While honouring and perhaps calling the dead, their valiant resolve to keep living despite the overwhelming grief is apparent. Once the drumming is over, lit lanterns, flickering like fireflies, are sent down the river in memory of the dead.

At one of the volunteer emergency centres, two busloads of volunteers from Sendai are arriving every day and three busloads on the weekends. One volunteer says, “There’s no give and take; it’s give, give, give.” It is clear that the longer the volunteers stay in Ishinomaki, the more reluctant they are to leave as they are aware of how much needs to be done. The volunteers selflessly dedicate themselves to their work with impressive panache: cooking, shovelling mud, clearing up debris and generally elevating the spirits of those in the shelters.

As we begin to see early glimmers of hope and a slow return to normality, there is a farewell party for some of the volunteers who are returning home, having been helping since immediately after the earthquake up until April. Many of the volunteers are set to return to Ishinomaki in the near future in order to help once again. For many, Ishinomaki has become their second home.

Levy finishes by asking his interviewees what they expect the situation will be one year on. The answers vary from, “Still in chaos,” to “Lots of debris still,” to “I don’t know” to “I’ve no clear picture” to “The situation won’t be rosy in a year.” Levy himself could have added his own insights at this point or galvanised people to act and help (rather than pray).

It is a pity that the film doesn’t include current information on the situation in Ishinomaki to bring it up to date. With the immediacy of the news, blogs and social media in general, we have all been made aware of the devastation wreaked in Tohoku which has been reported on a global scale. Levy’s film is another reminder of what happened. It would, perhaps, have been helpful to have a perspective on the situation in other parts of Tohoku, not just Ishinomaki, or to have heard about the role of the government or the nuclear accident or speculations about the future of Ishinomaki and Tohoku.

On 12 March an explosion blew apart the building containing reactor 1 at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant, yet no mention of this crisis is made in the film.

Instead of an objective interlocutor, adding useful information not known or available to the interviewees at the time of filming, there is an occasional female voice reading aloud poems in Japanese. This is an unnecessary pretension and somewhat irritating. Along with the animation it was perhaps intended to give the film an artistic dimension, but failed to add anything of positive worth.

The way Levy focused on the shelter, the volunteers, a family and a school was ambitious but the continual tug between the four perspectives resulted in a rather disjointed film. A more in depth look at the volunteers or evacuees or the school alone might have made for an improved film.

While undeniably a powerful film, we could have done with having seen it in May of last year or in the run-up to the first year commemoration of the disaster rather than a year on. For Levy it is important to point out that 900,000 people are still living in shelters and that 650,000 have lost their livelihoods and that entire villages have been destroyed. However, the needs of the evacuees have moved on and we have become aware of different and changing issues through daily updated blogs. Moving into the present doesn’t diminish the horror of what happened a year ago; it, acts in fact, as a means of ensuring that awareness of the situation in Tohoku is ever present.

Levy has produced a good film for an excellent cause. Though I’d exhort everyone to do what they can for the recovery of Tohoku and not to forget this important cause, the film won’t add to what we already know.