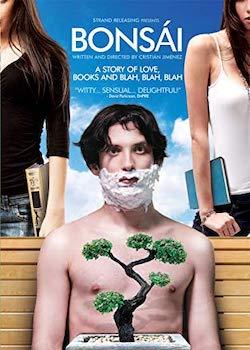

Bonsái

directed by Cristian Jimenez

(Based on the novel, of the same name, by Alejandro Zambra)

2011, Spanish with English subtitles, 95minutes

Review by Susan Meehan

Bonsái is a youthful and whimsical film inspired by literature – Proust looms large. The film flits back and forth spanning a period of eight years; the earlier time centres on the university romance between Julio and Emilia. They live in Valdivia, a city in southern Chile. She is a bright rock chick while he is mild and tender. The film is weighty with melancholic ennui and searching. It won the Films in Progress 19 Award in Toulouse in 2011 and was part of the Official Selection, 2011 Cannes Film Festival.

Though not a Japanese film, the title, of course, is. The director himself, on a tour of Japan, remarked on his film’s ‘Japanese sensibility.’ I went to see it curious about the Japanese dimension. It is not as dark as Norwegian Wood, though from the start we know that, ‘Emilia dies and Julio does not die, the rest is fiction,’ but shares this Japanese film’s grace and freshness.

Bonsái would suit anyone hoping to see something different and fresh and to witness the emergence of young Chilean talent in the form of the director, Cristian Jimenez, and the four main telegenic protagonists. Diego Noguera as Julio and Natalia Galgani as Emilia are fabulous.

For all its profundity, there are delightful moments of humour, especially when the students socialise. Some of the choice phrases at a home-party include, ‘I learn Latin better with beer in my corpus.’ A girl, perhaps Emilia, laments that for all the beer she’s downed she’s still stone sober, only to discover that it’s non-alcoholic. Another scene has Julio reading Swann’s Way on the beach. He falls asleep with the book open on his chest, which results in an odd book-stencilled sun-tan.

Eight years on, in the film’s present, Emilia has all but disappeared and Julio is a struggling writer. He accepts a job typing up a novel by the well-known author Gazmuri. He’s not yet started before he’s replaced by a cheaper secretary and is too embarrassed to admit this turn of events to his neighbour, Blanca. Blanca is a translator, whom he beds with far less passion than he had for Emilia.

Julio begins to write a novel in long-hand, adding the occasional coffee stain for authenticity, as he passes it off as Gazmuri’s. Through the book which Blanca helps transcribe, it would seem that the ‘author’ is still heart-broken. The viewer realises it is an outpouring of memories of Emilia, many of which revolve around bed and books such as Madame Bovary and A Remembrance of Things Past.

Blanca, meanwhile, perhaps inspired to find her true love and realising that she’s not Julio’s, decides to move on and does – to Spain.

Having now managed to lose his life’s second-most meaningful relationship, Julio turns to looking after a bonsai almost as therapy, and compares this painstaking activity to writing a novel. The bonsai itself also seems to mirror his love life in its slow and uneven growth. If only he’d applied the same care to making his relationships succeed or maybe he had and stunted the one he had with Emilia. Does this experience account for his indifference towards Blanca? Will his bonsai survive?

Jimenez has said that the film pays tribute to lies, fiction and the artificial and that it is full of jokes and music. Did Blanca realise Julio was lying about working for Gazmuri at any point and did Emilia lie when she said she’d read Proust?

Jimenez hadn’t always counted on being a novelist, having toyed with the ambition of being a comedian. He certainly sounds as though he’d be convivial company.