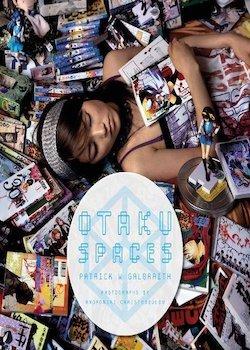

Otaku Spaces

By Patrick Galbraith, photographs by Androniki Christodoulou

Chin Music Press, Seattle, 2012

240 pages, ISBN 9780984457656

Review by Lucy Searles

For many, even for the Japanese themselves, the concept of the ‘otaku’ is still something misunderstood and often, misrepresented. Despite a number of academic works being produced on the idea; works that seek to define who otaku are, their consuming habits and the reasons for their interests, the ‘otaku’ still remains a mystery and a source of fascination for many in the west and in Japan. Otaku Spaces is a book that attempts to dispel some of these misconceptions by, rather than seeking to define what an otaku is, allowing these people who are considered to have otaku interests, to discuss their hobbies and the rationale behind them. In many of the interviews, for example the interview with the ‘race queen’ and model Mariru Harida, the idea of an otaku as an anti-social and unfashionable person is totally dispelled – while her interests are reading manga and collecting the related paraphernalia, the woman goes against the very definition of Otaku that is explained as the stereotype in the book’s introduction.

Galbraith begins by detailing the emergence of the concept of an otaku – describing them as someone (while there are female otaku’s, it is something that is generally associated with males) who devotes their life to anime, manga and games, who shuns work and responsibilities and spends huge amounts of money collecting and obsessing on their hobbies. The book then goes to describe the origins of the word and its use in Japanese society, briefly touching on the spread of the ‘otaku’ concept into the west. While this is important background information, it is not an exhaustive study of the otaku, and while a lot more could be offered on the topic the purpose of the book is not for Galbraith to explain his theories on what the Otaku is, but rather to allow for the people themselves to help explain what being an otaku is to them. The book then moves onto the most interesting section – the interviews and a look into the private spaces of the otaku.

While the interviews do demonstrate the expected otaku images, the girlfriendless men who have hundreds of figurines of scantily clad teenage girls and the infamous ‘hugging pillows’ that display young anime women, they also offer some surprising insights. For example the interview with Ryosuke Watanabe, who collects banned materials – from Aum memorabilia to Japanese bike gang stickers and KKK badges, comes as an interesting contrast with the anime obsessed interviewees later in the book, yet he expresses similar affections for his collection as the others do – statements that confirm the otaku stereotypes Galbraith describes in the introduction.

An interesting twist to the interview sections is the inclusion of the interviews with academics on the subject, but also the interview with western otaku and Internet celebrity Danny Choo. Choo, who himself writes on the subject of the otaku on his website dannychoo.com from a personal perspective, offers an insight into otaku culture as a western outsider who became interested in anime and manga, and whose interview is entertaining and insightful.

Galbraith then discusses the public spaces of the otaku, outlining the various Mecca across Japan that cater exclusively to the diverse tastes of the nation’s otaku consumers. The vivid descriptions serve more as a travel guide than offering an in depth history, with the exception of the section on Akihabara, but by describing the public spaces of the otaku, Galbraith is able to explain not only the growth of otaku culture, but to show how it is steadily becoming a more recognized sub-culture within Japan.

A highlight of Otaku Spaces is, of course, the beautiful photographs that the book contains. From the brightly coloured images of the rooms of the interviewees, surrounded by their interests and hobbies to the wonderfully rich photographs of stores, cosplaying teenagers and busy city scenes. A particularly wonderful image is the photograph of the cosplaying teenagers at Nippombashi’s Street Festa, where the vibrant anime characters stand out against the drab hustle and bustle of the city behind them. The photographs, which come courtesy of the Tokyo-based photographer Androniki Christodoulou, take the book from being simply an academic analysis of the space of ‘otaku-ness’ to being a wonderful celebration of it and widening the general appeal of the book from a niche interest into something anyone interested in Japanese culture and photography can access.

Galbraith has a brilliant knowledge on the subculture of the otaku, and Otaku Spacesis a wonderful starting point for anyone interested in this area of Japanese culture, whether it be academically or just from a personal interest. The book is well referenced, providing plenty of food for thought and opportunities to pursue reading on the topic, and the abundant photographs throughout the book put a face to the interviewees – offering an even clearer peek into the personal lives of this misunderstood group.