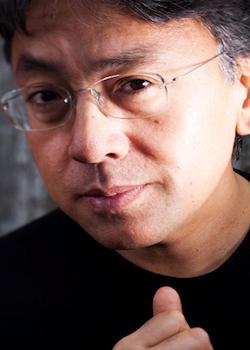

In Conversation with Kazuo Ishiguro

The Man Booker at Birkbeck

7 November 2012

Review by Susan Meehan

What an extraordinary event – Birkbeck’s Russell Celyn Jones, Professor of Creative Writing and former Man Booker judge, was in conversation with Kazuo Ishiguro in a large theatre at the Friends’ House and all for free.

The Booker Foundation and Man Group are collaborating with Birkbeck, University of London, to celebrate recent winners of the Man Booker Prize through a series of conversations with them – you can see the programme here

Kazuo Ishiguro was born in Japan and came over to leafy Surrey from Nagasaki when he was five years old. His parents expected to stay in England for only a year or two. Rather than integrating into British life, the couple would observe their neighbours’ behaviour and comment on how interesting all this was. Ishiguro admitted that this probably had the effect of allowing a young Kazuo to see Britain from an anthropological point of view.

Last time I heard Kazuo Ishiguro was at the Purcell Room, Southbank Centre in 2002. On that occasion Ishiguro went to great pains to dissociate himself from Japan. He emphasized to the audience that he could not read or write Japanese. He mentioned how in the 1990s he used to be asked to take part in television discussions for instance, to comment on the trade wars with Japan and to give his take on other Japan-related issues. Realising that he was not a spokesman for Japan, he deemed it best to begin declining these invitations.

Ishiguro’s books, which had started off with Japanese themes, also began veering away. He went on to portray an English butler, a European musician, a detective trying to solve the case of his parents’ disappearance in Honk Kong and, more recently, a group of friends who meet at a secluded English school called Hailsham.

At the Purcell Room talk in 2002, a woman asked Ishiguro how, as a Japanese man, he had been able to write about an English butler, to which Ishiguro, normally unflappable, visibly flinched and reminded her that he had lived in England since the age of five.

At the Man Book event at Birkbeck on 7 November, in conversation with Professor Russell Celyn Jones, Ishiguro seemed to have become reconciled to his Japanese heritage. It was a privilege to hear him at this free and well-attended event at the Friends House on Euston Road.

Kazuo Ishiguro, or Ish, as he was called by Professor Jones, won the Booker Prize in 1989 for his book, Remains of the Day. Three of his other novels have made it to the shortlist, When We Were Orphans (2000), An Artist of the Floating World (1986) and Never Let Me Go (2005).

The evening’s talk was mainly about Never Let Me Go but touched other aspects of Ishiguro’s style of writing. What was made patently clear throughout the dialogue, was Ishiguro’s tremendous humanity, empathy, honesty and reverence for human relationships.

The pair first looked at the naturalism in display in Never Let Me Go including references to Woolworths, an English seaside town and pubs in, ironically, a ‘counterfactual world inhabited by clones’ according to Jones. Though it is a novel rendered in simple language it is nevertheless other-worldly and Jones wondered where the voice came from.

Ishiguro said that Kathy H, the narrator, is something that he created and happened to use as the narrator. Ishiguro tends to audition different characters in his head for the role of narrator, behind which his own voice disappears.

While Jones admitted to feeling unsettled at not knowing were Ishiguro himself is in the book, Ishiguro said he doesn’t write as an alter ego. In fact, in his first novel, he took as narrator, someone as far removed from himself as possible – a Japanese woman in the latter stages of her life. Admittedly he is a little Japanese himself, he humourously admitted.

This distance allows Ishiguro to be less inhibited and allows him scope to figure out what to say which he wouldn’t be able to do otherwise.

Writing Never Let Me Go, Ishiguro pretended that the whole of England was like Norfolk on a grey afternoon, so all places described in the book, no matter where their location, would be described as flat and grey. He made sure to leave out anything that was colourful or exciting about England, bleaching out all colours.

Jones probed a bit more about Ishiguro’s Japanese family and voice. Ishiguro came over to Guildford when he was five. His father was an oceanographer and his parents expected to return home in a couple of years, but ended up staying on in England long-term.

Ish can understand Japanese women from the 1950s, thanks to having heard his mother talking Japanese when he was growing up, and tends to be able to understand 1950s women in Japanese films, while is completely thrown by the language used in samurai films.

The voice in his first novel, referred to above, was of an ageing Japanese woman, undemonstrative and elliptical. This voice has stayed with him through force of habit, he said, and is not artistically justified.

Jones brought up the theme often used by Ishiguro of unreliable memory against the backdrop of politics, be it World War Two or Japanese fascism, and wanted to further explore this. Ishiguro explained that well-meaning people may not have the perspective of the time they are living in. Ultimately, things they were most proud of may become what makes them most embarrassed in later life. Ishiguro wondered how his generation would react if found in that situation.

It is this idea of self-deception which fascinates Ishiguro, as well as the battle that we face between wanting to remember yet at the same time not wanting to remember. Nations go through this as well, which Ishiguro also finds compelling. Most countries have dark periods that they want or need to confront, but find it difficult.

Celyn Jones quoted JG Ballard who said, ‘The world is governed by fictions and it is up to authors to find reality.’

Jones asked Ishiguro what it is that makes us humans in the novel, wondering whether it is art that can be produced as evidence of our souls.

Ishiguro surprised me with his response which I found poignantly democratic and inclusive, by saying that art is a consolation and not ‘a big deal.’ Ishiguro said he is interested in all endeavours to make our lives meaningful and it could be our involvement in politics or menial work we do. Ishiguro sees people as having the determination to say we’ve done something well and finds this aspect of humans very moving. Even a burglar will want to execute his theft well.

This moral urge is what makes humans very different and special. It doesn’t have to be achieved through artistic endeavour. There is a lot of dignity in striving to do things well, not least in how people deal with their family and friends.

I was extremely touched by this compassionate take on life and surprised as some of his novels are about musicians and artists, and in Never Let Me Go there is a sense that artistic talent and achievement is a reflection of the soul.

Jones returned to the notion of Japan in Ishiguro’s work and wondered how his career would progress, reminding us that his first three books had been about Japan, and that Ishiguro has something that has always intrigued writers, a confluence between East and West.

As a teenager Ishiguro said he wanted to be a singer/songwriter in the mould of Bob Dylan or Leonard Cohen. He would go to open mics [a live show where audience members may perform at the microphone] and folk clubs. His songwriting was his apprenticeship in writing fiction.

When he was 21-22 he went through a Japanese phase. Up until then he felt that Japan was secure in his head but at 21 realised that Japan was not there for him any longer, and that it had changed. His Japan was his world of childhood. When a child moves home, there is an incentive to remember and, furthermore, his memories of Japan were nourished by parcels he was sent, full of comics and toys. His Japan was a rather precious place as he was growing up – it contained his best-loved toys and his grandparents, and was not a world that he could revisit on a plane.

In his early twenties, he felt he had to preserve this world which no longer had a physical presence and that is why he came to write about it. Up until that age, he had never been an avid reader and had no ambition to be a writer until that age. To help with his project he consumed lots of Japanese films from the late 1950s and early 1960s to remind him of Japan as it was at the time he’d left.

Ishiguro felt he had fulfilled his Japanese project, which coincided with him realising that he could not act as a spokesman for Japan.

Jones wondered what Ishiguro thought of the film adaptations of his books, Remains of the Day and Never Let Me Go.

Ishiguro claimed to love both films and said he’d acted as a kind of consultant on for both. While he has written screenplays, Ishiguro said he would never write a screenplay of one of his own books.

Ishiguro feels there is a strong alliance between literary fiction and high-end films. He said that high culture, by what he means more thoughtful literature, for example, is fighting an increasingly hard battle to remain relevant. The fact that a lot of recent good films have been adaptations of thoughtful books is very positive and Ishiguro said he is very glad that the film industry is paying attention to books.

Responding to a question at the end of his conversation, Ishiguro revealed that each novel hasn’t necessarily changed him as a person as had been anticipated by the questioner. As he writes very slowly, he wondered how much change was merely the fact that five years had elapsed during the writing of a book! He also said that while it would be easier if he could stick to one method of writing, it changes each time. Sometimes he plans a novel, on other occasions he won’t. The creative process just keeps changing.

In reply to a question about his living across cultures, he admitted to not being able to compare his childhood and background to anything else and is aware of other authors who can cross cultures equally well without having had his kind of background. His parents didn’t live like immigrants in Guildford as they thought they would return to Japan any day. Ishiguro saw them observe British culture through the eyes of Japanese people with a deep interest in England but without the feeling of investment towards a life in Surrey. It made him aware of rules and regulations in and differences between both cultures, resulting in a tendency to look at things through an anthropological lens.

Another question centred on the character of Ruth in Never Let Me Go who the questioner regarded as deceitful and problematic, leading her to ask Ishiguro how difficult she was to write as a character.

Ishiguro said he doesn’t think of his characters much in isolation. He tends to focus on how relationships and characters evolve from this. Ruth, he admitted, is most flawed as a human being but fundamentally decent. When her time is running out, Ruth goes about putting things right and fixing whatever had gone wrong in her relationships. For this reason Ishiguro sees her as a positive and affirmative character not concerned about wealth or selfish things at the end but about relationships. At heart, humans really care about friendship and love.

Ishiguro sees Never Let Me Go as his most cheerful novel, much to the amusement of his audience. He explained that the backdrop is sad but that the story is not about flaws and that all the characters are decent.

And on this note, this most thoughtful, magnanimous and humane of individuals got ready to sign books for a long queue of fans.