Aesthetic Strategies of the Floating World

Aesthetic Strategies of the Floating World, Mitate, Yatsushi and Fûryû in Early Modern Japanese Popular Culture

By Alfred Haft

Brill, Leiden and Boston, 2013, volume 9 in the series Japanese Visual Culture

216 pages, including endnotes, list of characters, bibliography and index

ISBN 978-90-04-200987-9

Review by Sir Hugh Cortazzi

Alfred Haft works at the British Museum as a project curator in the Japanese section of the department of Asia. He is also a research associate of the Sainsbury Institute for the Study of Japanese Arts and Cultures (SISJAC) at Norwich. This book is based on his Ph.D thesis and inevitably is more likely to be of interest to the specialist art historian than the general reader, but the book, which is copiously illustrated with reproductions of relevant Japanese prints in full colour, nevertheless has much to offer to anyone interested in the art and culture of the Edo period.

It is not possible in a brief review to give an adequate summary of Haft’s scholarly analysis of the three terms in the title to his book. But readers will note that in his introduction he explains that his study is largely built round the concepts behind the term gazoku which may be translated as the refined and the mundane. In the concluding section he sums up the terms mitate as “analogical juxtaposition,” yatsushi as casual adaptation and fûryû as standards of style, although such simplified translations fail to convey the complexity and nuances of these terms.

In chapter 1 he brings out some of the implications of the term yatsushi in the Edo period. It was for instance used for a man of higher social status who had come down in the world. He “endured his reduced circumstances in an easy going manner and eventually met with a happy end [p.39].”

He notes that one version of mitate involved the bundling of “elements of the everyday world (household objects) into an organizational relationship modelled on a component of high culture (nature studies)” i.e the combination of high and low culture.

Fûryû was “the ideal of elegance,” which is such an important element in so much of Japanese culture, but as Haft points out the term came in the eighteenth century to be used as a euphemism for kõshoku or eroticism. Prostitution was a major element of the floating world. It was, he notes “running rampant near the entrance gates to Edo’s many shrines and temples, and even on properties allotted for use by the shogun’s own retainers [p.29].”

In discussing the use of these terms in the Edo period Haft looks at the Japanese pastime of writing linked verses and haikai. For the haikai poet mitate denotes “the juxtaposition of two objects viewed to have a similar shape [page 91].” This leads him into a discussion of humour in Japanese poetry and art. He notes that the “culture of Edo Japan was alive with humor [sic], adaption, appropriation, innovation, unexpected juxtaposition, classicism, didacticism and continuity – a diversity of approaches spurring artistic growth in an ambitious range of directions [p.173].”

Haft’s book sheds much interesting light on life in the Edo period. The samurai were the elite but the ‘floating world’ was as much their world as it was that of the merchants and commoners. Actors may have been in theory outcasts but they were depicted by artists such as Shunsho Katsukawa [勝川 春章] in refined actor portraits such as the following:

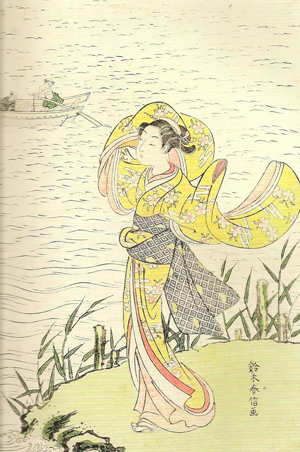

Haft’s chapter 4 entitled “Harunobu’s Textual Pictures” is a stimulating introduction to the colour prints of this outstanding artist. If I had to choose one Harunobu Suzuki [鈴木 春信] print from this book it would be the following print from the Honolulu Academy of Arts in which a young woman wears a robe with dangling sleeves, As Haft notes “Her slender form is characteristic of feminine beauty in ukiyo-e produced during the late 1750s-60s”: