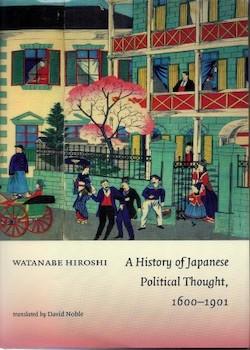

A History of Japanese Political Thought, 1600-1901

By Watanabe Hiroshi

Translated by David Noble

I-House Press, International House of Japan, 2012

543 pages including notes, bibliography and index

ISBN 978-4-903452-24-1

Review by Sir Hugh Cortazzi

Professor Hiroshi Watanabe is professor emeritus at the University of Tokyo and a specialist in the history of Japanese and Asian political thought. Students of Japanese history, philosophy and politics will find this book of outstanding value. It is clear, well-constructed and informative. The translation by David Noble reads well; indeed it rarely seems like a translation.

Professor Watanabe begins with a summary of Confucian thought and much of the book is devoted to an analysis of the various interpretations of Confucian precepts made by Japanese scholars in the Edo period including Hakuseki Arai [新井 白石], Sorai Ogyû [荻生 徂徠] and Shõeki Andõ [安藤 昌益].

Confucianism was not a religion, but was regarded as the official philosophy of the ruling elite. Confucian teaching, however, did not always conform to the realities of Tokugawa rule. The Confucian concept of meritocracy which lay behind the Chinese selection of bureaucrats through competitive examinations was at odds with the Tokugawa system where ‘the army was the bureaucracy, the bureaucracy, the army.’ The army consisted of the samurai who were an hereditary elite whose ‘stock in trade was the violence, maiming, and slaughter demanded by warfare.’ [pp 27-28] ‘The looting and pillage…often associated with the warrior class’ were hard to reconcile with the benevolence (jin -仁) of Confucianism. The ‘way of the warrior’ (bushi -武士道) as it developed in the peace enacted by the Tokugawa, which was ‘based on a very personal sense of honor and shame’ was ‘reduced to little more than sham and playacting’ [p.38].

Tokugawa rule was accepted for over 250 years if only because peace and civil order were preserved and there was no recurrence of the decades of terror that had prevailed before Tokugawa hegemony was achieved. But if the Tokugawa had received ‘the mandate of heaven’ should this mandate be preserved for ever? The Confucian precept of dynastic overthrow or hõbaku seemed sound to Ieyasu who usurped power, but ‘began to seem disruptive and traitorous in a world at peace’ [p.99]. Confucian precepts could thus be used against the maintenance of Tokugawa rule.

Confucianism was not the only philosophy which potentially undermined the shogunate. The researches and teaching of Mabuchi Kamo [賀茂 真淵] and above all of Norinaga Motoori [本居 宣長] on Japan’s ancient texts also challenged Confucian philosophy and undermined the basis of Tokugawa rule. Norinaga thought that ‘the ancient way’ signified ‘the great and honourable customs of our august land’ before they were polluted by the importation of teachings from the Asian continent [p.238].’ Norinaga believed that ‘the emperor rules not by virtue, but by heredity. Therefore, his sovereignty is absolute’ [p.245].

Another force for change was the perception which developed in the Edo period of Japan as an entity or country. As Japan became more prosperous under the pax Tokugawa, travel increased and there was increased demand for maps not only of Japan but of the rest of the world. Rangaku (Dutch studies) led to more information becoming available about the world outside Japan. By the middle of the nineteenth century it was apparent to many in Japan that the land of the rising sun could no longer remain isolated from the rest of the world. The idea that Japan was opened in one fell swoop by the force of Perry’s Black ships is a oversimplified myth. The time was ripe for change.

Watanabe has much else of interest to say about the Edo era and its codes and beliefs. His chapter sixteen on ‘Sexuality and the social order’ underlines the differences between China and Japan in relation to the role of women. Men and women mixed much more freely in Japan. Women ‘were expected to join men in performing quite arduous outdoor labor’ and women could and did participate in commerce [p.296]. Virginity was not a prerequisite for marriage. Women were expected to exercise their charms whether they were wives or courtesans or as Watanabe puts it ‘Ordinary women were courtesans in plain dress, courtesans were gaudier and more gorgeous wives’ [p.304]. The section of this chapter on homosexuality ends with this comment: ‘Homosexuality was an emblem of the misogyny arising out of the solidarity and machismo of the warrior class, as well as a symbolic expression of warrior rule in the realm of gender relations’ [p. 309].

Coming to the Meiji period Watanabe notes that ‘It was commonly (though tacitly) understood that restoring imperial rule did not actually mean reinstating personal rule by the emperor.’ He also points out that the Meiji leaders were frequently inconsistent in their beliefs and actions, ‘Many underwent multiple conversions’ [p.355], but this should not be held against them. Pragmatism was justified. He stresses that the Meiji state was not ‘a simple fusion of Western institutions of representative government with the ‘traditional’ Japanese emperor system.’ Indeed ‘the emperor system was modelled in certain respects on the monarchies of the contemporary West’ [p.389].

In the context of the Meiji Revolution (he prefers this to Meiji Restoration) he discusses in some detail the writing on political issues of Yukichi Fukuzawa who saw freedom as ‘liberation from a hereditary caste system.’ For Fukuzawa ‘the purpose of government is to guarantee order and advance the welfare and happiness of the people.’ Watanabe comments that Fukuzawa’s political philosophy at times ‘seemed a cynical pragmatism, at others lukewarm compromise, at others an effectively restrained idealism.’

Watanabe’s book explodes various historical myths and contains much food for thought. I commend it to all students of Japanese history and politics.