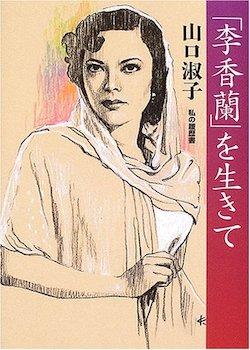

My Life as Li Xianglan

By Yamaguchi Yoshiko

Nihon Keizai Shimbun (2004)

Review by Fumiko Halloran

Yamaguchi Yoshiko was a prominent movie star and singer from the late 1930’s to 1958 when she married a Japanese diplomat and retired from a successful but controversial career. She was popular not only in Japan but in China, Hong Kong, and Hollywood.

The dramatic life she describes in this memoir illustrates the fate of a beautiful and talented girl who grew up in Manchuria when Japan established a puppet state there in 1932. Fluent in Mandarin and trained by a Russian opera singer, Yamaguchi lived a complicated life with several identities. This memoir illustrates the difficulties of living in a cross cultural environment that is exacerbated by civil turmoil and international conflict.

Born in 1920 to Japanese parents who lived in Fushun, Manchuria, her name was Yamaguchi Yoshiko according to her family’s registry in Saga Prefecture, Japan. Then, in accord with a Chinese tradition, she had two Chinese adoptive fathers, both of whom were close friends of her father, Yamaguchi Fumio. From them, she was given two Chinese names, Li Xianglan as the adopted daughter of General Li Jichun, and Pan Shuhua as politician Pan Yugui’s adopted daughter.

When she appeared in movies, she played the roles of Chinese girls or women and spoke only Mandarin. Millions of Chinese fans believed her to be Chinese until after World War II. She was put on trial by Chinese military authorities who accused her of betraying China to spy for Japan. She was found not guilty, however, after she proved that she was in fact Japanese. She escaped execution and was expelled from China.

Returning to Japan in 1946, she resumed her film career and married an internationally known artist Noguchi Isamu. Five years later they were divorced. She went to New York in 1956 to star in the Broadway musical “Shangri La” under the stage name of Shirley Yamaguchi. There she met Otaka Hiroshi, a young diplomat eight years younger, while she was performing in that musical. After they married two years later, Yamaguchi chose the name Otaka Yoshiko and retired from films and stage. Her husband later served as ambassador to Sri Lanka and Myanmar. She used her Otaka name when she ran for and was elected to the House of Councilors in 1974. She served in the parliament for eighteen years as a member of the Liberal Democratic Party.

Over the years in China, Japan, and America, she had five names with different identities. She suffered from emotional conflicts, according to this memoir, particularly as Li Xianglan, the Chinese star, which hid her true identity as a Japanese. As she rose toward stardom, Yamaguchi seemed unaware of the complicated political situation around her. She was keenly aware, however, of the Japanese military’s attitude toward the Chinese and was hurt by both Japanese mistreatment of Chinese and the hostility of the Chinese toward Japanese. When she went to Japan for the first time when she was eighteen years old, she was shocked by Japanese contempt and condescension toward Chinese even though her singing of Chinese songs was popular.

During the year Yamaguchi was born, Mao Zedong was a young man organizing a socialist youth group, the League of Nations was established, and California passed legislation that was seen as an “anti-Japan law” intended to limit Japanese immigration. In Europe, Mussolini grabbed political power in Italy and Hitler launched the first uprising in Munich, which failed.

As she grew to be a teenager in Manchuria and later Beijing, the Chinese fight against the Japanese was complicated by the civil war between the Kuomintang and the Chinese Communist Party. The Yamaguchi family’s Chinese friends were pro-Japan leaders who cooperated with the Japanese government and military while fighting the Chinese communists. Yet her best friend, a Russian girl with whom she maintained a lifelong friendship, turned out to have a father who was a Soviet Communist Party member working for Pravda and Tass, the Soviet publications.

Yamaguchi as Li Xianlang was named Japan’s Manchurian Goodwill Ambassador as she was propelled to stardom with movies including “Leaving a Good Name for Posterity” about the Opium War. It was produced in Shanghai by a joint venture between Japanese and Chinese as Japanese propaganda. The head of the production company, Kawakita Nagamasa, was a veteran in the film industry and chose themes that passed Japanese military censorship but appealed to Chinese audiences. In this movie, the Chinese understood that British colonial ambitions in China had been parallel to modern Japanese ambitions. General Lin Zexu who fought against British was a national hero. Li Xianglan appeared as a girl selling candy in the opium dens.

Yamaguchi recalls a painful press conference in Beijing shortly after the movie was released. A Chinese journalist accused her of appearing in movies like “Song of the White Orchid” “China Nights” and “Vow in the Desert” in which Chinese women were mistreated by Japanese men but then they fell in love with them. A journalist asked: “Where is your pride as a Chinese?” Yamaguchi writes that she almost confessed that she was Japanese. But the pressure on her not to disclose her true identity had been applied by different interest groups who had used her for political purposes. She apologized to the journalists and pledged not to be involved in such movies again.

She writes movingly about her visits to war zones in 1942. At that time she was working on an epic movie, “The Yellow River,” which took place near the frontline in Henan Province. Financed by the Manchurian Film Association, it was almost all a Chinese production. During the filming, the cast was in danger of being caught in the cross fire between the Japanese army and the Kuomintang or Communist Chinese forces. The theme was village life near the river in a place about to become a battlefield. When the production completed its work and left, Yamaguchi recalls that two extra train cars connected to theirs were filled with wounded Japanese soldiers covered with blood. Yamaguchi and another actress helped the medics attend to the wounded throughout the night. When the train stopped, even the dying soldiers wanted her to sing, so she jumped off the train and stood in a wheat field under the moonlight and sang old Japanese songs for the soldiers.

Having gone through pain of conflict between the Chinese and Japanese, and carrying a sense of guilt that her work as actress and singer had supported Japan’s behavior toward China, Yamaguchi watched from Tokyo the signing ceremony in Beijing establishing diplomatic relations between Japan and the Peoples Republic of China in the fall of 1972-and cried. Today she calls China her fatherland and Japan as motherland and has a simple message: “Stop war.”