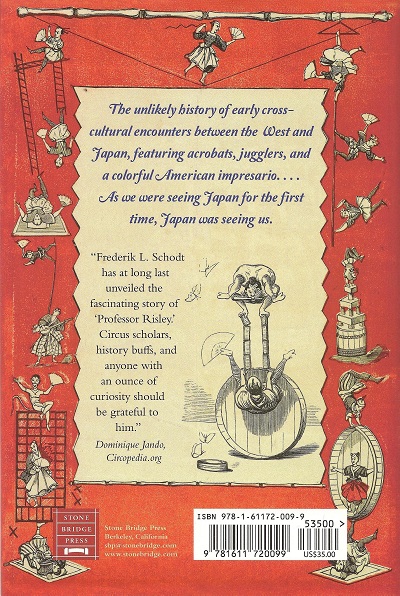

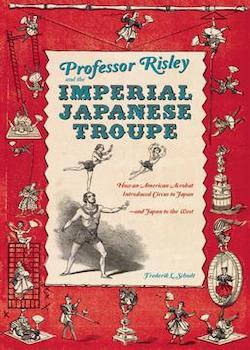

Professor Risley and the Imperial Japanese Troupe

By Frederik l. Schodt

Stonebridge Press, Berkeley, California

2012, 304 pages including notes, bibliography and index, numerous illustrations in black and white plus section of colour plates

ISBN 978-1-61172-009-9

Review by Sir Hugh Cortazzi

Frederik L. Schodt, who has written other books about popular Japanese culture, gives a colourful account of the life and travels of Richard Risley Carlisle, who used the stage name of Professor Risley, although he had no connections with any university and the title of professor was not conferred by any academic institution. He was born around 1814 in New Jersey. He became associated with the circus and the theatre and quickly became prominent as an acrobat performing feats including throwing off his feet, extended above him, his son into the air, who after a summersault landed on his father’s upturned feet.

Schodt follows Risley’s travels to the western United States, Europe and Australasia, Hong Kong and Shanghai. On 6 March 1864 Risley reached Yokohama accompanied by an equestrian troupe of ten performers and eight horses. On 28 March the first western style circus opened in Yokohama. As Schodt explains: “Audiences in the small Yokohama settlement were limited, with the special permission of naval captains Risley was able to expand his reach by staging performances for the sailors of the British fleet in port.” But “after a month or so, Risley’s circus ran out of steam.” Yokohama was too small and most of his performers left him. He managed to recruit an Australian friend and his wife but could not continue to keep up his circus. Instead he used his entrepreneurial spirit to set up an ice importing concern and later went into the dairy business, but this failed. His real metier was show business.

He saw that the traditional Japanese misemono (spectacles), kyokugei and kanawaza (acrobatics) which Japanese were beginning to despise would greatly appeal to western audiences and he began to assemble a troupe of top Japanese performers. He needed financial backing and joined with three others in concluding a contractual agreement on 1 November 1866 before the US consul in Yokohama. One of his partners was Edward Banks, who had been US Marshal in Yokohama and spoke some Japanese. They managed to get the necessary Japanese passports for their group. This was quite a feat as these were the first passports given to private Japanese citizens.

Schodt follows Risley and his troupe to the United States and on to Europe where they went first to Paris for performances to coincide with the 1867 Paris exposition. In Paris their audience included the young Tokugawa Akitake who was representing his uncle, the last of the Tokugawa Shoguns, at the exposition. Their acts included the butterfly trick, top spinning, rope dancing, ladder acts and various other acrobatic feats. In London they ran into some competition from another Japanese troupe known as the Gensui troupe who reached London before them.

The Japanese attracted a lot of attention especially when they wore Japanese clothing. Western languages and customs seemed strange to them and their belongings were sometimes stolen or lost in fires. They and Risley were occasionally involved in disputes which came to court. The members of the troupe did not bring their wives and often visited prostitutes.

After two years abroad and visits to Spain and Portugal, eight members of the troupe returned to Japan. Nine remained with Risley in the US and revisited Britain where they again ran into competition from the ‘Royal Tycoon’ group led by Tannakker Buhicroson whose ‘Japanese Village’ in Knightsbridge was the main theme in my book Japan in Late Victorian London: The Japanese Village in Knightsbridge and the Mikado, 1885 (SISJAC, Norwich, 2009 – and reviewed in issue 23, November 2009). The group gradually parted company. Risley returned to the United States and was eventually committed to a lunatic asylum where he died in May 1874.

Schodt’s book is based on meticulous research and his account of Risley’s life and of Japanese acrobats and entertainers in the US and Europe in the late 1860s will fascinate readers interested in the spread of Japanese popular culture abroad.