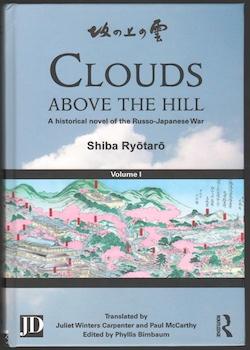

Clouds above the Hill

By Shiba Ryōtarō (司馬遼太郎)

Translated by Juliet Winters Carpenter and Paul McCarthy

Routledge, 2013

Volume I – 388 pages

ISBN 978-0415508766

Volume II – 399 pages

ISBN 978-0415508841

Review by Mark Headley

Shiba Ryōtarō, born in Osaka in 1923, studied Mongolian at the Osaka School of Foreign Languages and worked as a reporter in Kyoto. After the war, he began writing historical novels, mainly set in the Late Tokugawa and Meiji Eras, but also including works on Yoshitsune, Toyotomi Hideoyoshi and Tokugawa Ieyasu. Many of his novels have been adapted for TV and the cinema.

Clouds above the Hill, considered to be Shiba Ryōtarō’s most popular work, centres on the lives of two brothers, Akiyama Yoshifuru and Akiyama Saneyuki, and their friend, the poet Masaoka Shiki, all from Matsuyama (Shikoku), against the background of the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-95) and the Russo-Japanese War (1904-95). It originally appeared in a serial publication in eight parts from 1968 to 1972. The first four of these parts have now been published in an English translation in two volumes, and Volumes III and IV are due for publication in November 2013.

In both the First Sino-Japanese War and the Russo-Japanese War the newly industrialized Japan scored a spectacular victory over a far larger country in each case. In the former, although China had begun to modernize her forces, acquiring inter alia the German-built Dingyuan and Zhenyuan which were then amongst the most powerful battleships in the world and superior to any ships in the Imperial Japanese Navy, a large part of the funds allocated for this purpose were diverted by the Dowager Empress Cixi to such projects as the Summer Palace; in Ryōtarō’s words it ‘was, in short, something along the lines of a great experiment carried out between a superannuated order (Qing dynasty China) and a brand-new one (Japan)’ (Vol. I, page 260). The Japanese victory was a vindication of the Meiji policies of accelerated modernization over the preceding 25 years and Western armaments, training and tactics; the tremendous boost to their confidence allowed the Japanese to feel they had joined the ranks of the Western great powers, as shown by Japan’s alignment with the Western camp during the Boxer uprising of 1900, described in the book with particular reference to Japan and Russia (Vol. I, pages 370 to 375). That this equality with the Western powers was still something of an illusion was shown after the gains awarded to Japan in the Treaty of Shimonoseki were overturned by the intervention of France, Germany and Russia; it was Russia’s acquisition of these territories and, in particular her designs upon Korea, which led to the increase in tension between Russia and Japan which were ultimately to result in war.

The Russo-Japanese War was the first major war of the 20th century and is often considered to be the first ‘modern’ war. In many respects it was a precursor of the First World War ten years later. Although tanks, aircraft and poison gas were yet to be developed and the submarines already in service in the Russian and Japanese Navies did not play a decisive role, the heavy artillery, machine guns, trenches and barbed wire associated with WW1 were already present in the Russo-Japanese War.

In point of fact, however, Russia and Japan had one important feature in common: both were slow to adopt the modernization and industrialization of Western Europe, and later the USA, i.e. essentially Westernization. Amongst the numerous reformers, Peter the Great (1682-1725) single-handedly forced through a crash programme to turn Russia from a mediaeval backwater into a European great power; he succeeded in military terms by defeating Sweden and the Ottoman Empire, but social conditions, and in particular that of the serfs, remained largely unchanged. In the case of Japan, after the Meiji Restoration of 1868 it was eventually agreed to end the self-imposed isolation (sakoku) of two and a half centuries of under the Tokugawa Shoguns and to resist Western encroachment by adopting full-scale modernization, in order to avoid the fate of the Chinese who had revealed themselves powerless to resist Western aggression. Peter the Great’s attempts to modernize Russia were borne in mind by the Japanese, the book drawing an interesting parallel between him and the Japanese daimyō Shimazu Nariakira of Satsuma and Nabeshima Kansō of Saga who enthusiastically introduced new technology into their domains (Vol. I, page 351). Not only did Japan prove more successful than Russia in this respect, but it is probably universally regarded as the pre-eminent example of a successful newly industrialized nation.

At the outset of the war, Russia appeared to have the overwhelming advantage: with a population estimated at 130 million, Russia had an army of 1 million and, despite the conflict taking place at the other end of the Eurasian landmass from the political and industrial heartland, had the capacity to supply her forces by the recently completed Trans-Siberian Railway. Japan had a population of only around 46 million, and an army half the size of Russia’s. Russia’s Cossack cavalry was generally acknowledged to be the best in the world, whereas Japan’s was virtually non-existent. Russia’s attitude to Japan was generally one of overconfidence, grossly underestimating Japan’s potential.

That is not to suggest shortcomings in the Russian leadership. General Kuropatkin had visited Japan in 1903 and rated her army (but not the cavalry) and artillery as being the equal of their European equivalents; far from being an incompetent fool, he is described as ‘the finest tactician in Europe’ (Vol. II, page 267) and portrayed rather as too much of an absolutist, withdrawing from Liaoyang when the situation was less than perfect instead of taking the initiative when victory was still possible.

Conversely the Japanese leadership did not invariably display the degree of efficiency which one associates with Japan: the most prominent example of such failings is Major General Ijichi Kōsuke’s not seizing the unfortified 203-Metre Hill overlooking Port Arthur at the beginning of the siege. General Nogi Maresuke’s subsequent consignment of thousands of troops to their inevitable death in trying to capture it only after it had been heavily fortified is a recurrent theme of the book; Shiba is highly critical of Nogi, who has generally enjoyed the reputation of a war hero. Sadly, the degree to which blood was needlessly shed is perhaps the ultimate way in which the carnage of the WW1 was foreshadowed; in the author’s words (Vol. II, page 206) ‘The fort at Port Arthur became a vast pump that sucked up Japanese blood.’

The work is described as a ‘best-selling novel’, but in terms of depth and detail it goes way beyond even what is generally understood as being an historical novel. It is instructive to compare it with War and Peace which, despite Tolstoy’s own denial, may be taken as an archetypal example of such a novel. This is centred around a number of fictional characters against the background of Napoleon’s invasion of Russia; many of the protagonists, e.g. Prince Andrei, are directly involved in the action, and some non-fictional characters, e.g. Prince Speransky and Field Marshal Kutuzov, also appear. In the case of Clouds above the Hill on the other hand, all the characters are non-fictional; in this case the historical events are illustrated through the three central characters, in particular the Akiyama brothers. There is consequently a large cast of characters who serve as vehicles to advance the action; one surprising virtual absentee is the Meiji Emperor himself who puts in a minor appearance only late in Volume II.

In contrast to Tolstoy’s philosophizing, Clouds above the Hill is enlivened by frequent pithy observations, such as ‘The hardest part of foreign relations is the domestic rather than the foreign part.’ (Vol. II, page 44) or ‘The military profession justifies not just killing enemy soldiers but even more so, killing one’s own.’ (Vol. II, page 385).

Despite the wealth of detail the book contains, it is fast-paced and the momentum accelerates as the action progresses. As far as I can see, without reference to the original Japanese, the translation is also excellent.

As with any high-quality work, any errors, however minor, become more prominent by contrast with the remainder. I shall confine myself to mentioning the following: It was the English navy which defeated the Spanish Armada in 1588, not the British, as this was well before the Acts of Union of 1707 and indeed the Union of the Crowns of 1603 (Vol. I, page 307). The Spanish form of Christopher Columbus is Cristóbal Colón, not Cristóbol Colón. Vladivostok is better translated as ‘Rule the East’ (the usual rendering) or even ‘Control the East’ rather than ‘Conquer the East’, which is quite wrong and gives a misleading impression. Finally I am somewhat puzzled by the statement (Vol. II, page 304) that Napoleon received no formal training, i.e. military, when in fact he attended the military academy at Brienne-le-Château from 1779 to 1784 after which he trained in the École Militaire in Paris, graduating in 1785.

Clouds above the Hill will be essential reading for anyone with an interest in Japanese history, in Russian history and in the history of the 20th century in general. Readers of Volumes I and II will doubtless look forward to the publication of Volumes III and IV in November with the keenest anticipation.