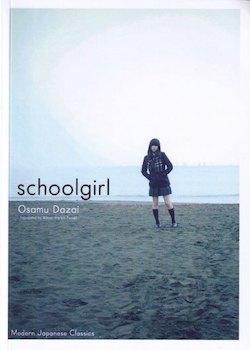

Schoolgirl

By Osamu Dazai

translated by Allison Markin Powell

One Peace Books (Paperback)

2012, 103 pages

ISBN: 978-1935548089

Review by Chris Corker

It isn’t always necessary to know the background of an author to enjoy a novel, but it often adds a depth and understanding that is otherwise impossible. This is certainly the case with Dazai [太宰 治 – 19 June 1909 to 13 June 1948], who in many ways epitomises the feelings of his contemporaries, and the younger generation of his time. Some authors steadfastly attempt to write what they don’t know; to experiment. Others rely on their knowledge and feelings to write what inevitably becomes a genuine representation of their thoughts and feelings. The latter is certainly true with Dazai, whose works all seem to be semi-autobiographical in nature, even (as is the case with Schoolgirl -女生徒) when the protagonist of the story is a young girl.

Schoolgirl was the first of Dazai’s published works, and gained him national acclaim. The novella is set in Tokyo during the Second World War, a time of patriotism and strife for the general population. Although, the protagonist seems unaffected by both. When being lectured at school, she notes the following:

‘She (the teacher) went on and on, explaining to us about patriotism, but wasn’t that pretty obvious? I mean, everyone loves the place they were born. I felt bored.’

To describe the plot in any depth would be an exercise in futility, as the novella takes the form of a day-in-the-life, stream of consciousness, similar to an extended diary entry, where the young protagonist begins by talking about certain events that have influenced her life such as the war and the death of her father, only to then be sidetracked on some minor detail and to go off on a tangent, giving us a glimpse into her psyche.

It’s obvious that the protagonist is a person, much like Dazai, who is struggling with their role in their particular class. Dazai, who felt great resentment for the ease of his life and the luxury of his social status, was never on good terms with his parents, or in many cases his siblings. He was even a member of the Japanese communist party, whose ideal would certainly see Dazai’s class dragged from their pedestal. These acts of self-flagellation were a constant feature in Dazai’s years and he finally succumbed to them in 1948, when he committed suicide after several unsuccessful attempts.

The girl in the story seems to be in the same state of conflict as Dazai, not only with her class but also with her emotions, which are so often juxtaposed with how she is supposed to behave. During the course of the story, she struggles to adopt these affectations that more often than not represent the polar opposite of how she really feels. Like Dazai, she believes privilege to be a curse:

‘…before I knew it that privilege of mine had disappeared and, stripped bare, I was absolutely awful.’

She is also in a constant state of self-analysis, where every action that she considered a failing is logged and serves as source of shame. Even as her train seat by the door is unashamedly taken from her by a man (an action that is still easy to witness in modern Tokyo), the protagonist, after pointing out his impropriety, still manages to allot some of the blame to herself:

‘When I thought about it, though, which one of us was the brazen one? Probably me.’

The novella is a form that hasn’t enjoyed the same success in the west as it has in Japan. There is no escaping the fact that this book is very short, despite the inclusion of a preface and a foreword, which are themselves quite brief. Standing at just over 100 pages, and with a third of each page illustrated with the kanji for the title of the book, it could be argued that it isn’t the best value for money. I would say that the strength of this medium, and indeed the strength of Dazai’s works, is that this brevity facilitates a large amount of imagery in each page. Every paragraph that you read and every page you turn has you thinking back, considering the subtext and significance of seemingly throwaway comments.

If one part of the book could sum up the sentiment and the feeling of Dazai’s works in general, it would be this, the imagery and word use being deep but accessible:

‘(Waking up in the morning is) Sort of like opening a box, only to find another box inside, so you open that other box and there’s another box inside, and you open it, and one after another there are smaller boxes inside each other, so you keep opening them, seven or eight of them, until finally what’s left in the box is a small die, so you gently pry it open to find…nothing, it’s empty.’

A note on the translation. While I think that Allison Markin Powell has done a great job of recreating the voice of a teenage girl, readers from the United Kingdom may find the Americanisms such as ‘bogus’ and ‘the worst’ to be irksome. Otherwise, this is a crisp and accessible translation.

I would recommend readers who have enjoyed this book to try No Longer Human (Ningen Shikkaku –人間失格) as it feels like a much more fleshed-out version of Schoolgirl, and one that seems to represent Dazai’s feelings even more overtly. There are few works of supposed fiction that could claim to be more autobiographical in nature. Fans of the confessional style of Dazai and Japanese literature may also want to try Mishima’s Confessions of a Mask, a brutally honest but beautifully written look into the life of another of Japan’s famous authors.