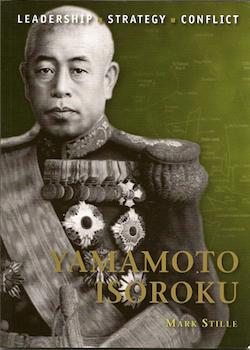

Yamamoto Isoroku: Leadership, Strategy, Conflict

By Mark Stille

illustrated by Adam Hook

Osprey Publishing, Oxford

2012, 64 pages

ISBN: 9781849087315

Review by Sir Hugh Cortazzi

Mark Stille was a Commander in the US Navy and has worked in intelligence for over 30 years. He has written widely about naval history in the Pacific. This slim volume provides an introduction to the life and strategy of one of the leading Japanese naval commanders in the Pacific War. Isoroku Yamamoto [山本 五十六] is supposed by many to have opposed war with the United States. Yet he ‘personally advocated the attack [on Pearl Harbor] and went to great extremes to execute it, in spite of almost universal opposition within the Imperial Japanese Navy.’ Stille points out that Yamamoto was not opposed to war with the United States as such but only to a drawn out conflict which Yamamoto recognized Japan could not win. The surprise attack which Yamamoto devised was ultimately disastrous for Japan as it galvanized the Americans ‘with a thirst for revenge and an unwillingness to negotiate anything short of total victory, thus removing any hope of a peace favourable to Japan.’

Stille explains that initial Japanese naval victories in the Pacific war were more due to ineffective and limited Allied resistance than to the skill of Yamamoto. In his view Yamamoto’s ‘faulty planning and poor execution resulted in a seminal defeat’ at the battle of Midway which was the only occasion on which Yamamoto took a fleet to sea under his direct command.

Yamamoto, who graduated from the naval academy at Etajima in 1904, was badly wounded while serving on board a Japanese cruiser at the Japanese victory at the battle of Tsushima in May 1905. He recovered and was duly promoted after staff college and service at sea to Lieutenant Commander. In 1919 he began one of his first tours of duty in the United States where he studied English intensively. In 1923, because of his knowledge of English, he accompanied the Navy Vice Minister on a tour of the USA and Europe. He served again in the US as an attaché from 1926-28 and in 1930 he was appointed assistant to the Japanese delegation to the London naval Conference. Yamamoto had therefore plenty of international experience. He was also well informed about naval aviation as in 1924 he had been assigned to the Kasumigaura Aviation Corps where he worked hard to master aviation technology.

In the years leading up to the Pacific war Yamamoto and other senior naval officers worked hard ‘to curb the influence of the Army and stop the march to war.’ Following the conclusion of the German non-aggression pact with the Soviet Union in August 1939 Yamamoto who had become Naval Vice-Minister was forced to resign from this post but was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Combined Fleet despite the fact that he ‘had had little command experience.’

Stille gives a clear account of the way in which Yamamoto forced through ‘his vision’ of an attack on Pearl Harbor which he hoped would break American morale. In fact its effects were the opposite of that intended. If Japan had limited itself to attacking the British and the Dutch in South East Asia it would have been difficult for Roosevelt to declare war on Japan and American isolationism could have revived.

Stille gives an interesting analysis the battles of the Coral Sea and Midway and discusses Yamamoto’s role in the Guadalcanal campaign. He also describes how Yamamoto came to his death when the aircraft in which he was flying was ambushed by American fighters.

Japanese intelligence was frequently poor. In the naval battles in the Pacific in which Yamamoto was involved he ‘possessed almost no credible intelligence and filled in the gaps with a series of incorrect assumptions.’

Stille’s assessment of Yamamoto is that while he possessed charisma and was far-sighted he was not a military genius. He hated pomposity, but could be sentimental. He could also be hard if not brutal, but was an inspirational leader. He was ‘a womanizer who largely ignored his family.” He was a gambler in his personal life and ‘This trait carried over into his professional life.’

Stille’s assessment may not accord with Japanese views of their naval hero, but anyone interested in the history of the Pacific War will find this brief study thought provoking.