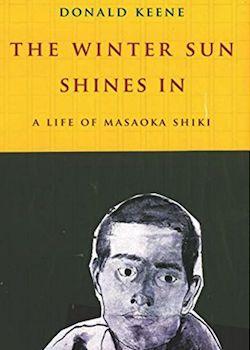

The Winter Sun Shines In, A Life of Masaoka Shiki

By Professor Donald Keene

Columbia University Press

1 Aug. 2013, 192 pages

ISBN-10: 0231164882

Review by Sir Hugh Cortazzi

Professor Donald Keene, who is now a Japanese national and lives in Tokyo, is the doyen of western studies of Japanese culture and history. He began to study the Japanese language more than seventy years ago and has written some thirty scholarly and very readable studies of a wide variety of aspects of Japanese culture, in particular Japanese literature through the ages.

His latest book describes the life and works of one of the most significant poets of the Meiji period, when Japanese literature in response to the revolutionary changes then taking place in Japan adopted new forms and styles.

Shiki Masaoka [正岡 子規] is best known as the leading haiku poet of the modern era, but he also, as Keene explains, wrote tanka, modern poems (shintaishi), novels and essays as well as a Noh play. His life was a short one (1867-1902) and for much of it he suffered from debilitating and painful ailments.

Keene gives an interesting and informative account of Shiki’s life and the many literary figures including the novelist Natsume Soseki with whom Shike came in contact during his brief life.

Shiki was born in Matsuyama in Shikoku. He was the son of an impoverished low ranking samurai. He was ambitious and in 1883 made his way from Shikoku by sea to Tokyo where he began to study philosophy, but he was temperamentally unsuited to the subject and soon turned to literature and aesthetics. He forced himself to overcome his physical weakness and became intrigued by baseball. The following haiku composed by Shiki in 1890 reflects his enjoyment of the game:

harukaze ya

mare no nagetaki

kusa no hara

Spring breezes –

How I’d love to throw a ball

Over a grassy field.

He took up journalism and determined to become a writer. Despite the handicap imposed by illness he acted as a war correspondent in the Sino-Japanese war of 1894-5 for the nationalist newspaper Nippon. He was highly critical of the way in which the Japanese army treated war correspondents as equivalent to private soldiers. But his primary interest was literature.

Shiki founded the haiku journal Hototogisu whose creed was shasei which meant that haiku must reflect real life rather than the idealized world. Haiku “must include the ordinary and even ugly elements of daily life.” Keene in his introduction quotes the following haiku written by Shiki in 1896 as an example of shasei:

aki kaze ni

koborete akashi

kamigakiko

As it spills over

In the autumn breeze, how red it looks-

My tooth powder

The first haiku by Shiki which was printed was, Keene notes in discussing Shiki’s student days, the following:

mushi no ne wo

fumiwake yuku ya

no no komichi

Trampling through

Insect cries, I create

A path through the fields

Among haiku by Shiki, quoted by Keene, the following ‘is notable not only for its sensitivity to nature and the seasons, typical of Japanese poetry, but also for its unusual combination of imagery’:

ajisai ya

kabe no kuzure wo

shibuku ame

Hydrangeas –

and rain beating down

on a crumbled wall

Shiki criticized what he considered the excessive reverence for the haiku master Matsuo Basho (1644-1694) and praised the haiku of that other master of haiku the poet and painter Yosa (Taniguchi) Buson (1716-1783) whose haiku had, Shiki thought, been neglected. Shiki attracted a number of disciples including another famous modern writer of haiku Kyoshi Takahama [高浜 虚子] although he and Shiki did not always agree. Basho, Buson, Issa and Shiki (and perhaps Kyoshi) are now seen by many as the leading Japanese haiku poets.

Keene ends his introduction to this biography with the following conclusion about Shiki’s contribution to modern Japanese literature: ‘The haiku and tanka were all but dead when Shiki began to write his poetry and criticism. The best poets of the time had lost interest in short poems. Shiki and his disciples, finding new possibilities of expression within the traditional forms, preserved them. The millions of Japanese (and many non-Japanese) who compose haiku and tanka today belong to the School of Shiki, and even poets who write entirely different forms of poetry have learned from him. He was the founder of truly modern Japanese poetry.’

We must hope that Donald Keene continues for many years to add to his many books on Japanese culture.