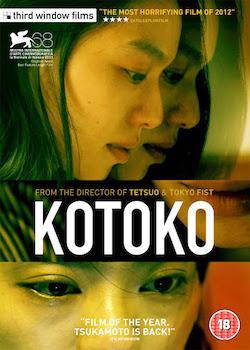

Kotoko

Produced, directed and starring Shinya Tsukamoto (塚本 晋也)

2011, 91 minutes

Currently out on release on DVD

Review by Mike Sullivan

Shinya Tsukamoto has been in film making for many years and is well known for his horror movies, as well as movies that explore a transformative form of rage. His work nearly always features people who struggle to maintain their sanity with endings that are normally destructive. Violence is often an aspect of his movies; however it is violence which is consistent with the horror genre, while other films focus more on the violence of the mind. For example, in Body Hammer a man’s anger turns him into a human weapon while in A Snake of June a wife is blackmailed to do things she doesn’t want to do while increasingly her husband begins to enjoy the blackmail more than the guy doing it. In other words, when going to see a Tsukamoto movie one has to be prepared for unsettling scenes, mental turmoil and destructive violence. Kotoko was not only directed by Tsukamoto, it was written and produced by him, and in line with previous movies he also stars in the movie.

The main character of the movie, Kotoko, is played by Cocco (真喜志 智子). A singer for many years, this is the first time she has acted in a movie. In the last decade she has released albums, art books, written for newspapers and published a novel. For this movie she not only starred as the leading lady but was also responsible for the art direction and music. It was a brave decision to take on this film role as she is the protagonist and portrays a a character suffering from mental instability. However, this was a role she knew inside and out because she wrote the original story from which Tsukamoto created the screenplay. It becomes clear in the movie that both Tsukamoto and Cocco have a shared vision.

The premise of the movie takes on a subject which is taboo in Japan, mental illness, and presents the plight of a single mother trying to raise a baby while suffering from her own personal demons. The movie raises a lot of questions, not only about how people with mental illness perceive the world, but how Japanese society perceives them, and how this can make things significantly worse. At the 68th Venice International Film Festival, Kotoko won the Best Film Award in the Orrizonti section, showcasing new trends in world cinema, becoming the first Japanese movie to win the award.

The vast majority of the movie is entirely focused on Kotoko, she lives alone with her baby while working full-time. However, as the movie opens it quickly becomes clear that she doesn’t perceive the world in the same way others do. In particular everyone appears to be two people to her, one is normal and the other is someone who wants to hurt her. One of the first scenes is perhaps representative of the whole movie. While working in a store, to her right side we see a father with his son, browsing the aisle, while to her left side the father appears again just standing, staring at her menacingly. Suddenly the threatening version of the man runs at her with a clear intent to attack and she hides her head in her arms in fright. When she looks again there is no one there, just the father with his son still preoccupied with browsing. In this way we can see that she fears both men and society. A common theme of the film is the way people just stare at her as if she is not real. In particular, whether because of past trauma or something else, she greatly fears violence. The other aspect of the store confrontation is that, if she is not threatened, Kotoko simply finds herself ignored. Every day, once home, Kotoko cuts her skin to prove to herself that she still exists.

The one stable person around her is her son who she truly loves; when she is with him she seems to retain a small grasp of reality yet at the same time the fear inside her reaches new levels. She is not only scared of what people can do to him; she is also scared of what she could do. As an indication of the severe stress she is under, when Kotoko holds the baby she constantly reminds herself to clasp him securely, fearing that she might drop him. When she is outside she has to face two demons, the fear of others who appear in double form and the fear of anything happening to her child. When she imagines that a scary double is going to attack her baby she reacts violently, and subsequently has to move home. This appears to be a common occurrence yet at no point do we see help of any kind being offered. Despite her repeat attacks on others we never see the involvement of the police or a sign of anyone intervening. The overall picture is of isolation. On one occasion she hallucinates that she has dropped her baby off the roof and runs down screaming to the ground floor. Although Kotoko narrates how she had to apologise to all her neighbours and we hear the sound of sirens, we see neither paramedics nor police and the neighbours themselves are absent. They all remain faceless, invisible and unaccountable.

Eventually the combination of everything that is happening to Kotoko reaches a point where people can’t ignore it anymore and the baby is taken away to be given to her sister’s care. We are given the impression that if she gets better then she can get her baby back, yet she doesn’t appear to receive any support. We glimpse one short meeting with an unknown official telling her that it is common sense for a mother not to harm a child. This short scene demonstrates a very big gulf between what is actually happening, a single mother struggling with mental illness, and what the authorities perceive to be happening, a mother not taking proper care of her child. It becomes clear that she is on her own to ‘get better,’ while her sister’s family appear to be kind to her and caring for her child. However, there is no discussion with her family about what is wrong with Kotoko or how to help her. It becomes another big silence in the movie – the family seem to just accept that she is who she is, but ignore the underlying problem.