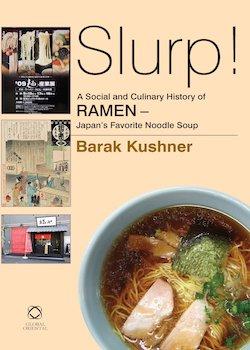

Slurp! A Social and Culinary History of Ramen – Japan’s Favorite Noodle Soup

By Barak Kushner

Global Oriental, Leiden-Boston

2012, 289 pages including index and bibliography, numerous illustrations

ISBN 978-90-04-21845-1

Review by Sir Hugh Cortazzi

Under the heading ‘Ramen is Japan’ Barak Kushner asserts: ‘Ramen (regular and instant) permeates all features of contemporary Japanese life.’ He goes on to declare that a life-style investigation in 2004 showed that an overwhelming majority of Japanese prefer ramen to other noodle dishes including soba, udon or pasta. As someone who is particularly fond of zaru-soba and who is conscious of the pride of various regions such as Nagano in their own special varieties of soba and udon, I find this surprising.

Barak Kushner, who teaches modern Japanese history at Cambridge University, is a ramen enthusiast who clearly enjoyed greatly doing the research needed for this fascinating book. In delving into the history of ramen Kushner throws light on many interesting aspects of Japanese social and political history as well as on Japan’s lengthy and complex relationship with China.

‘Where did ramen originate?’ He asks. When he put this question to Osaki Hiroshi who established the Ramen Data Bank, the answer began: ‘Ramen represents Japanese culture in that the main pillars of its origin are Chinese but later, Japan nurtured these elements for itself and created something completely different from Chinese culture.’ This is true of many other aspects of Japanese culture.

In his further investigations Kushner tries to discover the origins of the term ‘ramen’ and notes that before the Pacific War peddlers with their food carts used to call their noodles Shina soba (Chinese soba). One theory is that the word ‘ramen’ came to be used because Japanese cannot pronounce the consonant L, which was used in la-mian, the Chinese term for pulled noodles.

One important post-war development was the invention of instant ramen by Momofuku Andô [安藤 百福] who apparently found how to develop the product by looking at how tempura is made. ‘The trick is to fry the noodles quickly enough and in hot enough oil that they fuse into a hard block.’ Kushner declares that ‘Instant ramen helped to spur Japan’s third food revolution.’ Instant ramen is one of Japan’s contributions to the world’s inventory of convenience foods.

What is the difference between washoku and Nihon ryôri? Kushner explains that washoku is used to describe traditional home-grown cuisine while Nihon ryôri includes dishes imported from abroad and adapted to Japanese taste. Tempura and sukiyaki fit into this category. Washoku reflects the austerity, which Japanese had to endure because of the vagaries of the Japanese climate and the unsuitability of much of Japan’s terrain to agriculture.

Among the interesting historical facts, which emerge in Kushner’s survey of Japanese food culture, are his comments on the Heian court. The members of the court produced fine literature and poetry, but their quality of life ‘was less than brilliant. They gorged on rice with a few pickled side dishes and rarely exercised…The men drank large quantities of a sweet alcoholic drink and developed a range of diabetic-related illnesses.’

A modern Japanese would have found Japanese food and cuisine in all periods up to that of the Tokugawa shoguns almost unbelievably poor. No meat, limited vegetables and fish unless you lived by the sea. Rice was a luxury. Millet, which was turned into soba, was the staple diet. In the war years and after even the sweet potato Satsuma-imo was a luxury.

Buddhist precepts forbade the killing of animals. Fish were not ‘killed;’ they died from being brought out of their natural watery environment. The casuistry, which allowed such an exception, led in Tokugawa times to inoshishi (wild boar) being referred to as yama-kujira, mountain whales!

Kushner has also much of interest to say about the role of food in Shinto and in the ritual of Japanese life.

I would have welcomed a comparison between the spread of ramen culture with the development and role of pasta in Italian cuisine and its spread through Europe and North America, but this would perhaps have made the book too weighty a tome.

I also missed any reference to Morioka’s wanko-soba. How many cups could Kushner manage to consume?

Japanese food in recent years has become hugely popular in western countries. Paris has even more Japanese restaurants than London. Sushi, once regarded as ‘yuk’ is now the luncheon choice of many western office workers. Kushner’s book should ensure that ramen becomes equally popular.

This is a book, which anyone interested in Japanese food, will enjoy. I hope that hotel book-shops in Japan will make sure that they have copies on their shelves for visitors as well as for foreign residents.