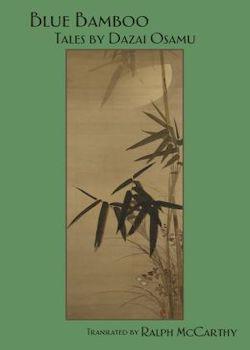

Blue Bamboo

By Dazai Osamu

Translated by Ralph McCarthy

Kurodahan Press

25 december 2012, 220 Pages

ISBN: 490207558X

Review by Chris Corker

This collection of short stories, released recently through the still relatively young Kurodhahan Press, can be seen as a quaint but pleasant divergence from the narrative and themes that fans of Dazai will be familiar with. While readers of the previously released Crackling Mountain and Other Stories may find something familiar here (as with Crackling Mountain there is another retelling of a story by Ihara Saikaku), others will no doubt be pleasantly surprised by the whimsical tone and light-hearted humour of the stories contained.

First, a note on the presentation. The cover is pleasantly subtle – and of course very Japanese – and the matte finish of the cover combined with the thickness of the pages are a nice change from the mass-produced, glossy paperbacks that are so common nowadays. In a market where effort only seems to be taken with hardbacks, it’s nice to own a paperback that doesn’t leave you feeling as though you have purchased something that is best disposed of after reading, before it falls apart of its own volition.

At the start of this collection is a foreword by the translator, Ralph McCarthy. Set in a familiar and easy-to-read tone, this section is used to give a little background to the stories, as well as explaining his reasoning for including each. While not overly long, I found this section answered most of the questions I might have had after reading. It was also refreshingly honest about some of the short-comings of certain stories, despite his obvious fondness for others. The translation itself is very clear and straightforward, suffering from none of the awkward structure and bizarre phrasing that used to plague translated works.

On Love and Beauty and Lanterns of Romance are both stories that are centred on a particular family. In a mirror of Dazai’s own childhood (it’s interesting to note that the father figure in these stories is dead, while Dazai was never on good terms with his own father), the family are rather well-to-do and their main challenge in life seems to be their struggle with an ever-encroaching boredom. In order to combat this they gather to pool their imaginative resources and create a story. Through this narrative, each of the characters’ personality traits, desires and fears are revealed as they present themselves bare and vicariously through their protagonist. I would agree with the translator when he says that he would have liked to have seen more of this household in further stories. It’s a shame that they only get these two brief outings.

The next two stories, The Chrysanthemum Spirit and The Samurai and the Mermaid, deal with man’s pride, obstinacy and the Samurai notion of honour. These themes are shown later in the book, but nowhere are they as pronounced as they are here. The Chrysanthemum Spirit, which takes the form of a classic fairy tale, tells the story of a man who is so proud of his skills that he refuses to be helped by anyone else, while The Samurai and the Mermaid highlights the importance of honour to the Samurai. When Konnai is accused of lying about his defeat of a mermaid to his face, his need to prove his tale and clear his besmirched name consumes him. This story is enjoyable as, despite its serious and finally morbid tone, it retains the narrative drive of a fairy tale, always maintaining the importance of fantasy. This is highlighted in the following speech by a supporter of the protagonist:

‘To a true Samurai, trust is everything. He who will not believe without seeing is a pitiful excuse for a man. Without trust, how can one know what is real and what is not? Indeed, one may see and yet not believe – is this not the same as never seeing? Is not everything, then, no more than an immaterial dream?’

This line, rife with the Zen ideology that was utilised by the Samurai in their Bushido code is concluded with a phrase that the reader cannot help but see with a little irony.

‘…thus ends this story affirming certain victory for those with the power to believe.’

This line is brilliantly juxtaposed with the tone of the story, creating an unnerving climax that feels less like a true ending and more like the naive, wishful thinking of a child. Another inclusion that takes the form of a classic story, Romanesque, uses a more conventional approach to the telling of a fairy tale, but also ends in peculiar introspection that purposely betrays the conventions that have preceded it.

Blue Bamboo – despite its fantastical themes – and Alt Heidelberg, feel very autobiographical in nature. The first deals with a man who feels worthless no matter how much he drives up the determination to succeed, and is eventually tempted away from his unpleasant life by an implausible fantasy. The second is a good example of the classic nostalgic tale, where the rose tint falls away on a return to a favourite place of childhood. Both of these act as good insights into Dazai’s personal feelings and bear some resemblance to his better known works, such as No Longer Human and The Setting Sun.

While it may be difficult to find an obvious common theme among all of these stories, many of them contain Dazai’s idiosyncrasies and give insights into his own life. Some are undoubtedly weaker than the others but they are still, each of them, enjoyable on their own merits. There is nothing earth-shatteringly insightful here, but there is plenty of reticent philosophy and gentle adventure that can be enjoyed by all.

Learn more about the Kurodahan Press